7 / Baiwu: Nuosu in an Ethnic Mix

If Hxiemga are a haunting presence for the people of Mishi, they are neighbors, rivals, and sometimes friends for many Nuosu people in Baiwu, a township in Yanyuan, far on the other side of the Anning and Yalong Rivers. There Nuosu, though now numerically dominant, were the last ethnic group to arrive and have always lived with the everyday presence not only of Han, but of Prmi, Naze, and sometimes other ethnic groups. In Baiwu, as contrasted to Mishi, we come face-to-face with the operation of ethnicity and ethnic identity, where common history, descent, and culture all serve both to tie ethnic groups together as collectivities and to mark the boundaries between them.

Baiwu Township is located thirty-five kilometers due north of the county seat of Yanyuan, reached in less than an hour on a well-graded dirt road (maps 4 and 5). The little township headquarters seems much more like an actual town than does the corresponding settlement at Mishi; in addition to the usual one-and two-story courtyard buildings housing the township Party and government, the forestry bureau, the credit cooperative, the local hospital, and the radio- and post administration, there are also a number of small shop-houses that harbored, in 1993, three small restaurants, two video parlors, six lightly stocked state stores (there were noticeably more a year and a half later), nine privately owned stores, five one- or two-table pool halls, and two little hotels. The smaller stores sell more or less the same things—liquor, beer, soft drinks (which are too expensive for most people), cigarettes, matches, candles, toilet paper, batteries. The larger ones offer clothing, and in the middle of the day when the farmers come in to market, shopkeepers set out tables on the edge of the single, paved street, offering clothing, cloth, and yarn, which Nuosu and Prmi girls use to do their hair in fancy styles.

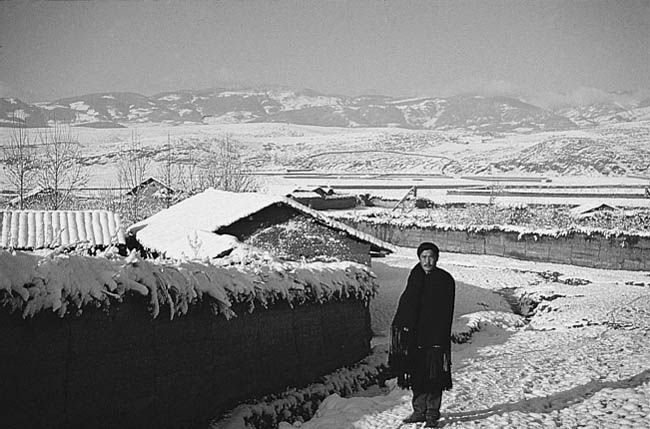

There is market activity in the middle of the day every day, and the street in the winter sunshine is a riot of color, dominated by the bright skirts, blouses, and embroidered headpieces of the Nuosu women and girls, along with the more sedate, single-colored pleated skirts and embroidered aprons of the Prmi women; bright blouses and blazers, in the city style, worn by young Han women; and the swaying fringes of the black, decoratively stitched vala of Nuosu men and women (figs. 8, 9). When farmers come in by horse or cart, one may glimpse a saddle painted in the same three-colored patterns found on the dishes from Mishi, and a few horses are often tied up near the unfinished fountain at the lower end of town. All of the stores are open at this time, and sheep or chickens may be for sale by people who have come in from the country; when someone comes with meat from a freshly killed yak, buyers cluster around arguing prices in several languages.

FIG. 8. Vala as winter coat: Ma Erzi on a chilly morning

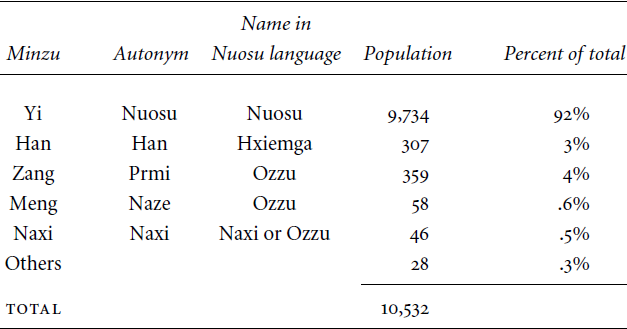

Contiguous with the town are two villages. Above the town is Hongxing (Red Star), whose population is entirely Nuosu, mostly quho, from the clans of Synzy, Lama, Ashy, Molie, and Jjike. Below the town is Lianhe (United) Village, which consists of Han, Prmi, Naze, and Naxi, with no Nuosu. Outside the immediate vicinity of the town, the population is almost entirely Nuosu; the only exceptions are a couple of villages that are part Nuosu and part Prmi. In sheer numerical terms, Baiwu Township is thus overwhelmingly Nuosu; the minzu distribution of the population in 1993 is shown in table 7.1. In Baiwu Administrative Village, however, the population is only 81 percent Nuosu, and this includes two more distant natural villages, Yangjuan and Pianshui, that are entirely Nuosu. In the villages attached to the town, then, the population is slightly over half Nuosu and slightly less than half everything else, with 160 Han, 57 Prmi, and 60 Naxi. Nuosu who either live in Hongxing or come to town thus have to deal with members of other ethnic groups on a regular basis.

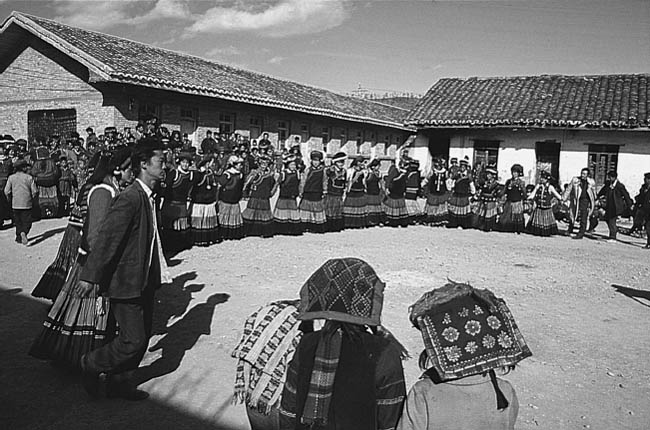

FIG. 9. Vala as ceremonial dress: a member of the groom’s family at a wedding, dancing to bring gifts to the bride’s family

Baiwu, like Mishi, was once the headquarters of a qu, a unit comprising four townships, which was abolished in most of Liangshan in 1992. But Baiwu still retains the government offices of the forestry bureau, grain administration, postal administration, and hospital, and most important, it contains, like Mishi, both a six-grade elementary school and a three-grade junior middle school. Both schools are located on the upper side of town, contiguous to the Nuosu village at Hongxing.

Despite its relatively good transport network and its proximity to town, because Baiwu lies in Yanyuan, one of the poorer counties in Liangshan, economic development has proceeded slowly here, as in Mishi. Electricity was connected to the town only in January 1993 (I was there for the grand celebration), and although it had reached most of the village homes in Hongxing and Lianhe by late 1994, at that time it was still to be connected even to the nearby villages of Pianshui and Yangjuan, and to the plateau area of scattered housing called Lamata, let alone to any of the more remote villages around the edges of the Baiwu basin or in the foothills. There is no industrial or craft production whatsoever, and even agriculture on the broad Baiwu plain is restricted by the cold climate at this altitude, as well as the lack of rainfall outside the summer season. The township head told me that he thought the per capita income for 1992 had been about ¥340, but he managed to figure it in a manner that would reduce it to ¥240, which brought Baiwu in below the poverty line and thus retained eligibility for certain kinds of economic assistance. In fact, one of the cadres in the local finance office told me that the total tax and other monetary revenue for the local government was only about ¥80,000 per year (about ¥7 per person), compared to the state investment in development (mostly infrastructure) of around ¥300,000.

TABLE 7.1

Population of Baiwu Township by Ethnic Group, 1993

According to most local cadres and many other people, however, this “backwardness” was about to change; in 1993 and 1994 they saw Baiwu as on the road to development and prosperity, all because of apples. A wealthy entrepreneur who hails from Lamata in Baiwu Village explained it to me: Yanyuan apples are of the highest grade, along with those grown in only a few other places in China, some of them in Xinjiang. The market right now is unlimited, as urbanites strive to include more fruit in their diet, and even rural areas in the populous parts of Sichuan, not to speak of the expanding populations of Panzhihua and Xichang, will always buy more apples. All that is needed for the crop to really take off, he said, is to build a decent highway between Yanyuan and Xichang. This, he also said, would make up for the exploitative way that the Han-dominated government has treated the Nuosu homeland of Liangshan.

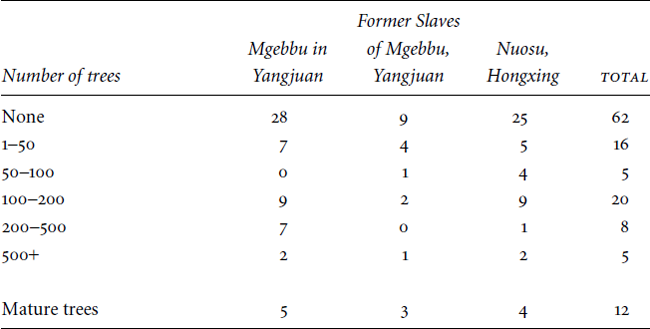

TABLE 7.2

Apple Orchard Ownership among Yangjuan and Hongxing Households

In fact, a large number of people all over central Yanyuan are planting apples, getting long-term leases (chengbao) on the land, and borrowing money from friends, relatives, and the agricultural bank to buy the seedlings. An incomplete but not systematically biased survey of 119 households in Hongxing and Yangjuan yielded the numbers in table 7.2. We can see from this table that nearly half of the Nuosu households surveyed (57 of 119) had planted apple orchards. In the mid-1990s, Han and other ethnic groups were also joining the rush. Many other families who had not yet planted in 1993 were preparing to plant. Everywhere on the Baiwu plain, one sees neat grids of trees, trunks whitened with a protective substance, all enclosed by mud walls that keep out marauding livestock.

Some of the orchards, as table 7.2 indicates, are quite large. Only a few of the orchards are mature, that is, planted six or more years ago and beginning to yield significant quantities of apples. The largest mature orchards in 1993 had 150 to 160 trees, which at a yield of 100 jin (one jin equals .5 kg) of apples per tree (some large trees yield several hundred), at a price of ¥.8 per jin, would bring in income of about ¥12,000, minus expenses. When the really big orchards, ranging up to 1,000 trees, come on line, if the price holds there will be a big infusion of income into this area, and many people are hoping that this will be the beginning of sustainable economic development. As of 1993, however, this was mostly a fond hope; the township head told me there were no more than four true ¥10,000 families in the township.

HISTORY

There is little doubt that the Prmi, Naze, and Naxi came to Baiwu before the Han or Nuosu. The area that is now Yanyuan and Muli was incorporated into the Chinese empire during the Han dynasty, lost again during the period of disunity, recovered again in the early Tang, but then lost to Nanzhao and Dali from the late eighth century until the Yuan reconquest in the 1250s (Fu 1983: 130–38); during the Ming period it was transferred from the jurisdiction of Yunnan to that of Sichuan. Around the old garrison town of Yanjing (Salt Well), imperial administration prevailed from the Ming on, but the specific political authorities that ruled the outlying regions date their imperial mandates as tusi back to only the early eighteenth century. The plains and valleys around Baiwu sat at the conjunction of the domains of three different tusi. The territory around the current site of Baiwu Town belonged to the Great Lama, or king of Muli (see Rock 1930), who was established officially as a tusi in 1710. He was ethnically Prmi but was also a monk-official of the Gelug-pa sect, which ruled Tibet, and was supported religiously by an incarnate lama whose seats were the same three monasteries, all within the boundaries of today’s Muli County, from whence the Great Lama ruled.

In addition to the three great monasteries of the Great Lama’s regime, there were also the “twenty-four little temples,” one of which was only about a fifteen-minute walk from today’s Baiwu Town. This temple, according to a descendant of the local official family, had from two to five monks in the early twentieth century. The civil administration was handled by an official of the Shu family (now classified as Naxi) called the bazong; other members of what are now the Naxi, Zang (Prmi), and Meng (Naze) minzu owed labor services to the bazong, and through him to the Muli administration, in return for farming the land. Some of the families also owned land privately in this area, and Han farmers came into the region at various times. They paid rent but did not owe labor services.

Toward the east of Baiwu Town, there were similar arrangements, but there the land belonged to the Guabie tusi, who was ethnically Naze, and also enfeoffed in the early eighteenth century. Finally, some of the land to the west of Baiwu Town was controlled by the Guboshu tusi, another Naze ruler enfeoffed at about the same time. Both of these tusi families professed Buddhism and supported small monastic establishments; unlike the Muli ruler, neither was a monk nor could boast an incarnate lama in his little monastery.

It seems probable that the population under the rule of these various tusi up until about 1800 was quite sparse; people report that even up to the 1950s, there were a lot more trees on the foothills and even on the plains than there are now. The small population consisted mostly of speakers of Prmi and Naze (and perhaps Naxi), who were nominally Buddhists but also practiced many rites of native priestly traditions called hangue (Prmi) and ndaba (Naze).1 There may also have been Han tenants from time to time; although no Han families in the immediate Baiwu area now trace their ancestry back that far, there was a place called Yunnan Village, near the current settlement of Shanmen on the road from Baiwu to Yanyuan City, whose population was mostly Han at least six generations ago. There are still some Han living in Shanmen, according to township population statistics; I have not been there.

The ethnic composition of this area, however, was dramatically altered beginning with the migration of Nuosu clans out of Zhaojue and Puxiong eight or nine generations before the present (see chap. 5). Probably sometime in the late Qianlong period, in the late eighteenth century,2 two branches of the nuoho Loho clan left Zhaojue, and eight generations before the present middle-aged men, they settled in various parts of Yanyuan and the remote northern regions of Yanbian. One of the regions where they settled was Baiwu, where most of them lived to the north and northeast of the town around the present site of Yangjuan.

Among the retainers who migrated with the Lohos or came a few decades afterward and became their retainers were the Mgebbu, Ali, Ddi, and Jjizi quho clans. These Nuosu clans, through both land purchase and warfare, gradually expanded at the expense of the representatives of the king of Muli, the bazong and his retainers. By the early twentieth century, about one thousand mu of land, mostly on the side of the river toward Baiwu Town, still belonged to the Ozzu (Prmi and Naxi); the rest was considered territory of the various Nuosu clans (both nuoho and quho), while individual plots were privately owned and patrilineally inheritable. In general, relations were peaceful most of the time, and there was considerable co-godparenthood between Nuosu and Prmi (and sometimes Han), to the point that my collaborator Ma Erzi calls a lot of people shushu (father’s younger brother) who are Prmi or Han. But there were fights also, including a skirmish that reduced the territory of the bazong considerably in the 1940s, and other smaller feuds over real or imagined slights. For example, when one of the powerful Mgebbu elders was drinking with a local Ozzu shortly after one of the Nuosu elder’s cattle got into the Ozzu’s field and ate some of his grain, the Ozzu leader, a man with a very fierce reputation, became drunk and struck the Nuosu elder, at which point the Mgebbu went to an area called Gangou and rounded up about twenty clan relatives, who trashed the Ozzu’s house and stole, slaughtered, and ate his best plow ox. According to the man who told me the story (the grandson of the Nuosu leader), the Ozzu realized he was wrong, and thus accepted compensation from the Nuosu rather than prolong the dispute.

It may be that such fights between Prmi and Nuosu were no fiercer or more common than fights among Nuosu clans themselves, such as that between the Mgebbus and Qumos in the 1940s and ’50s, which resulted in a prohibition on intermarriage that has lasted until the present. In addition, of course, there were ruler-subject relations between the Lohos and their quho retainers. According to knowledgeable men of both clans, the obligations of the retainers to the lords included gifts of liquor and a pig’s head at the New Year, weddings, and other occasions; fighting for the lord whenever he went to war against other nuoho; and three days’ labor per month on the fields of the lords. Some quho, however, ignored the latter stipulation or, if they were rich, sent their slaves to fulfill it.

In the democratic reforms of the late 1950s, people were classified according to their ownership of land and slaves, rather than their caste position, with the result that many of the Mgebbus and other wealthy retainer clans were classified as slavelords or as wealthy producers, a term equivalent to “rich peasants” in the Han areas. Others, mostly quho and mgajie, were “half slaves,” and of course slaves (gaxy) were classified as slaves. Some of the Lohos, as well as members of other nuoho clans with whom they intermarried, initially cooperated with the Communist authorities but turned rebel when the policy became harsh; certain Loho families lost large numbers of men to war and disease during this time. Other Nuosu, particularly poor peasants and slaves, joined the Communist Party, and some of them fought in the militias who put down the rebellions.

Nuosu seem to have been the only outright rebels against the reform policies of the late 1950s, but they were not alone in having their relations of production disturbed by the democratic reforms; the bazong family also lost its traditional base in land stewardship and became ordinary farmers.

Immediately after the democratic reforms came collectivization. At this time, there were large movements of population, which ended up producing the settlement pattern that persists to this day. The dispersed housing of Lohos, various quho clans, and slaves to the north of the town was disrupted when the Lohos all moved out, to areas near Yanyuan city among other places, leaving very few nuoho in the entire Baiwu area. The Mgebbus were called together by one of their leaders into the present village of Yangjuan, where they are now numerically predominant, while most of the mgajie and gaxy settled in Pianshui, a village that had a reputation during the time of collective agriculture as the poorest team in the brigade. Members of various clans who lived south of town were brought together in the new village (then a production team) of Hongxing, while members of every ethnic group other than Nuosu were clustered into the Lianhe production team, centered around the imposing old stone house of the bazong, which stands to this day. The longtime Nuosu Party secretary of Baiwu Village (then brigade) told me that the ethnic division was agreed upon by everyone. Not only would the Nuosu and other ethnic groups be able to conduct all their local affairs in their own language this way (all of the Prmi and Naxi spoke Han fluently), but also people just “felt better inside” being grouped with their own kind. North and northwest of town, however, the old pattern of dispersed housing remained and continues today, often with several hundred meters between each compound or little cluster of compounds.

From the time of the Great Leap Forward on into the Cultural Revolution, there was also an attempt to open up more land for farming, with the result that many great forests were cut down, and the plains and foothills around Baiwu have not regrown their former forest cover. Residents of the area lament this destruction almost constantly.

During the Cultural Revolution, Baiwu was not immune to the struggles and factional attacks so familiar to students of China proper. Red Guards from Yanyuan Town came as far as remote Yangjuan to attack former slavelords, and one man, who was twenty-two at the time of the democratic reforms, was strung up on the rafters of his own house for several hours while the Red Guards went to attend to other business. When they came back to administer a further beating, the former young slavelord’s wife had enough, lashed out at the Red Guards with red-hot fire tongs, and cut her husband down. After this, the radicals did not return. Factional disputes also resulted in the temporary overthrow of the local cadres, but their positions were restored within a year.

In 1982 collective agriculture was dismantled, and land divided among individual households of all ethnic groups. There was, however, not much in the way of economic development until the late 1980s, with the beginning of the commercial fruit industry.3

LANGUAGE AND SCHOOLING

In Baiwu there is no single predominant language. Nuosu and Han vie for supremacy in different contexts, with Prmi relegated to a distant third, a locally moribund tongue used only by a few older people, and by them only at home. Both Nuosu and Han, on the other hand, are languages both of everyday conversation and of official discourse.

Just about everyone under fifty, and a considerable number of the older men and women in the town of Baiwu and its attached and nearby villages, are fluent in both Nuosu and Han. Sometimes this is not entirely obvious at first glance. For example, Ma Erzi is quite friendly with a family named Xu; he calls the father of the family Uncle Xu in the Han language. When we visited them several times in 1993, the father (a Han) and most of the children always spoke with us in Han, while the mother, a Prmi, spoke Nuosu. I assumed the father did not speak any Nuosu, but Ma just laughed at me. “He won’t speak it with me or people around here who know Han, but he can speak it perfectly well when he has to deal with Nuosu from the mountains.” In another instance, I heard a Mr. Chen, the team leader of Lianhe, joking with some Nuosu friends in the Nuosu language; he then used Nuosu to offer me a cigarette. When Nuosu and Prmi converse, they may speak either Han or Nuosu according to the context and the individual abilities of the speakers; nobody in and around the town who is not Prmi or Naxi knows more than a few isolated words of Prmi.

In the village of Changma, about an hour-and-a-half walk northwest from the town, the population is about half Nuosu and half Prmi, and the local schoolteacher there told us that by the time children are of school age, they all can speak both Prmi and Nuosu, and some have already picked up a fair smattering of Han, which makes teaching easier.

In Yangjuan Village, by contrast, where everybody is Nuosu, people of the older generations are less likely to know Han fluently. Many men sixty and over in Yangjuan know a little Han; when I speak with them we get by in a mixture if nobody truly bilingual is in attendance. Ma’s father’s elder sister (1919–98), did not speak more than a few words of Han, and this is probably typical for the elder generation of women there. In addition, children ordinarily do not learn much of the Han language until they are of school age; if they do not go to school, they still tend to pick it up in town, sometimes with explicit instruction from their families. Ma tells stories of not understanding much of what the teacher said in the first few years of school, and teachers in the Baiwu elementary school confirm that you have to be able to speak Nuosu if you are going to teach first or second grade, since you at least have to give instructions in Nuosu, even though the lessons themselves are in Han.

There are, in this kind of mixed linguistic situation, mutual influences between the two languages. Here as elsewhere, Nuosu has borrowed a lot of Han words, and Han speech has borrowed Tibeto-Burman syntactic and phonetic patterns: people often say, in Han, things such as “Fa[n] chile meiyou?” (lit., “Rice eaten not eaten?” or, “Have [you] eaten yet?”), which adopts the Tibeto-Burman subject-object-verb word order. Liangshan Han dialects in general, perhaps under the influence of Nuosu, which has no syllable-final consonants, have also converted their syllable-final n (and sometimes also ng) to a nasalized vowel, so that I was once told by a Nuosu entrepreneur, “Ngome yao fazha ngomedi jingji, yao duo mai pigu,” which means “If we’re going to develop our economy, we need to sell more apples,” but sounds, in standard Chinese, like “. . . we need to sell more backsides.” And Han of all ages, including those who speak no Nuosu, universally use the Nuosu exclamation of surprise, “Abbe!” instead of the “Aiya!” common in other dialects of Mandarin.

In official contexts, language appears in a great variety of mixtures. Most government documents are in Han (though some forms for filling out, and most government signs, are usually bilingual), and there is still very limited opportunity for the use of Nuosu writing in official contexts. But spoken language is another matter, as illustrated by the speeches given in a packed, fluorescently lighted room by government dignitaries at the grand ceremony celebrating the connection of the town to the electrical grid in 1993. The first speaker was Sha Decai, a Nuosu and head of the township government. He spoke entirely in Han, as did the next speaker, the former Party secretary of the now-defunct qu, or district. Then Township Head Sha introduced the highest ranking dignitary, Vice-Secretary Yang of the County Party Committee, a Nuosu, who spoke almost entirely in that language, inserting here and there a Han vocabulary item. He was followed by another vice-secretary, a Han named Chen, who apparently knew no Nuosu and spoke in Chongqing dialect, somewhat different from Liangshan Han speech, but still readily comprehensible to much of the audience. Once he had introduced these high-ranking officials, Township Head Sha seemed to relax a bit, for he used Nuosu to introduce the next speaker, a Mr. Li from the county electric company, a Nuosu from Yanyuan who has traveled all over China and even to Singapore. Mr. Li spoke a complete jumble of the two languages, but even when he was in the Nuosu sentence-mode, he used a lot of Han phrases, such as guahao jianshe (grasp construction), dianshi ji (television set), lao baixing (common people), the numbers for the prices of electric power, and the titles of government officials and organizations. A local Party cadre then spoke in Nuosu, Vice-Secretary Chen again in Han, and then finally the head of the county People’s Consultative Conference (an office that, in Liangshan, would always be held by a member of an ethnic minority), gave another speech in which he switched, seemingly randomly, between the two languages.

It is difficult to understand this public use of Nuosu and Han languages in terms of the usual theories of code-switching, in which people in polyglossic situations switch from one language or variety to another according to the situation, the interlocutors, and the topic (Heller 1988: 6). Here the situation was the same for everyone, the audience also remained constant, and the topics all had to do with the benefits of electricity for economic development. What does seem clear is that many Nuosu cadres are, on the one hand, accustomed to the Han language governmental idiom used to speak of such phenomena as economic and infrastructural development. On the other hand, all of them unfailingly are saturated with ethnic pride and ethnic identity, and want to speak their own language when they can, especially to a Nuosu audience. These contradictory forces pull upon them whenever they are in their official role, and they thus code-switch without regard to context or content.

The names of the Nuosu cadres, however, tell us immediately that they come from a mixed area where the influence of the Han language is pervasive. All the Nuosu lineages in this area carry one-syllable, Han-type surnames, which are used in school, in official life, and any other time they are speaking the Han language. The local branches of the Loho clan, for example, carry a Han surname pronounced Hu in standard Chinese, but locally pronounced Fu. The Mgebbus are Mas (thus Mgebbu Lunzy is Ma Erzi, his father Mgebbu Axshy is Ma Ashi, and his nephew Mgebbu Vihly, head of the county animal husbandry bureau, is Ma Wei’er); the Hiesses are Lis, the Lamas are Mas (Mgebbu and Lama, both quho clans, can intermarry, even though their Han surnames are both Ma). Members of different local lineages of the same clan often carry different Han surnames as well (Shama Qubi is locally Sha, Ma, Qu, Qiu, Bai, or Bi), and of course several different surnames are shared by members of several ethnic groups; Prmi tend to be surnamed Yang, Dong, or Xiong, and Yang is also a common Han surname for Nuosu, and of course for the Han themselves.

This situation contrasts sharply to that in Mishi and other parts of the Liangshan nuclear area. There Nuosu clan names are simply transliterated into Chinese characters, so that for example Hielie becomes Hailai, Shama remains Shama, and Alur becomes A’er. In the nuclear areas, even the Han language preserves the original clan names; there the Han language must adapt itself to local reality, which is ethnically entirely Nuosu. In Yanyuan, by contrast, Han-language surnames are part of a common idiom shared by all ethnic groups in the area, but they do not necessarily conform to the kinship systems of the ethnic groups that use them.

Also in contrast to Mishi, the primarily Han-language educational system in Baiwu has produced a large number of graduates who have gone on to higher schooling and full participation in the larger Chinese society of Liangshan and beyond. Many of the Lohos, who left the area after the democratic reforms, are prominent in educational circles in Yanyuan and elsewhere, but the greatest achievement among the local clans has belonged to the Mgebbus. This is perhaps because the Lohos and Mgebbus had a head start on Han language education even before the Communist takeover. During the Republican era, it had become clear to political leaders in Liangshan, partly under the influence of the tusi and Whampoa Military Academy graduate Leng Guangdian, that the future lay in some sort of accommodation with Chinese society and political power, and the leaders of the Loho clan in Baiwu became part of this movement. In 1943 one of them went to Xichang and met a young man named Wu, a scholarly boy from central Sichuan, who was not able to go to middle school because of his family’s poverty. The Lohos offered him long-term employment; he lived in the house of one of the Loho leaders, and in return for room and board taught a sishu, a traditional private school where local boys learned the Confucian classics. All of the students in the sishu were from the Loho and their retainer clans, including several from the Mgebbu.

Later on, Mr. Wu was succeeded by a Mr. Yuan, and after the democratic reforms, Teacher Yuan stayed in the village and settled down, but the sishu was abolished and replaced by an elementary school in 1956; many of the current county political leaders were students in the first few classes. Mgebbu students did well there also, and there have up until the present been ten college students from the Mgebbus of Yangjuan, studying at places such as Central Nationalities University, Southwest Nationalities Institute, Southwest Financial and Economic College, Liangshan University, and, most remarkably, the Central Music Conservatory in Beijing, where one young man in 1993 was completing a degree in vocal performance; he sang Verdi as part of the entertainment at a Nuosu village wedding.4

Baiwu and the neighboring township of Dalin now boast both a six-year complete elementary school and a three-year middle school in Baiwu Town, as well as twelve other elementary schools, ranging from one to six years. Enrollment in the Baiwu middle school (which, like its counterpart in Mishi, is never the first choice for graduates of the elementary school) was higher in 1994 than at any time since it became possible for elementary graduates to go elsewhere; there were 100 students in four classes. Similarly, the elementary school was bursting at the seams; 659 students in 14 classes were its largest enrollment ever. But even with the increased commitment to education in the past few years, there remains a large gender imbalance in both schools. In the middle school, just 18 of 95 Nuosu students were girls (as contrasted to 9 of 18 Han and Prmi students), and in the regular, Han language classes of the elementary school, only 143 out of 440 Nuosu students (and 10 of 28 Han and Prmi students) were female. It appeared that education, while increasingly common among boys, still failed to reach very many girls.

It is thus extremely interesting what happened when, in the spring of 1994, the principal of the Baiwu elementary school decided to organize a class to be taught primarily in the Nuosu (Yi) language. The regular classes, like those in Mishi, teach written Nuosu only as a single subject, and starting only in the third grade. But the “Yi-language class,” the first to be recruited since 1984, would use the Nuosu language to teach all subjects except Han language and literature. Word went out to the villages, and the place was mobbed with registrants; 117 children signed up for the Yi language class and, reluctant to turn anyone away, the principal recruited another teacher (with no state salary available, the second teacher had to be minban, or paid for out of local tuition and fees). The most notable thing about the registrants, however, is that they were mostly girls—sixty, as opposed to fifty-one boys, in contrast to twenty girls and forty boys in that year’s first-grade Han-language class—and that many of them were in their middle or even late teens.

The Baiwu elementary school first-grade classroom in fall 1994 thus presented the odd but inspiring spectacle of little first-grade age children in the front rows, backed up by fully-grown young adult women and a few adult men as well. The teenage students have exchanged their skirts and headcloths for ordinary trousers and bright-colored scarves, but they still stand out in a situation where no Han girl would wear a scarf, and they appear very intent and serious about the first-grade lessons. Ma Erzi and I tried to interview the students about their experience, but they were embarrassed and we were mobbed by younger students coming to look at the foreigner, so we could only ask a few basic questions of the students, and we talked to several of the teachers (all local Nuosu) about what had happened.

When the call went out for students to register for the Yi-language class, apparently teenage girls in several surrounding villages got together and talked about the possibility of starting school, even at their relatively advanced ages. They did not want to go through life illiterate, but had previously felt daunted by having to study in a language with which they felt insufficiently familiar. So they came in groups; in almost every case, there was more than one teenage student from a particular village. Many parents supported the girls’ decision initially, but others opposed it, and some girls surreptitiously took Sichuan peppercorns from their families’ harvest and sold them in the market to be able to pay for tuition and books. One twenty-four-year-old woman, already married but not yet living with her husband, who came was taken back home by her father, who did not want her to jeopardize the marriage.

In the school statistics, there are very few first-graders listed as being of advanced age. This is, according to the teachers, because the teenagers simply gave their ages as much younger than the actual figures, in order not to stand out among their classmates. When we interviewed them, several women who appeared fully grown and adult gave their ages as 12 or 13, plausible perhaps in the protein-rich American suburbs, but extremely unlikely for Nuosu in Liangshan.

It is difficult to predict how long this trend of Nuosu-language education for female students might last. Certainly the obstacles are formidable, not the least of them the fact that someone who starts at seventeen will not even finish elementary school until twenty-two, by which age almost all women are married. And there is no possibility of skipping grades, since there are no higher-level Yi-language classes as yet, though this of course may change. For this reason, one young teacher persuaded his nineteen-year-old first-grade sister to transfer to the Han-language class, where she could move faster, and of course offered her help, something that would not be available to most of the teenage girls. In 1996 she was in the sixth grade. But the eagerness of these teenagers to get a Nuosu-language education, even an elementary one, speaks against the stereotype of conservatism and indifference to modern change often leveled at the Nuosu. In Baiwu at least, what women seem to feel uncomfortable with is not modern education, but Han-language education, and it is quite possible that if Nuosu-language primary education is expanded, the schooling and literacy rates for women in places like Baiwu will increase dramatically in the coming years.5

KINSHIP AND CULTURE AS DEFINERS OF ETHNIC IDENTITY

Baiwu is like many other places I have visited, where Nuosu as an ethnic group are defined not only by their history, as recounted briefly above, but also by their common kinship and by cultural markers of ethnic distinctiveness.

Charles Keyes, in a now-classic article (1976) has pointed to belief in common descent as an important defining characteristic of ethnic groups, and certainly this is true both literally and metaphorically for Nuosu in Baiwu. Everyone’s primary identity is a clan identity, and that clan identity indicates not only ethnicity but also caste membership; there are no more nuoho since the Lohos moved out, but there are quho and mgajie, and the barriers are strict between them. These barriers are maintained not only by genealogical recitation, which enforces the stories of common descent, but also by strict caste endogamy; not only descent but also affinity is an important aspect of kinship that binds members of a caste together. In our survey of over two hundred marriages, we found only two between quho and mgajie, and one more between quho and nuoho.

Almost as strong as the marital barrier between castes is the prohibition on intermarriage with other ethnic groups. Our survey recorded five marriages between Nuosu and other ethnic groups in Baiwu; two of these have involved high-school educated Nuosu and Prmi or Naze who have met in a partially de-ethnicized urban context. There have, however, also been three interethnic marriages between villagers, two of which took place before the Communist takeover. One was a legitimate arranged marriage between a Mgebbu woman and a member of a Naze family; another involved a Prmi from Changma Village who was captured as a slave in a raid by the Lohos; he was sold to Zhaojue in the nuclear area, where he married another slave of his owner, whom he brought back to the Baiwu area after the Democratic Reforms. The slave castes of the Nuosu were long replenished by marriage with captured Han, so this marriage does not fall outside of traditional Nuosu norms. Since the democratic reforms, there has been only one Nuosu-Han marriage among villagers; apparently a young Han woman who worked in a store in Baiwu town simply fell in love with a Nuosu from Lamata who often traded at her store; they now live in Lianhe (where mixed ethnicity is common), but their children are classified as Yi, in order to take advantage of affirmative action policies.

Nuosu practice of ethnic endogamy in Baiwu is typical of ethnically mixed areas I have visited in various parts of Liangshan. Places like Mishi, of course, are not at issue; there is nobody else to marry unless you are a shameless social climber. But in Gaoping, Yanbian, for example, the first Nuosu community where I lived, I first heard the sayings that “Yi and Han are two separate families” (Yizu Hanzu shi liang jia) and “Water buffaloes get it on with water buffaloes; oxen get it on with oxen” (Shuiniu shuiniu guo; huangniu huangniu guo), referring to the structuralist equation, universal in Liangshan, of Han with water buffaloes and Nuosu with oxen.6 (In some places, such as Baiwu, where there are a lot of Prmi, associated with Tibetan culture and classified as Zang, they enter the equation as a third element—yaks, or maoniu.) And in Gaoping, there was only one recorded intermarriage, an urban-generated one between a Han schoolteacher and a Nuosu former county cadre. The situation was the same in Puwei and Malong in Miyi, as well as in Gaizu and its environs near Lugu Lake, and in Hema Township in Ganluo. Whatever other relations Nuosu have with different ethnic groups, friendly or hostile or a combination of the two, they do not intermarry.

At the same time, it is possible to use similar metaphors about animals to deliver a different message. More than once I have heard cadres, eager to promote the government line of harmony among minzu (minzu tuanjie), say that, well, water buffaloes are water buffaloes, oxen are oxen, but they are all cattle (shuiniu shi shuiniu, huangniu shi huangniu, buguo dou shi niu).

Common descent and endogamy are one group of the signs of ethnic solidarity and distinctiveness among the Nuosu; the other consists of those cultural features known as ethnic markers (Keyes 1996). The most salient of these are dress, architecture, and ritual.

Nuosu women’s dress stands out in places like Baiwu as the single most visible sign of ethnic group membership and identity. Young women wear a “hundred pleated,” ankle-length, full skirt, which in this area has a black border around the hem, two broad horizontal bands of bright colors in the middle, and a wine-red, unpleated band at the top. Jackets are usually sleeveless, with intricate embroidered and inlaid patterns of colored thread, and these days as often as not worn over store-bought blouses. An intricately embroidered head cloth is secured by means of long braids tied over it; in cold weather, plaid scarves may also be added. Colorful wooden beads are often complemented by fine silver rings and earrings. In the wintertime, women, like men, may also wear the felt jieshy and/or the woven woolen vala with the long fringe around the hem.

Nuosu women in other areas vary this outfit; indeed one can tell, with a little practice, not only the age and marital status of a woman (married women with children wear a black headcloth, and older ladies favor subdued colors) but her county and sometimes township of residence from her dress. Women from Gaoping in Yanbian, in the Suondi (southern) dialect area, for example, have a distinctive particolored band in the lower-middle part of the skirt, and when they are young wear a diamond-shaped, black cap secured with a red ribbon or yarn. When they grow older, they wear a floral-patterned towel as a headcloth. In Guabie in 1994, many young women wore artificial flowers in their headdresses. But there is never any overlap between the dress of Nuosu women and that of other groups; any woman dressed like this (or any man or woman wearing a vala) can immediately be identified as Nuosu.7

Still, as with the animal metaphors, there is room here for ethnic coalition-building. Twice I have paid visits in a Nuosu friend’s company to wedding or holiday gatherings in Prmi or Naze houses and been greeted with the saying that “everyone who wears skirts [and metonymically, this includes their menfolk as well] is one family” (fanshi chuan qunzide dou shi yi jia or nbo ggasu cyvi nge). This refers, of course, to the fact that minorities’ ethnic clothing always includes skirts, while Han women wear pants.

Architectural differences are more subtle than sartorial ones, at least on the outside; in Baiwu it is difficult to tell a Nuosu from a Han house at a distance. When one approaches more closely, however, there is an important clue: Han houses have red paper couplets (duilian) pasted over their courtyard gates and the doors to their public rooms; Nuosu houses do not. On the inside, the houses are arranged differently. Han have an altar on the back wall of the main room, facing the doorway, at which they worship heaven, earth, country, the ancestors, and the local spirit Tudi Ye. If they have a hearth, it is simply a fireplace in the floor along the right-hand wall as one enters the house; they cook on mud or brick stoves in the kitchen. The public area of the front room is walled off from bedrooms, kitchens, and other rooms to either side.

FIG. 10. A family seated around the hearth, waiting for dinner. The family head at the right is a school principal.

Nuosu houses have much less distinction between public and private space. In Baiwu (and Yanyuan generally) the hearth is right in the middle of the floor as one enters the main doorway; it serves as fireplace as well as cookstove (fig. 10); water can be heated in a kettle hanging from the roof-beams, while food can be cooked in pots or woks balanced on the three hearthstones or andirons, or, if the fare as usual is nothing but potatoes, you can just put them in the coals and take them out and eat them when they are done. Nuosu also have a spirit-altar, but it is a high shelf in the right-hand corner as one comes in the door. There are sometimes separate bedrooms in such a house, but it is rare these days that there is not also a bed or two in the main room, sleeping on beds having replaced the earlier practice of just spreading capes as bedrolls around the fire.

Ritual is the final area in which culture serves as a marker of Nuosu identity. Nuosu celebrate a different series of holidays from the Han. Despite the recent promotion, in the regional minzu discourse, of the Fire Festival on the twenty-fourth day of the sixth lunar month as the quintessential Yi holiday, this day is in fact celebrated by many ethnic groups, minority and Han, all over the Southwest. But the Nuosu do not celebrate the important Chinese holidays of Yuanxiao (fifteenth of the first lunar month), Qingming (April 5), Duanwu (fifth of the fifth lunar month), and Zhongqiu (fifteenth of the eighth) and they have only a rudimentary celebration of the Chinese New Year. Instead, Nuosu have their own New Year celebration, called Kurshy, which comes at various times in the late fall and early winter, differing from year to year and according to the area. Nuosu in Baiwu are, of course, glad for the festive atmosphere around the Chinese New Year, and Nuosu teenagers certainly set off enough firecrackers all over the town on New Year’s Eve in 1993, but ritual is minimum; as was pointed out to me the next day, “Han celebrate the New Year, Nuosu play basketball” (Hanzu guo nian, Yizu da qiu).

More important than the yearly calendar are the rites of passage, marriages and funerals the most prominent among them. In a Nuosu wedding, like its Han counterpart, a bride is transferred to her husband’s house and family, but the similarities end there. A Nuosu bride is visited by her husband’s relatives before the wedding, and members of the two families splash each other with water during the evening’s festivities. The next day, she comes to her husband’s village with her male relatives (in Baiwu, some female relatives also come along, but this is not a universal practice), and they are greeted first by people from her husband’s clan who serve them liquor, cigarettes, and candy outside the village, where they wait until the sun goes down, when the bride is carried into her husband’s house on the back of a male cross-cousin of a clan other than her husband’s. The husband takes no part in any of these ceremonies, but they may spend the night together before she returns with her relatives to her natal home. Before the bride and her relatives leave, the husband’s relatives present them ritually with money and liquor to repay their effort in bringing the bride (fig. 9). She will visit increasingly frequently over the next few years, until, perhaps pregnant by this time, she finally moves in.

Funerals are also very different, for the simple reason that Nuosu cremate their dead (and thus, in this one single sphere of life, are uniformly judged by the government to be more progressive than their Han neighbors, who practice burial). A Nuosu funeral is a massive affair even for a poor village family; typically they slaughter several oxen and/or sheep, feeding several hundred people after the pyre is lit. At funerals as at weddings, young men from the clan of the deceased (and if the deceased is a woman, also from the clan into which she married) conduct song duels, chanting the glory of their clans and their exploits, while anyone who has hunting or militia rifles fires them off into the air at random. When the body is reduced to ashes, no grave is prepared, but the ashes are deposited on a nearby mountain, and the spirits worshipped at the domestic altar.

FIG. 11. Nuosu women’s clothing as ceremonial dress: at a wedding

This is not the place to go into the details of ritual symbolism at Nuosu weddings or funerals. The point is to demonstrate the extent to which these rituals are utterly unlike those of the neighboring Han (or, for that matter, of the other minzu either). The language of ethnic markers comes into sharp play in a place like Baiwu, where Nuosu are part of a local ethnic matrix. Unlike Mishi, where dress is deemphasized because there is little need to mark ethnicity, where housing is simply the style in which people have always lived, and where weddings and funerals are primarily ways of cementing and altering social relations within and between kinship groups, all of whom are Nuosu, in Baiwu these communicative acts take on a second and perhaps more important meaning. Nuosu clothing, houses, weddings, and funerals all occur in full view of neighbors who belong to Han, Prmi, and sometimes other ethnic groups (figs. 11–13). They attend each other’s ceremonies, visit each other’s houses, and observe each other on the street and in the fields dressed in particular ways. Together with language, stories of common descent, and practices of marital exclusivity, these practices mark off what it means to be Nuosu in a community where there are other possibilities.

FIG. 12. Nuosu women’s clothing as ethnic marker: dancing to celebrate electricity

What seems most interesting about the use, even the efflorescence, of ethnic markers in a mixed community like Baiwu is that culture is more emphasized as it comes into contact with other, contrasting cultures, in a kind of Batesonian schismogenesis (Bateson 1958 [1935]: 171–97). Differences in these areas are emphasized at a time when Nuosu have more opportunity to participate in education, bureaucracy, economic development, and other facets of the wider Chinese society. Having realized, beginning as early as the 1930s and 1940s, that a completely isolated, independent Nuosu muddi was no longer possible or perhaps even desirable, people have not taken the path of assimilation. They were partially forced in that direction during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, but as soon as the strictures were loosened in the early 1980s, they opted for conditional participation in the wider society—participation contingent on retaining a strict boundary in the spheres of family and certain aspects of culture while they participate in other, more cosmopolitan activities.

FIG. 13. Nuosu women’s clothing as everyday gear: building a road near Guabie

Nuosu in Yanyuan and other counties of Liangshan have not just reaffirmed their cultural distinctiveness as they have opted for participation in the wider society and economy. They have also attempted to turn the state programs of political integration and economic development toward local ends and purposes. When entrepreneurs who are heads of state-owned companies talk about Han invasion of their lands and exploitation of their resources, when intellectuals, some of them professors in Chinese universities, talk about the bandits of the 1950s as not being opposed to Communism, but only to the Han, we realize the complexity and contingency of participation in Chinese stateand nation-building practices. People will participate, and this already makes them very different from many outright ethnic nationalists in places such as Xinjiang and Tibet.8 After all, what country do Nuosu belong to, if not to China? But they will take full advantage of political “autonomy” and preferential policies in cadre appointment, school entrance, and planned birth, because they feel it is owed to them. There is risk in such participation, however, and one of the ways of buffering the risk is to strengthen the use of the Nuosu language in educational and political contexts, as well as reemphasizing the cultural markers of ethnic identity. Another way to buffer this risk is through psychological strengthening, which includes a reemphasis on the fact of ethnicity in many kinds of languages and conversation.

1. I treat the relationship between Buddhism, older priestly practices, and ethnicity among Prmi and Naze, as well as many of their other customs that serve as ethnic markers, in detail in chapters 10 and 11. Here the point is simply to delineate the place of these people in the ethno-history and ethnic relations of Baiwu.

2. It is always difficult to assign dates in Nuosu history, since the oral histories recited by members of different clans speak in terms of generations rather than years. This is the same problem encountered with the history of the Jjivo lacquerware makers (see chap. 6).

3. Some parts of this history of Baiwu are corroborated by more than one person; others are uncorroborated but fit. I am indebted to the following people for portions of the story: Mgebbu Lunzy (Ma Erzi) and his father Mgebbu Ashy (both originally from Yangjuan), Party Secretary Lama Muga (from Hongxing), Yanyuan local historian Loho Tuha (Hu Jin’ao) [the preceding all Nuosu], and Shu Maolin (Naxi), descendant of the bazongs of Baiwu.

4. The story of education in Baiwu, in particular the ethnic dimensions of school success, is treated in the most detail in Harrell and Ma 1999. A briefer analysis of the ethnic dimension is also given in chapter 15.

5. This may, in fact, happen in the next few years. Ma Erzi started, with overseas financial help, a model elementary school in Yangjuan Village, which opened in fall 2000. This school is taught bilingually and attempts to enroll equal numbers of girls and boys, as well as numbers of qunuo and mgajie proportional to their population.

6. In some places water buffaloes and oxen are replaced with goats for Han (because they sometimes grow beards) and sheep for Nuosu (because they traditionally did not grow beards).

7. The details of Nuosu dress, and the ways in which they express social status variables, including gender, marital status, age, and home area, are treated in detail in Harrell, Bamo, and Ma 2000.

8. There are, of course, plenty of Uygur and Tibetans who also participate in Chinese stateand nation-building processes. But there is much more direct opposition in those places than in Liangshan.