Introduction

Civilizing Projects and the Reaction to Them

Around the geographic periphery of the Chinese empire, later the Republic of China, and now the People’s Republic of China, as well as in some of the less accessible parts of China’s interior, and sometimes even in its cities, live a variety of peoples of different origins, languages, ecological adaptations, and cultures.1 These peripheral peoples or, as they are now customarily tagged, “minorities,” have been subjected over the last few centuries to a series of attempts by dominant powers to transform them, to make them more like the transformers or, in the parlance of the transformers themselves, to “civilize” them.2 There have been at least four such civilizing projects in recent history, carried out by the three successive Chinese governments and by Western missionaries who operated in China between the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 and the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949. This book is concerned with the ideology of three of these projects and with the similarities and differences among them, as well as their effect on the peripheral peoples (particularly in the development of ethnic consciousness) and on the central, civilizing powers.

THE NATURE OF CIVILIZING PROJECTS

A civilizing project, as described in this book, is a kind of interaction between peoples, in which one group, the civilizing center, interacts with other groups (the peripheral peoples) in terms of a particular kind of inequality. In this interaction, the inequality between the civilizing center and the peripheral peoples has its ideological basis in the center’s claim to a superior degree of civilization, along with a commitment to raise the peripheral peoples’ civilization to the level of the center, or at least closer to that level. Simple relationships of military conquest and subsequent domination, such as that exercised by the Mexica (Aztecs) over conquered peoples elsewhere in Mesoamerica, or by the Romans over some of the provincial peoples in the Near East or northern Europe, are not at issue here, even though those relationships involve an ideological as well as a political and economic basis of domination. Rather, the civilizing center draws its ideological rationale from the belief that the process of domination is one of helping the dominated to attain or at least approach the superior cultural, religious, and moral qualities characteristic of the center itself.

As an interaction between peoples, a civilizing project requires two sets of actors, the center and the peripheral peoples; in no case can we understand the entire project by looking from the perspective of only one side. And as with any interaction between peoples, participation in the civilizing project affects the society, culture, morals, and religion of both the civilizers and the civilizees.

The effect of the civilizing project on the peripheral peoples varies not only with the success of the project (the degree to which they become “civilized”), but also with the degree and nature of their complicity in the project. As one possibility, we have the cases of conquered peoples resisting any attempt whatever to civilize them, so that government agents have had to resort to virtual kidnapping of Native American children to educate them in boarding schools (Sekaquaptewa and Udall 1969:90–93; Pratt 1964:202), or Ferdinand and Isabella deciding they had to forcibly prohibit all aspects of Islamic culture, from veiling to couscous, in the newly conquered territories of Granada after 1499. In the Chinese context, this may be most characteristic of the situation in Tibet, where Tibetan nationalists (who knows what percentage of the Tibetan population) reject all claims of the Chinese state to be raising the level of Tibetan anything, from philosophy to mortuary practices to land tenure systems.

MAP 1. China. Provinces and autonomous regions with large minority populations shown in GAPS.

At the other extreme, peripheral peoples become partly or wholly complicit in the civilizing project, often when their relationship of asserted cultural inferiority is balanced by superiority or equality on another plane, as when the Yaqui, recent victors over Spanish armies in the early seventeenth century, requested Catholic missionaries to instruct them in the true religion (Spicer 1988:4), or, in this book, the case of the Manchus, conquerors of China and emperors of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), selectively absorbing parts of Chinese culture while maintaining their position as rulers.

In between these extremes lie the majority of cases, in which peripheral peoples are concerned with maintaining their own identity, and thus resisting any implication that all aspects of their culture, religion, or morals are unequivocally inferior to those of the civilizing center, but nevertheless participate to some degree in the project of importing some elements from the center into their own culture and society. Most of the cases in this book, in which peripheral peoples acknowledge at least some aspects of central civilization to be desirable, fit into this intermediate category. In some such intermediate cases, however, the peripheral peoples, while resenting the attempts to civilize them, nevertheless accept the general premise that they are less civilized or morally less worthy. They thus develop a “stigmatized identity” (Eidheim 1969; Hsieh 1987), a sense of themselves as backward, uncivilized, dirty, stupid, and so forth.

In all these cases, the effect of a civilizing project seems to be to engender, develop, sharpen, or heighten the consciousness of the peripheral people as an ethnic group. In this sense, ethnogenesis can be seen primarily as the reaction (reaction, of course, is not so simple as just opposition or resistance) to a civilizing project.

At the same time, participation in a civilizing project also has an effect on the center. In the first place, certain dominant civilizations seem to have a greater propensity to engage in civilizing projects than do others; as a rough approximation Hindu and Buddhist civilizations, for example, seem to be less inclined toward such projects than their Christian, Muslim, or Confucian counterparts.3 But even those civilizations with an innate propensity toward undertaking civilizing missions are transformed by the nature of the actual missions they carry out.

For example, the civilizing center, in its formulation of its project, needs to develop formal knowledge of the other and of itself. The development of social evolutionary theory in the West in the nineteenth century by such authors as Morgan (1985 [1877]), Tylor (1871), and Spencer (1860) coincided rather neatly with the expansion of Western colonies into new parts of the world, inhabited by peoples with social and cultural structures that differed considerably from those of the center, and the adoption of a modified version of such theories by Marxist governments in the Soviet Union (Connor 1984) and China coincided with the attempt to turn what had previously been rather pluralistic empires into more unified nation-states. The Orientalism described by Edward Said (1979) is after all a scholarly component of a larger project by which the West aimed to civilize the Muslim world.

In addition, the civilizing center, through its project, almost always develops a more conscious and sharper image of itself, in contrast to its images of the periphery. The true religion is contrasted with the mistaken beliefs of the heathens, as Arthur Smith did over and over in comparing Confucianism to Christianity (1970 [1899]), or the European stage is seen as a higher stage, a culmination of a series of inferior steps, as in the social evolutionary formulations, or Confucianism defines itself as having culture (wenhua, lit. “literary transformation”) in contrast to the cultureless peoples of the periphery.

Looking at civilizing projects in this way, as asymmetrical dialogues between the center and the periphery, allows us to analyze the projects into two components: the ideological discourse of the center (to which the members of the peripheral peoples may subscribe or contribute in varying degree), and the ethnic discourse of the periphery. The center’s discourse is ideological in the narrow sense of justifying or legitimizing a particular power-holding institution (which, in this book, is either the Chinese state or the missionary wing of Western imperialism). The peripheral discourse is ethnic in the sense outlined below—the development of the consciousness that a people exists as an entity that differs from surrounding peoples.

THE IDEOLOGY OF THE CIVILIZERS

As with any ideology, the ideology of a civilizing center tailors itself to its goals, in this case the facilitation of the civilizing project through the creation of hegemony, a relationship of superiority and inferiority that maintains the hierarchy by justifying it through ideology and institutions, making it seem both proper and natural to both the rulers and the ruled (in this case the center and the periphery) and enlisting both rulers and the ruled in service of the institutions that maintain the order (Gramsci 1971 [1930s]:12–13; 55–564). Civilizers—at least those who have worked with the peripheral peoples of China—have based their attempts to establish hegemony on a particular formulation of the nature of ethnicity, many of whose characteristics recur from one project to the next.

The Hegemony of Definition

The first requirement for those who would civilize is to define, to objectify, the objects of their civilizing project (Said 1979:44–45). The definitions produced must consist of two parts: a demonstration that the peoples in question are indeed inferior, and thus in need of civilization, and a certification that they can in fact be improved, civilized, if they are subjected to the project. Such a definition process serves several functions: it establishes the assumptions and rules according to which the project is to be carried out; it notifies the peripheral peoples of their status in the system, and of why and how this requires that they be civilized; and, perhaps most importantly, it gives the imprimatur of science to what is essentially a political project.

All the civilizing projects described in this book have had the process of definition and objectification at their base. The Confucians, beginning with an assumption of hierarchy based on the moral values of “literary transformation,” set out to classify peoples as closer to or farther from the center on the basis of just how much wenhua they had. This both legitimized the superior status of the center (thus giving it a mandate to carry out the process) and determined the methods to be used in ruling over peoples, according to how close to civilization, and thus how civilizable, they were. In Southwest China most of the Miao, for example, as treated in Norma Diamond’s chapter, were seen as so distant from civilization as to be barely susceptible to rule, let alone transformation, while various peoples known as yi (a category not coextensive with the Yi

(a category not coextensive with the Yi treated in Stevan Harrell’s paper) were more civilized already, and thus susceptible to being brought yet closer to the ethics and culture of the center. The Manchus, who themselves as rulers controlled the process, were of course fully capable of absorbing, even improving upon, the literary, moral, and cultural accomplishments of Han civilization, even while they preserved and refined for themselves a separate, distinct identity (Crossley 1990a; Rigger, this volume).

treated in Stevan Harrell’s paper) were more civilized already, and thus susceptible to being brought yet closer to the ethics and culture of the center. The Manchus, who themselves as rulers controlled the process, were of course fully capable of absorbing, even improving upon, the literary, moral, and cultural accomplishments of Han civilization, even while they preserved and refined for themselves a separate, distinct identity (Crossley 1990a; Rigger, this volume).

In the missionary project, definition placed peripheral peoples along a series of axes, some of them technical-cultural (many peoples were beloved by missionaries for being simple, guileless, direct, and so forth, as indicated in Swain’s contribution here) and others religious, which at one level consisted simply of contrasting the heathen delusions of native religions with the revealed truth of Christianity, but at another attempted to certify the potential for Christianization (a version of civilization) by tracing links between the superficially superstitious beliefs of the natives and the traditions of monotheism.

The Communist project has been the most explicit and systematic in its process of definition. It has classified the population within China’s political borders into fifty-six minzu, or “nationalities,” so that every citizen of the People’s Republic is defined as belonging to a group that is more civilized or less so. This scaling of groups, in turn, is based on an avowedly scientific scale of material stages of social process (derived from Morgan and Engels, refined by Lenin and Stalin), that tells each group exactly how far it needs to go to catch up with the civilizers.

In every case, then, the process of definition is one of both objectification and scaling. And while the scales used by the various civilizers seem on the surface to be quite different from each other, they all have in common certain metaphors that lend force and coherence to the scale created. In particular, the metaphors of sex (peripheral peoples as women), of education (peripheral peoples as children), and of history (peripheral peoples as ancient) stand out as recurring themes in the definitional process.

The Sexual Metaphor: Peripheral Peoples as Women

Sexual relations, seen as a man doing something to a woman, are a pervasive metaphor for a variety of relations of domination in many cultures,5 but they are particularly noteworthy in the imagery of civilizing projects. This eroticization and feminization of the peripheral occurs at a series of levels and in a series of differing contexts.

At the simplest and most direct level, civilizers of all sorts have seen peripheral peoples as both erotic and promiscuous in their behavior, as being at a lower level of culture where they have not yet learned the proper civilized morals of sexual repression and/or hypocrisy. Since Chinese culture has strict rules of sexual propriety (as well as a long and honored tradition of sexual hypocrisy), both the Confucian and the Communist versions of the civilizing project have defined peripheral peoples as erotic and seen the imposition of proper sexual morals as an essential part of the process of civilizing. For example, as Diamond mentions here, “Miao albums,” which portrayed and classified the upland peoples of the Southwest in Ming (1368–1644) and Qing times, commented extensively on their loose sexual customs, and in addition often portrayed these people acting provocatively, immodestly, or as if they were about to engage in sexual relations. At the other end of our time scale, any researcher who has spent time in China has heard from Chinese colleagues of the sexual customs of certain peripheral peoples—the current favorite seems to be the “walking marriage” of the Mosuo people mentioned in Charles F. McKhann’s contribution here. I remember vividly my conversation in 1988 with a schoolmaster at a middle school that enrolled minority students in special classes. He was proud of his minzu ban, but confided that there were certain problems. For example, a boy and girl in one of the classes had fallen in love, and started going everywhere and doing everything together. Fortunately, teachers and counselors were able to educate them, to persuade them that this kind of behavior was no longer appropriate in a modern, socialist society, and the couple broke up.

Also at a rather direct level, civilizers have seen the peripheral peoples as objects of sexual desire. The long tradition of this in the colonizing Orientalist writers and artists such as Gauguin and Flaubert is well analyzed in Said’s now-canonical work (1979:190), and we all know of the tradition of Western sailors and native girls throughout the era of imperialist maritime expansion. But it also occurs specifically in China.

Most obviously, there is the portrayal of women of peripheral peoples in Han art and literature. Already mentioned are the scantily clad Miao women of the Ming-Qing pictorial albums, but there is also the “Yunnan school” of painting (McKhann n.d.), which consists primarily of portraits (some innocent enough, some verging on the sexually exploitative) of minority, never Han, women.6 Even in Sichuan, where the tradition is less well developed, some of the first paintings on nonrevolutionary themes that were exhibited in Chengdu in the late 1970s were portraits of pretty Tibetan women.7 They were in no sense erotic pictures, let alone pornographic, but it is significant that when the artist wanted to paint a young, desirable female, he portrayed a Tibetan, not a Han Chinese. And finally, there is the curious practice among Han tourists, reported here by McKhann, of using telephoto lenses to take surreptitious pictures of Dai women bathing in the Lancang (Mekong) River in the southern Yunnan prefecture of Xishuangbanna.

One might suggest that this erotic portrayal of women of the periphery is simply a response to the strict sexual morals of the Han, which have probably become less widely hypocritical since the overlay of Communist puritanism. It would simply be too scandalous to portray a Han woman in this way, but minority women, being less civilized (perhaps slightly less human?) are fairer game.8 This analysis is correct as far as it goes, but what it neglects are the consequences of this portrayal. These include the eroticization and feminization of minorities in general and denial, in a male-dominant society, of full male status to those whose cultures are of the periphery.

This point is reinforced by another and less directly erotic aspect of the metaphor of peripheral peoples as women: in fact the great majority of portrayals of non-Han peoples, whether in traditional albums or modern tourist guides, are pictures of women. For example, two sets of fifty-six collector’s cards each, one for each minzu in each set, include seventy-six that show only women or feature women, twenty-five that show only men or feature men, and eleven in which the sexes are relatively balanced. In each case, the women shown are invariably young and pretty; the only exception in the two sets of cards is a curious picture of a fat babushka in a dirty dress representing the Eluosi (Russian) minzu of Xinjiang. The men, where they are shown, are about equally divided between young and old.

Once again, an objection might be raised—it is the women, after all, who wear the fancy clothes, the “traditional ethnic costumes,” which may or may not have much past history (see Trevor-Roper 1983), so they are more interesting to show in pictures. Although this is undoubtedly true, it raises the further question of why the women have distinctive costumes while the men do not. It appears, at least tentatively, that the women are carriers of this tradition (both in the hegemonic ideology of the civilizers and in their own practice) precisely because women are thought to epitomize peripheral peoples, since peripheral peoples are in some sense feminine. It is perhaps also true that because women are less likely to participate in such concrete institutional aspects of the civilizing project as schools and local government, they are thought of as “more ethnic,” and thus more appropriately dressed in ethnic costumes.

There may be a parallel here between the construction of funü (women) as a category in the Communist ideology of women’s liberation and sexual equality (Barlow 1990) and the construction of shaoshu minzu (minorities) in the Communist ideology of nation-building and ethnic equality. In both cases, there is an objectification of a category that is peripheral (or, perhaps, in the linguistic sense, simply marked) with respect to the normal category of the civilizers, who are, in the first instance, male, and in the second, Han. As pointed out above, to stand up for the rights of a category, one must first define it. And because both minorities and women are subordinate categories under the tutelage of the state’s civilizing project, they are conflated at some level of the imagination. Minorities are like women, so women represent minorities.

Finally, we might mention that peripheral peoples, like women, are seen as polluting—both dirty and dangerous—at least in the ideologies of the China-centered projects. Women, of course, are seen as polluting in Chinese folk ideologies generally (Ahern 1975); menstruating women or those who have recently given birth are offensive to the gods of popular religion, and their presence or that of others who have recently had contact with them chases the gods away. This idea of pollution—dirt and danger—is also extended to minorities. Lack of sanitation is one of the points Han ethnologists almost always bring up when they are swapping stories about fieldwork in peripheral regions; I once heard an informal exposition on this point that began with “Each minzu has its own zangfa [way of being dirty] . . .” And Diamond has pointed out graphically that Miao people, particularly Miao women, have been thought by their Han neighbors to be especially adept in the art of poisoning by magical means (1988). In all these cases, the peripheral peoples are dangerous in the same ways women are dangerous: by their power to pollute.

At all these levels, then, the sexual metaphor is one of domination, in which the literal or figurative femaleness of the peripheral peoples is one aspect of the act of defining them as subordinate.

The Educational Metaphor: Peripheral Peoples as Children

As mentioned above, the definitional process has two elements: it not only demonstrates the inferiority of peripheral peoples, but also certifies their civilizability, and thus legitimates not just domination but the particular kind of domination we call a civilizing project. The sexual metaphor, powerful as it is, addresses only the first half of the definitional task; it demonstrates inferiority, but inferiority of the sort that cannot readily be corrected. If peripheral peoples were visualized according to the sexual metaphor only, this would present difficulties for the civilizing project. Seeing peripheral peoples as children, on the other hand, is potentially even more useful: since children are by definition both inferior and educable, the peripheral peoples represented as childlike are both inferior and civilizable, and it becomes the task of the center to civilize them.

Like the sexual metaphor, the educational metaphor operates on different levels. The first of these is a quite literal one: civilizers see their peripheral subjects as childlike. This is often the case with missionaries in various parts of the world. The comments of Catholic priests working among the Yanomamö (Chagnon 1983:196–98) and the Sani (Swain, this volume), as well as those of Protestants working among the Miao in Yunnan (Cheung, this volume), all attest to the simple nature, the lack of guile, and ingenuousness of peripheral peoples. As Margaret Byrne Swain points out here, Vial often referred to his Sani flock as “mes enfants.” And, like children, the objects of missionizing can be trained, educated out of their childlike state.9

But missionaries, who often refer to their subjects as children, are not the only ones who have viewed peripheral peoples in this way. Popular images of minority peoples in today’s People’s Republic also include childlike elements. Educators I have known who work with minority education often comment that minority students, while every bit as intelligent as the Han, nevertheless require a different approach; they are unacquainted with abstract or metaphorical thought, and need to have everything explained to them in literal detail. The toning-down of educational rigor reported by Wurlig Borchigud (this volume) also seems to stem from an idea of peripheral peoples as childlike.

On another level, the juvenile image of the peripheral is presented in official discourse in which the Han and minorities are described as xiongdi minzu, or big-brother/little-brother minzu, with the Han (the socially and economically more advanced group) representing the big brother. It is by following the previous example of the big brother that the little brothers can advance to the more developed state represented by the Han. When brothers grow up, of course, they are all adults, but then, in Chinese at least, an older brother is still an older brother. Here again, the idea is that the peripheral peoples are like children—inferior but potentially educable.

Finally, there is the rather more concrete level at which children represent to the civilizers the best hope for accomplishing the civilizing project. Missions almost everywhere have established schools, and China is no exception, for it is by educating the young minds—those not yet fully enculturated into the less civilized ways of the periphery—that the project can most effectively proceed. And as Borchigud so effectively shows in her contribution to this volume, minzu jiaoyu (ethnic education) serves the identical purpose for the Chinese government. Not only are peripheral peoples childlike, but actual children, like actual women, are in a way most representative of peripheral peoples.

The Historical Metaphor: Peripheral Peoples as Ancient

A third metaphor that is common to all the civilizing projects examined here stems from a potential contradiction in the civilizing ideology. If peripheral peoples are, as the project requires, both primitive and civilizable—that is, if the scalar differences between them and the civilizers are not permanent—then there must be some explanation for why the difference exists. Racial explanations, though often employed, heighten the paradox: if the scalar differences are really inborn, then there is a question of whether they can be overcome. The paradox is partially resolved, however, when the historical metaphor is employed. Peripheral peoples are ancient, unchanged, not so far along on the same scale as the people of the civilizing center. But if the ancestors of the center were once as primitive as the periphery is now, then the project of trying to civilize them has some chance of success.

We find in the particular civilizing projects studied here a recourse to historical formulations of the primitive that derive from a variety of historiographie traditions. For example, there is the matter of tying knots and notching sticks. As early as the Yi jing (Book of changes), Chinese historiographers have seen tying knots in strings as a sort of protowriting; the usual formulation is that a big knot stood for a big event, while a small knot recorded a lesser event. This seems to have been accepted as a common practice everywhere among preliterate peoples. It crops up in the descriptions of small, remote minzu even in reports from the 1950s. People who are in a “primitive” state, since they do not have writing, must have cord-knotting and stick-notching; this makes their primitiveness equivalent to that of ancient peoples, and makes them a survival of ancient times.

Western attempts to trace world historical migrations, from the seventeenth-century Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, who traced all learning, including ancient Chinese philosophy, back to Egyptian roots (Mungello 1985:134–73), through the Kulturkreislehrhe (Culture Area Theory) of Father Schmidt and his early twentieth-century Vienna School (Schmidt 1939), also served to place peripheral peoples somewhere way back in history. Perhaps the clearest example in this volume occurs in the attempts by French and German missionaries and explorers in the early twentieth century to sort out the origin and history of the various “races” of Southwest China. The autochthonous strain, the most primitive, was related to peoples of the Pacific, while the ancestors of the Liangshan Yi were seen as of Eurasian origin, and indeed as preserving many of the admirable qualities of the early nomadic peoples of biblical times (see Harrell, this volume). Contemporary peripheral peoples were seen as survivals of forms that had existed everywhere much earlier in history.

It remained, however, for the Communists to develop the historical metaphor to its fullest. Because they have adopted and developed the notion, systematized by Lewis Henry Morgan, that the development of human history proceeds everywhere in distinct stages, and that each of those stages consists of a complex of related culture traits, it follows that peoples who display certain sorts of culture traits must be representative of the particular stage in which those traits occur. Matriliny occurs, for example, as the second substage of the primitive stage, while certain kinds of metallurgy are characteristic of slave society. In this way, almost any difference between the center and the periphery can be readily translated into a historical gap between the way things are done now and the way they were done at the evolutionary stage represented by the peripheral people. Many examples could be cited, but perhaps the most telling is the famous statement, widely repeated not only in Chinese ethnology but in such unexpected places as English-language coffee-table books (Wong 1989:48) that the Mosuo people of Ninglang County, Yunnan, are “living fossils” because of their matrilineal household organization and their lack of formal marriage bonds (see McKhann, this volume).

Through pervasive metaphors of this sort, civilizing projects explain and legitimize themselves. By portraying peoples of the periphery as female, juvenile, and historical, the Han or European center, which is by implicit or explicit contrast male, adult, and modern, legitimately assumes the task of civilizing, and with it the superior political and moral position from which the civilizing project can be carried out.

In line with their various claims on moral and cultural superiority, the civilizing centers of all three projects discussed in this volume have seen their approach to China’s peripheral peoples as but part of a larger project that has also aimed to civilize that portion of the Chinese population that is less cultured than the center: the black-headed masses for the Confucians; all heathen Chinese (that is, all Chinese) for the Christians; and the uneducated or politically unaware masses for the Communists. From the reading of the Kangxi emperor’s sacred edict in the Qing dynasty marketplaces on market days (Hsiao 1960:185–205) to the Civilized Village Campaign of the 1980s (Anagnost n.d., ch. 3), Chinese governments have seen their own role as a civilizing one, and missionaries of course were interested in converting—civilizing—the Chinese in general. But the approach to the peripheral peoples is a more extreme form of the civilizing project, and for two reasons. First, the cultural distance between the civilizing center and the peripheral peoples is greater than that between the center and the Chinese masses. Second, the civilizing project engenders in the peripheral peoples a particular kind of reaction: the formation of ethnic consciousness. This is a paradoxical result; it tends to emphasize or re-emphasize the very difference between center and peripheral peoples that the civilizing project was ostensibly trying to reduce or eliminate. It is when directed at peripheral peoples that the civilizing project takes on its full and paradoxical character.

A SUCCESSION OF CIVILIZING PROJECTS

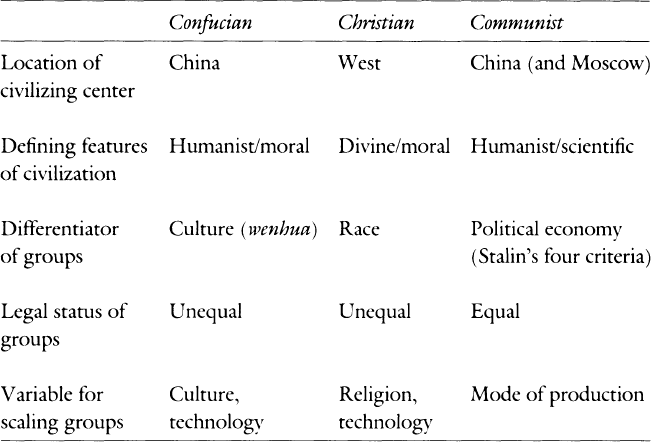

The successive civilizing projects that have approached the peripheral peoples of China have had much in common, as indicated in the above section, but they have also had their differences, and these differences have of course affected the ways in which the peripheral peoples have reacted. We can form a first impression of the most important individual characteristics of the Confucian, Christian, and Communist projects from the simple chart in table 1. Each project is conceived of as emanating from a particular center, as defining civilization (or the desired state) according to a certain set of philosophical principles, as separating groups according to some sort of criterion of “ethnic identification,” and then giving these groups equal or unequal legal status, while scaling them according to one or another variable.

TABLE 1

Comparison of Civilizing Projects

The Theory of the Confucian Project

To date, the Confucian project is the least well studied and thus least understood of the three. But that the attitude of the late Imperial (Ming and Qing) Chinese state toward its peripheral peoples can be characterized as a civilizing project, we have no doubt. From the standpoint of Confucian worldview, civilization was characterized by wenhua, which refers to the molding of the person (and by extension the community to which the person belongs) by training in the philosophical, moral, and ritual principles considered to constitute virtue (Schwartz 1959:52). It follows that there was a scale of civilizedness, with the most civilized being those who had the greatest acquaintance with the relevant literary works, namely the scholar-officials who served the imperial state and who served as theoreticians of the moral order. Other Chinese were somewhat cultured; their family life, religion, language, and other attributes were similar to those of the literati, even if they had no refinement or direct knowledge of the important literature. Non-Chinese were a step down, being not even indirectly acquainted with the moral principles laid out in the classics.

But what seems important here is that who was cultured and who was not depended not so much on race but on moral education, so that the process of acculturation was eminently possible. Peoples who had been beyond the pale of civilization could enter if they acquired the requisite knowledge and the proper modes of life. Hence Ming “ethnologists” were concerned not with race or language as determining characteristics of peoples, but with modes of livelihood; agriculturalists were more civilized than herders of the steppes (Crossley 1990b). Similarly, people whom we today might consider members of minority nationalities or ethnic groups—on the basis of their language, for example—were not excluded from participation in the bureaucracy or even in the examination system if they had acquired the requisite literary (that is, moral) knowledge.

This moral scale of peoples fits in nicely with the continuing historical process of absorption of once-peripheral peoples into the broader category of Zhongguo ren (people of the central country), or Chinese. We know that ever since the southward expansion of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), regions had been sinified by a combination of Chinese migration, intermarriage, and cultural assimilation of the former natives. And that process was legitimized by the ideology that it was behavior, rather than race, that determined civilization.

This does not mean, however, that at any particular time all peoples within sight of the Confucian center were considered equally capable of being civilized. As Diamond shows in this volume, peoples in the Southwest, for example, were readily divided into raw (sheng) and cooked (shu), according to whether they were cultured enough to accept moral edification and eventual civilization (in the case of the cooked peoples) or whether at present they were so wild and so far from the standards of civilization that they were fit for nothing but being controlled and perhaps painted in one of the famous “Miao albums.”10 A similar raw/cooked distinction was made until very recently when talking about the aborigines in Taiwan, and indeed the distinction has been borne out in practice: most lowland (shu) aborigines have lost records of their aboriginal status and have simply become Han Chinese. Upland (sheng) aborigines, on the other hand, maintain a separate ethnic identity even as the government attempts to assimilate them into the great Chinese nation (Hsieh Shih-chung 1994).

The most important thing to remember about the Confucian attitude toward peoples of the periphery, then, is that the center saw its relationship with the rest of the world as a process of making it more cultured, as a transformation from raw and untutored to fully civilized. The center believed so strongly in the moral rightness of this project that it tended to phrase all its accounts of its dealings with the outside in these terms. When the Qianlong emperor sent his famous letter to George III, expressing his gratitude that George had expressed “humble desire to partake of the benefits of our civilization” (Cameron 1970:313), he may or may not have believed that the British monarch was inspired by such a desire, but he was speaking the conventional language that stemmed from the presumed relation between the Chinese center and everyone else. In the case of the peripheral peoples, in many cases the emperor must have believed it; certainly the common people did and still do.

The Theory of the Christian Project

This project involved more than just the Christian conversion of China’s peoples. Particularly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with which the essays in this book are primarily concerned, the mission enterprise sought to bring not only the Gospel, but the modern life of Christian nations—with all its advantages in health, technology, and science—to the peoples of China (Smith 1970 [1899]; Hunter 1984 is a particularly revealing instance of this attitude on the part of American female Protestant missionaries). It is also important to remember that the Christian project, at least in its nineteenth- and twentieth-century versions, was closely connected to the project of Western imperial expansion generally. At the same time, the missionaries stand out from most traders and warriors, and many colonial administrators, in that the missionaries’ primary motivation lay in the civilizing project itself, whereas the primary motivations of their compatriots were often profits, markets, resources, and military strongholds. It would be inaccurate to call the whole colonial enterprise simply a civilizing project (though it did contain elements of one), but the missionary portion of the West’s nineteenth-century expansion can stand as one of the prototypes of a civilizing project.11

The Christian civilizing project was, of course, directed at various times and places toward the whole non-Christian world, and this included the Han as well as China’s peripheral peoples. But in many ways, the peripheral peoples provided more fertile ground than the Han on which to sow the seeds of the Gospel and modern life. This may well have been because many peripheral people saw the missionaries as a useful counterweight to the Han (see below), but for whatever reason, it meant that missionaries paid the peripheral peoples attention disproportionate to their numbers.

It is also, at times, difficult to separate the efforts of missionaries from those of other agents of Western imperialism in China, such as traders, explorers, and government representatives. This is particularly true for the definitional aspect of the civilizing project: Catholic missionaries such as Paul Vial (Swain, this volume) and his colleague Alfred Lietard, along with their Protestant counterparts such as Samuel Pollard (Diamond, Cheung, this volume) provided information that was used by explorers such as A.-F. Legendre (Harrell, this volume) and by stay-at-home scholars in Europe itself. Insofar as the missionaries provided accounts of the life of the peripheral peoples, they participated in the great scholarly enterprise that Said (1979) has characterized as Orientalism,12 as Swain points out in her contribution here. This involved defining and scaling groups, in this case identified primarily by race and presumed racial origins, along a scale that was both moral (Christianity providing the only true morality, but others possibly approaching the ideal more or less closely in the absence of revealed truth) and technological, with the advanced peoples of the Christian West demonstrating the overall superiority of Christian civilization. In a large number of cases, Vial’s included, the peripheral peoples fared rather better in the rankings than did the Han, especially in the moral ranking, where peripheral people’s honesty, simplicity, and hard work (or even their brave, martial nature, in the case of Egon von Eickstedt’s racial characterization of the Lolo [1944]), along with their failure to practice certain Chinese customs that the missionaries considered abhorrent (such as footbinding, infanticide, and arranged marriage), contrasted with the clever but sly, sneaky, and untrustworthy trading mentality of the Han.13

But missionaries themselves, of course, were interested not only in classifying and scaling the peripheral peoples; they also, more importantly, wanted to convert them. In converting their charges, the missionaries took their first step toward bringing them up to equality with the missionaries’ own civilizational standard. But in most cases, missionaries did not then feel that their work was done, or that the new Christians were really at the level of the old. People were still in need of tutelage before they could be independent in their new faith and whatever cultural and technological innovations it brought with it. Although by the time the missionaries were expelled from China between 1949 and 1951 many congregations had been turned over to peripheral peoples, they remained under the supervision of missionaries. Perhaps the reckoning was still to come; eventually, we may expect, the Christian congregations would have been given autonomy or would have demanded it for themselves. But by the time the Christian project was brought to an abrupt and involuntary end, its promise of fully civilized status for the peripheral peoples was yet to be realized.

The Theory of the Communist Project

The Communist project is at least superficially quite different from both its predecessors. This difference is rooted in aspects of both the definition and the goal. The definition in this case is undertaken against the background of China’s existence as a modern state with fixed borders and an enumerable citizenry; in this context the peripheral peoples become “minorities,” since the Han are over 91 percent of the population. And in this definitional process, the criteria for group differentiation are clearly separated from those for scaling. Definition of a minzu depends on Stalin’s four characteristics of a nationality (common territory, language, economy, and psychological nature), while scaling depends on the particular stage in the universal progression of history (the primitive, slave, feudal, capitalist, and socialist modes of production) that people have reached at the time of classification. Thus there is no a priori assumption that any one group—such as the Han in the Confucian project or the European Christians in the Christian project—is innately superior. In fact, there is no a priori assumption that the center consists of a particular group; Han have an overwhelming majority of positions in the Chinese state, but they do not have a monopoly, in the way that civilized Chinese constituted the center for Confucians, or Europeans for the Christian project. From this stems the further difference that the Communist project, unlike the other two, immediately grants full legal equality to the peripheral peoples.

The goal of the Communist project, on the surface, also differs from the goals of the other two. In the Communist project, the goal is not ostensibly to make the peripheral peoples more like those of the center, but rather to bring them to a universal standard of progress or modernity that exists independent of where the center might be on the historical scale at any given moment. The achievement of historical progress is thus fully independent of any approach to Chinese norms; the Russians in the pre-1991 Soviet Union, for example, were just as far along the road to socialism as the Han (maybe, depending on the stage of the current propaganda war, even farther along).

To accomplish this project, then, the Chinese Communist center implemented the most thoroughgoing definition program in China’s history: the ethnic identification (minzu shibie) project of the 1950s (Fei 1981a; Lin 1987; Jiang 1985). This project, which occupied its participants for several years and still is not complete, involved sending teams of researchers to all areas of the country where local people had claimed status as a separate minzu, and evaluating their claims ostensibly according to Stalin’s criteria, but in many cases also considering traditional Han folk categories, and sometimes giving weight to the people’s own ethnic consciousness. This resulted initially in recognition of fifty-four minzu, including the Han; two have been added since to bring the total to fifty-six.

In addition, an important part of the identification process was determining where each minzu fit on the scale of history; this was important in order to plan the political struggles and developmental campaigns that would raise the civilizational levels of the various minzu (Chen Yongling n.d.). For example, people judged to be at the late-feudal stage of the landlord economy (which is where most of the Han peasantry was judged to be also) were to undergo the violent class struggles of the Land Reform program, while those who were still at the slave stage, or even showed vestiges of the primitive commune, were subjected to a much milder process, involving cooptation of leaders to the state project, and known as Democratic Reform.

Once this definitional stage was completed, it fell to the center to do the actual civilizing—the minzu gongzuo (work) of creating autonomous regions, implementing educational and developmental plans, bringing leaders of the peripheral peoples into the Party-state apparatus that carries out the center’s project—in general, fulfilling the promise that all minzu, equal legally and morally, would march together on the road to historical progress, that is, to socialism. If some had farther to march than others, this was because of unequal historical progression up to the time of Communist takeover. But from here on out, China was to be a “unified, multinational state” (tongyi duominzu guojia) with all minzu working together toward common goals.

Contradictions between Theory and Practice

Despite these rather clear theoretical differences among the three projects, however, the actual situations of their implementation have been more complicated, due chiefly to the fact that only the Confucian project has ever been implemented by itself. Both the Christian and the Communist projects have faced competition from the Confucian project, and this has affected the outcome of the projects in various ways.

Competition between the Confucian and Christian Projects. Since the Confucian project was there first, when the Christians arrived among China’s peripheral peoples, they were always in competition with the Confucians. There were two aspects to this competition. First, the Christian project, as mentioned above, was directed not only at transforming the peripheral peoples, but also at transforming the Han; it thus not only created competing centers but defined the Chinese center as being inferior to its own, and thus in need of civilization. In many cases, as mentioned above, the peripheral peoples came out ahead of the Han on the Christian scale of civilization (at least the moral part if not the technical); this often was a result of the greater susceptibility of the peripheral peoples to conversion (see below), and it often resulted in the missionaries’ taking the side of peripheral peoples in disputes with Chinese officials, as is related in Swain’s and Cheung’s contributions to this volume.

More importantly, competition between the Confucian and Christian civilizing projects often gave the peripheral peoples an opportunity to choose. And since the definitional aspect of the Confucian project assumed the moral rightness of certain exploitative economic arrangements (prominently working for Han landlords or Han-appointed native leaders—tusi and tumu), while the Christian economic approach was more benign or sometimes even helpful, peripheral peoples were prone to choose the missionaries as protectors against their Han oppressors or exploiters. This, of course, meant ready converts, as well as the missionaries’ more positive evaluation of peripheral peoples.

Confucian Co-optation of the Communist Project. As was mentioned above, in the Communist project, everything was supposed to be different: the center was progressive but not explicitly Han, and all minzu were equal now. But in fact the Communist project has run into two kinds of obstacles, both of which render it in practice less like its own theory and more like the Confucian project, with culture as the measure of centrality and Han as the actual center.

The first obstacle is simply ingrained prejudice and local negative evaluation of minorities. This manifests itself at practically every level of Chinese society today. I have spoken to Han scholars who are experts on the Yi but speak nothing of the Yi language, and who can tell one in great detail the particulars of the dirtiness, backwardness, and stupidity of the Yi and other minorities. The first time I visited a Sani village in Yunnan, I was told by one of my Han companions that “what these people need is culture,” and he didn’t mean traditional folktales or minority dances. He meant culture in the classical sense of wenhua, the literary transformation that brings forth civilization. One Han official who had worked on a government forestry project in the middle of a Yi area had lived there twenty years and never tried Yi food; he was sure it would be dirty and make him sick.14

Such attitudes are extremely common at the local level, but they manifest themselves among the highly educated as well. A minority graduate student of my acquaintance, for example, used to dread revealing her identity in a crowd of students; as soon as they found out she was a minority, she said, they would begin simplifying their vocabulary. A schoolmaster in a successful minority education program in the Southwest complained about how difficult it was to educate these people, not only in conventional academic senses but in the social sense of persuading them to give up such primitive practices as dating in high school.

As long as such an innate, almost visceral Han sense of superiority remains, the actual program of the Communist project will be based on the unconscious assumption that Han ways are better, more modern ways. Peripheral peoples who act like Han—who are educated, Hanophone, cultured—will be treated equally with their Han compatriots. But it is Han culture that sets the standard.

This lingering social prejudice is reinforced by a second obstacle, which stems from the heart of the Communist project itself: the theory of the five stages of history. With this theory, which Chinese schoolchildren learn as objective fact on the level of the periodic table of the elements or the order of planets around the sun, the scaling of minzu can claim a scientific validity, one that is objective in the sense that the standpoint of the viewer does not change the picture. But it just happens that the Han (along with the Manchus and perhaps the Koreans) are higher on this objective scale than any of the other groups. This fits in handily with the aforementioned continuing Han prejudice against peripheral peoples. If the Dai actually are feudal, then of course they need to be brought up to the socialist stage, and the example for doing that are the Han, who moved from the semifeudal, semicolonial to the socialist level in the 1950s. The end result is that there is in fact very little challenge to the assumption of the Confucian project—the assumption that Han ways represent true culture and are therefore a model for other minzu to follow.

Some authorities have seen this Communist project as one that will ultimately lead to assimilation (Dreyer 1976:261–62; Heberer 1989:130), and in a sense it may amount to that in the long run. But we must remember two things. First, the long run is very long—it is the run all the way to communism, which is inconceivably far in the future (unless it was in the summer of 1958). Until then, according to Leninist theory, minzu will remain (Connor 1984:28–30; Dreyer 1976:262). And because minzu are destined to remain for a very long time, it is important that their differences are preserved. But, according to the theory of the Communist project, some minzu differences get in the way of progress along the stages of history, so these must be eliminated. The things that remain are those that foster ethnic pride, but do not impede progress. This is why the Communist state has placed so much emphasis on festivals, costumes, and the inevitable dancing in a circle, which is close to universal among China’s minority minzu.

PERIPHERAL PEOPLES’ REACTIONS TO CIVILIZING PROJECTS

The Development of Ethnicity

If the civilizing center initiates and organizes a project by developing an ideology of definition and scaling, the peripheral peoples, those worked on as objects of the civilizing project, respond at least partially by developing an ideology of ethnicity or ethnic consciousness. (I say “developing” because that word has a shaded scale of meanings: something can be developed de novo where it has not existed previously, or something that already exists can experience development in the sense of growth or change.) And so it is with the ethnic consciousness of peripheral peoples as the projects work on them. Such consciousness may already exist, but it will be sharpened, focused, perhaps intensified by the interaction with the center. Or in some cases, a peripheral people that has no ethnic consciousness may develop one in response to the pressures of the civilizing project.

Exactly what constitutes ethnicity or ethnic consciousness is a subject of much debate in anthropological circles (see Keyes 1981, Bentley 1987, and Williams 1989 for useful summaries at various stages in the evolution of the controversy), but it is probably inoffensive, at least, to define ethnic consciousness as the awareness of belonging to an ethnic group, and to define an ethnic group as a group that has two characteristics to its consciousness. First, it sees itself as solidary, by virtue of sharing at least common descent and some kind of common custom or habit that can serve as an ethnic marker (Nagata 1981). Second, an ethnic group sees itself in opposition to other such groups, groups whose ancestors were different and whose customs and habits are foreign, strange, sometimes even noxious to the members of the subject group.

There is further controversy as to when—under what circumstances or in what sorts of societies—ethnic groups and ethnic consciousness arise. For Abner Cohen (1981), ethnicity arises out of new kinds of interaction between peoples, where they have to confront each other in novel situations. For Soviet and Chinese Marxist scholars, ethnic groups arise only in situations in which there are social classes, so that different groups of people, taking different parts in the social division of labor, form perceptions of group interest and of opposition to other groups, leading to the commonalities of territory, language, economy, and culture that are the defining characteristics of a “nationality” (Li Shaoming 1986, Gladney 1987, Shanin 1989). In a recent article, Brackette Williams sees ethnic consciousness as arising out of the confrontation between a modern nation-state (or a governing group that is attempting to constitute itself as such a state) and minority peoples living within that state’s territory (1989). Despite superficial differences (and a sometimes regrettable accusatory tone), it seems to me these authors are all pointing toward the same thing: the development (invention or change) of ethnic consciousness in situations where a group is confronted in some way by an outside power with whom it is in competition for resources of some kind, whether they be material (as in the Marxist formulation of class struggle and the division of labor) or symbolic (as in the conferral of not-quite-us status to minority groups even in states that attempt to insure the legal equality of majority and minority).

The situation of the civilizing project clearly fits right into this paradigm. When peripheral peoples are confronted with a center that not only attempts to rule them and the territory they inhabit, but also to define and educate them, they are forced to come to terms with who they are and with how they are different from those who are attempting to civilize them. So quite naturally they rethink their own position and their own nature, and in most cases, they seem to come up with a self-definition that is ethnic in the terms outlined above.

If developing an ethnic consciousness is an almost inevitable result of becoming the object of a civilizing project, then this development has two aspects: the development of consciousness of belonging to a group, and the development of consciousness of being different from other groups. The form that these developments take can vary greatly according to the pre-existing nature of the peripheral group and its preproject consciousness (if any), the definition imposed by the project, the perceived harm or benefit the project promises to confer, and the relative power of the center and the periphery in the individual situation. Some examples, drawn mainly from the case studies in this volume, may help to clarify the range of possibilities.

Miao as a designation for certain upland peoples of the Southwest is at least as old as the pre-Imperial Shujing (Classic of history), in which the San Miao are referred to as the aboriginal inhabitants of the Yangtze River region. But the modern consciousness of a Miao ethnic group is still tenuous, and may never completely gel. We see in two different articles in this volume, however, ways in which first the Christian, and then the Communist civilizing projects have contributed to the development of this consciousness. Siu-woo Cheung’s treatment of the role of Christian missionaries in the Miao social movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries shows how the image of Jesus as savior was fused with an earlier messianic idea of the Miao King to form a focus of identity for Miao groups all over northeastern Yunnan. And Diamond shows how the imposition by the Communists of the category Miaozu for a wide range of peoples in several provinces has prompted at least some of those people to think of themselves in some contexts as part of this larger group—an ethnic consciousness probably helped along today by frequent visits of Hmong (one group included in the category Miao) from Southeast Asia and North America. Here is a case of a category of linguistically related peoples, which did not previously constitute in any sense a group, developing the idea that they are members of a kind of collectivity that transcends local differences and includes them all. These people have always had the second component of ethnic consciousness—the realization that they are different from the Han. What they lacked previously, but have gained partially as a result of these projects, is the idea that they are related to each other, that they are all members of a community.

The Sani, described here by Swain in their interactions with Catholic missionaries, present a rather different picture. In certain ways, the Sani before Fr. Vial’s mission were something like one of the local Miao groups before the early-modern ethnic movements. The Sani were one of those local groups classified by the Han as Luoluo (usually spelled Lolo in European sources), a congeries of peoples, speaking related languages, stretching from northern Vietnam to western Sichuan. They had no name in their own language for the Lolo as a whole (this was a Han category), but they did refer to themselves as Ni or Sani. Vial took a liking to them, seeing them as his children, his charges, as morally superior to the cunning and wily Han, even if they were technically more primitive and politically much less powerful. But he engaged in no action that fostered any kind of union of different “Lolo” groups, as Pollard and his colleagues had brought together different subgroups of the Hmong. The reaction to Vial’s project seems to have been a heightening of the Sani consciousness (they still are loath to recognize their official status as Yi, the polite successor term for the category formerly called Luoluo) without creating a new consciousness of a wider identity.

In a slightly larger arena, the Yi in general (described by Harrell here, though this chapter deals only peripherally with ethnic consciousness; see Harrell 1990 for a fuller treatment) have experienced a process quite similar to that undergone by the Miao since 1949. A conglomeration of linguistically related groups has been incorporated as a minzu, and educated elite members of this category, at least, have at various times seen their Yi identity as being equal to or greater in importance than their local identity as Nuosu, Lipuo, Axi, Luoloupo, Nasu, and so forth. But the process here, as with the Miao, is far from complete.

The Manchus present a still different case. As outlined in this volume by Shelley Rigger (see also Crossley 1990a), Manchu identity went through a series of stages as the position of Manchus in the Chinese state went from challengers to conquerors to overlords to defeated remnants. Manchu was originally a political category, consisting of followers of Nurgaci and his descendants; it was not ethnic in the sense of including notions of descent or of common ethnic markers. As the military banner organization changed with the stabilizing of Manchu rule in the mid-Qing dynasty, however, the Qianlong emperor, worried that the basis for Manchu consciousness was eroding, consciously attempted to “ethnicize” their identity, drawing especially on notions of equestrian martial traditions and shamanistic rituals. In a sense, he was reacting to his own civilizing project, in which his people had become successful and stable rulers of China, and thus inevitably had begun to identify with China, to speak and write the Chinese language, to participate in many aspects of Chinese life. When the Manchu rulers were overthrown, there was no longer a context for ethnic consciousness, and in most Chinese cities Manchuness quickly dissolved except as a tale of ancestry. It was to be revived, however, by the Communist project, which for unclear and perhaps purely scientific reasons reconstituted the Manchus into a minzu, which they remain today. Some of them are taking language lessons.

Qianlong’s attempt to revive Manchu identity accomplished the opposite of what happened to the Miao in the nineteenth century. The Manchus already had a sense of themselves as a solidary group; they were the conquerors and rulers. What they did not have was a clear sense of their ethnic markers, of how they were different from the Han. This the Manchu cultural revival of the mid-eighteenth century attempted to give to them. The second (or Communist) revival, which continues as I write, is more ambitious, for after the fall of the Qing most people with Manchu ancestry had neither a clear group consciousness nor a sense of how they were different from the Han; in fact, most of them were not different in any linguistic, territorial, or cultural sense, and retained only a vague sense of identity without clear markers or borders.15

A somewhat similar process has occurred among the Bai of Yunnan, as described by David Y. H. Wu (1989, 1990). These people, known formerly as Minjia (civilian households) live around Er Lake in western Yunnan; their ancestors may have been the rulers of the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms of the ninth through thirteenth centuries. Though they have their own language, which has so far eluded the classificatory efforts of linguists because of its extensive borrowings, they were well on their way, in the decades before 1949, to complete assimilation as Han Chinese. Francis Hsü’s famous monograph, Under the Ancestors’ Shadow (1948), for example, makes little mention of the Bai origin of its subjects, whom Hsü takes as an example of Chinese peasant culture and personality. But in the process of ethnic identification, the Bai idea was revived, and since then minzu policy has encouraged the development of ethnic markers, such as costume, music, and festivals, and the Bai have been given a minzu identity on the same level as other peripheral peoples. Here is a case like the second Manchu revival, where there was little consciousness of group solidarity or opposition to others, but these were revived and in some cases re-created by the Communist project.

The Yao, treated here by Ralph Litzinger, underwent a process formally similar to that experienced by the Manchus, but in a fundamentally different context, since they have always been the ruled rather than the rulers. Yao appears originally to have been a political category of upland peoples who could range across the South China mountains without paying taxes or corvée. Even in the Da Yao Shan (Great Yao Mountains) area, they speak three unrelated or distantly related languages, and their other customs and beliefs are quite different; one group, the Tai-speaking Lakkia or Tea Mountain Yao, were lords of the other groups before the Communist takeover. But with the Communist project, which includes the idea that minzu share cultural markers (see below), they have been led to develop a consciousness not only of being a we-group, opposed to the Han, but of having a large number of cultural continuities, including origin myths and the practice of ritual Daoism. The Yao have developed this consciousness in response to pressure of a civilizing project imposed from outside, unlike the eighteenth-century Manchus’ response to their own voluntary but disturbing co-optation by the culture of which they themselves were the overlords.

The Dai of Sipsong Panna, described in this volume by Shihchung Hsieh, present a still different case, one of a people originally independent on the farthest periphery of the Sinocentric world, who were forced to move from a consciousness of themselves as a nation, a people who ran their own state, to an idea of themselves as an ethnic group within a larger political system. Previous to their partial incorporation into the Nationalist state, and their fuller absorption under the Communists, they certainly had a fully formed ethnic identity; they were a solidary group organized around their lords (chao) and they were distinct from the subordinate upland peoples of their own kingdom (they knew little about the Han except as a political power to be reckoned with). When they were included within the borders of China, the most important other to which their ethnic identity was contrasted shifted from their upland vassals to their Han overlords. But the boundaries of the group and its internal markers have remained basically the same.

Then we have the Mongols, treated here by Almaz Khan and Wurlig Borchigud. There have always been political confederations on the northern marches of China; several of them ruled China at various times. But it seems that, prior to the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the important identifying marks for people in this area were their allegiance to particular lords or confederations, and their membership in descent groups that held claims to certain political titles. As Pamela Kyle Crossley has recently demonstrated (1990b), there was in the late Ming dynasty no classification by language or culture in the modern sense, but rather a classification by ecological adaptation, into herders, agriculturalists, and people who did a bit of both. It is with the decline of such obvious distinguishing characteristics that the ethnic markers and the notion of common descent have become important definers of the category Mongol. Almaz demonstrates this process with regard to descent from Chinggis Khan, which has changed from a political privilege to an ethnic marker; Borchigud shows how, with the further erosion among urban Mongols of cultural markers such as language (both Borchigud and Almaz speak Chinese as their native language), common descent and endogamy have come to be the markers that separate Mongols from Han. The Mongols, in a sense, did not think much about group identity until recently; their difference from the Han was obvious and ecological until the late nineteenth century, and since then has become an aspect of group identity.

As a final example, we ought to examine the Hui, the strangest ethnic category recognized by the Communist project. There is no real definition of Hui in terms of Stalin’s four criteria: they have no common territory, being scattered throughout China; no common language, since they almost all speak Chinese; and no common economy or culture either (Gladney 1987, 1991). There are about eight million Hui scattered around most of China; concentrations lie in the Gansu-Ningxia-Qinghai border region, in cities of North China, and along the southeast coast. The only thing they may have in common is a tradition of descent from Muslims, although not all of them practiced Islam, even before the ascension of godless Communism. In the areas of the country where there are great concentrations of Hui Muslims, such as the Gansu-Ningxia-Qinghai area, Hui have long had an ethnic consciousness that has opposed them to the Han, Tibetans, Turkic Muslims, and Mongolians who also inhabit that area (Lipman 1990; Gladney 1988). But in the Southeast, no such consciousness existed until certain groups remembered their Islamic ancestors and applied for Hui minority status on that basis. When the status was conferred, they had to become Muslims, so they began giving up pork, Chinese temple worship, and other non-Islamic customs (Gladney 1991). Here is a case where a local ethnic consciousness was created virtually ex nihilo by the Communist project; an ethnic consciousness for the whole minzu, like that for the Yi and Miao, probably now includes only members of the elite, but will certainly spread, perhaps faster among the Hui, since the peasants of the Northwest, as well as most city dwellers (Gladney 1991) already have a local ethnic consciousness, and those in the Southeast have gone through the conscious process of acquiring one.

Meshing Project and Reaction: The Provisional Granting of Voice

The reactions of peripheral peoples to civilizing projects are not, however, limited to the development of ethnic identity. Insofar as civilizing projects are wholly or partly successful, they include the participation of the peripheral peoples. And in fact, as long as peripheral peoples agree, at least on the surface, to the terms of definition and scaling imposed by the civilizers, the civilizees will be granted a voice to speak to themselves and the world about the success of the project. In this sense, the answer to whether the subaltern can speak is that the subaltern can speak on the sufferance of the civilizer. Voice is granted on the provision that it will speak in favor of the project, or at least in the project’s terms.

From the standpoint of the civilizers, the ideal form of the taking up of voices by the subaltern is the creation of “compradore elites.” The term compradore (Portuguese: “buyer”) originally referred to a Chinese who was an agent for a foreign company operating in China. But in the broader sense, it refers to members of peripheral or colonized peoples who participate in a colonizing or civilizing project. We can see examples in this volume in Litzinger’s discussion of Yao cadres, who rule not only on behalf of the state, but on behalf of the state’s “minority regional autonomy” policy. These people are often among the real leaders of the Yao communities, and it is they more than any Han bosses who determine the success or failure of the developmental aspects of the civilizing project. At the same time, the definitional aspects of the project, the classification and standardization of language and other cultural traits, depend heavily on the participation of Yao scholars.

We find another example of peripheral elites taking up a permitted voice in the Christian church leaders who emerged among the Miao (Cheung, this volume) and Sani (Swain, this volume) in quite divergent circumstances early in the twentieth century. In the Miao case, Christianity was taken up by leaders and participants in ethnic social movements, but it remained, in some places, as an outright ethnic marker of the Miao long after the movements had been suppressed or run out of steam. In the Sani case, there was no massive movement, but Fr. Vial, for all his Orientalist assumptions and writings about his childlike flock, did provide the Sani a counterweight to Chinese officialdom. Similar experiences are reported by Shepherd (1988) and Hsieh Shih-chung (1987) for missionized aboriginal peoples in Taiwan.

More than this, the simple adoption of state-imposed minzu identities is a weak form of peripheral peoples’ speaking in the idiom of the civilizing project. This, however, is not as satisfactory a result from the viewpoint of the civilizers. The ethnic identity, originally weak, unformed, or nonexistent, once imposed can serve to unify resistance or even rebellion against the center that created the category that unifies. Thus the Pan-Mongol sentiment that became so much stronger and so much more overtly anti-Han during the Cultural Revolution of 1966–76 (Borchigud this volume; see also Jankowiak 1988). And in a sense, even the successful anticolonial rebellions that ended up dismembering the European empires in the mid-twentieth century were perpetrated in the name of nations that were originally the creations of the colonizers.

The paradox of civilizing projects is that they can, in some circumstances, turn back on themselves. With their avowed (and often sincere) intention to raise the cultural or civilizational level of the peripheral peoples, civilizers also make an implicit promise to grant equality, to share power, to give up ultimate control over how and when the subalterns speak. When the first happens without the second, when the peoples of the periphery gain advancement without equal empowerment, revolts can be the result. This has clearly been the case in almost every overtly colonial situation in this century; it may turn out to happen in Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and parts of Xinjiang as well. On the other hand, in some cases, as demonstrated above, the process has not gone that far yet, and the definition of peripheral peoples as less civilized, and thus legitimately subordinate in the political and economic order, still holds.

A civilizing project is thus not a unified thing, either in its purposes and methods or in the reaction of the people civilized. Only one thing remains constant: the assumption of cultural superiority by the politically and economically powerful center and the use of that superiority, and the supposed benefits it can confer on the peripheral peoples, as an aspect of hegemonic rule.

As indicated in the beginning of this introduction, civilizing projects have not been peculiar to China. In fact, much recent scholarly attention has been devoted to colonial discourse, almost always analyzing the ideological side of European colonial domination of Asian and African peoples in the eighteenth through twentieth centuries, as well as its neocolonial descendants in the postwar policies of the United States in particular. Much of this work is insightful and useful; it gives us some insight into the nature of the colonial enterprise. In addition, recent work, such as the articles collected in the November 1989 issue of American Ethnologist, is beginning to look beyond the simple dichotomy of colonizer and colonized to try to define varieties of colonial discourse as they changed over time and as they were different from one colonizer to another—bureaucrat and missionary, aristocratic administrator and peasant soldier, Frenchman and Englishman, man and woman. But this introduction, despite its admirable objective of putting the European empires of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into perspective, does not even mention the Japanese colonial empire, which was contemporaneous with those European empires, let alone the Confucian project, which was going on even as China itself was the object of Western imperialism (Cooper and Stoler 1989).

This is not to maintain, of course, that every book has to be about everything; this one is only about China and its periphery, for example. But it is still necessary to point out that those of us who study the civilizing centers of the East have it incumbent upon ourselves to begin making our voices heard in the growing scholarly community discussing civilizing projects generally; it would be ironic if a community dedicated to deconstructing the ethnocentric formulations behind its own colonialism ended up excluding colonialisms of other centers. It is in this spirit that we offer Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers to the wider community.

1. In writing and revising this introduction, I have benefitted greatly from written comments, discussions, and suggestions about sources provided by Ann Anagnost, Peggy Swain, Simon Cheung, Norma Diamond, Ralph Litzinger, Hehrahn Park, Tsianina Lomawaima, Nancy Pollock, Jack Dull, and Kent Guy. The odd turns of phrase, both intentional and unintentional, are entirely my own.