5 / Nuosu History and Culture

Nuosu are the largest, most culturally distinct, and most ethnically separate ethnic group in Liangshan, and their ethnic identity is thus the simplest to describe of all ethnic groups in the area. Nuosu are concentrated in most areas, scattered in a few; they speak four dialects that are fairly mutually intelligible, and their customs and costumes vary slightly. But all Nuosu are classified as Yi, and when they speak the Han language (as perhaps half of them can do), they identify themselves as Yi. Nuosu life is influenced by Han society and culture to varying degrees, to the point where members of some communities in what Chinese ethnologists call the “nuclear area” (fuxin diqu) rarely come into contact with Han people or culture, and then only in official governmental or educational contexts, while Nuosu people in parts of the Anning Valley retain only language and a few religious customs, along with a sometimes-violated rule of endogamy, to distinguish themselves from the surrounding, and numerically overwhelming, Han. But there are no communities where Nuosu cultural markers have disappeared altogether, and in fact no communities where the language has disappeared, either. Acculturation, that is, has never been anywhere near complete in Nuosu rural communities. Even in the cities, ethnic identity is strong, and many educated Nuosu make strong efforts to retain at least those elements of culture that will reinforce their identity. In other words, no matter what degree of acculturation to Han ways, there has been little or no assimilation to Han identity. For Nuosu, ethnicity is a primordial thing, in the sense that they are all related, not only by descent but also by marriage, and that non-Nuosu are not only descended from different ancestors but also are not related by marriage.1 For most Nuosu, ethnicity is also a cultural thing, but even where culture has been thinned by participation in Chinese urban society, the primordial, kin-based identity is never called into question. The case of the Nuosu is thus one in which all the languages of ethnohistory, ethnic group identification, and ethnic identity agree: they speak in different terms, but they come to the same conclusion: Nuosu are a primordially separate group.

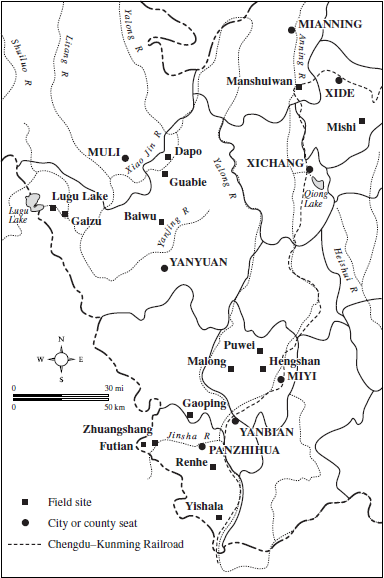

In this and the following chapters, I first give overviews of Nuosu history and culture, and then provide a detailed account of Nuosu kin-based identity in a variety of contexts, from the most cultural (that is, the areas where the differences between Nuosu and Hxiemga [Han] culture are the least blurred and taken the most for granted) to the least cultural (where even language starts to fade, exogamy is possible, and only genealogy and consciously maintained cultural traits preserve the sense of identity). I do this by means of detailed accounts of four contexts (three local and one diffuse) where I have lived and worked, along with evidence from similar communities elsewhere in Liangshan (see map 4).

In this analysis, Mishi represents the cultural pole of Nuosu primordial identity. In fact, one could probably come up with a more ideal community, somewhere in Meigu or the outer reaches of Zhaojue or Butuo, but the overwhelmingly Nuosu population, the dominance of the language, and the absence of Han influence except in government and schools mean that in Mishi life is Nuosu; only the outside, the threatening, the somewhat incomprehensible other, is Han.

Baiwu is culturally less pure. The population of the areas around the town is only around 80 percent Nuosu, with significant minorities of Prmi and Han. Almost everyone except a few older women speaks Han in addition to Nuosu; in the villages closer to town, and in the town market, Han people and culture are a fact of everyday life. But the language, customs, religion, and ritual of Nuosu in this area are little influenced by Han culture; if anything, the effect of the Han presence in this area is to sharpen the sense of identity and ethnic boundaries, while blurring the cultural differences between Nuosu and others only a little.

In the lowland village of Manshuiwan, Nuosu culture is superficially unrecognizable. Houses look like Han houses, and there are graves in the hills where ancestors have been buried. Many people are highly educated, having attended schools teaching only the Han language, and not everyone even has a Nuosu name; some people use their Han names even when speaking the Nuosu language. Remarkably, however, Nuosu ddoma endures as the preferred medium of everyday speech, and the ideal of endogamy is still articulated (though sometimes violated in practice). Here, where culture really is diluted and compromised, ethnic identity still seems a matter of course.

MAP 4. Field sites

Finally, among educated officials, teachers, and scholars, in Xichang, Panzhihua, and distant cities such as Chengdu and Beijing, even the language is unevenly distributed, and marriage with other minzu is quite common. But in these cities, where cultural difference is no longer an unexamined aspect of ethnic relations, identity with and dedication to the cause of ethnic solidarity remains strong, and many people consciously preserve cultural elements in the service of preserving ethnic identity and pride. Whereas in a place like Mishi identity follows culture in an unself-conscious way, in Xichang culture is self-consciously mobilized in the service of identity.

NUOSU HISTORY

Both Nuosu genealogical and ritual texts and Han-language historical documents trace the origins of the Ni (Yi) peoples to northeastern Yunnan around the time of the Han dynasty. Where they came from before that is in dispute, though a lot of people think they were either in the area for a very long time or came in the first millennium B.C.E. from somewhere in the Northwest, perhaps Qinghai, along with the other Tibeto-Burman peoples (Ma Changshou 1987, Chen Tianjun 1987). The Wuman (Black Barbarians) and Baiman (White Barbarians) mentioned in the histories of the Period of Division (311–589), as well as the Cuan kingdoms of the Sui-Tang period (581–907), are thought to have been ruled by the ancestors of today’s Yi, and at least one faction in an ongoing debate considers the Nanzhao kingdom, which ruled Yunnan and surrounding areas after 740, to have been a Yi-dominated polity (Qi Qingfu 1987). The descendants of the rulers and subjects of these and other kingdoms are said to constitute today’s Yi peoples, who numbered 6.6 million in the 1990 census, with about 4.1 million of those in Yunnan, 700,000 in Guizhou, and about 1.8 million in Sichuan (Zimei 1992: 1).2

Those Yi living in Sichuan belong to the cultural and dialect group that calls itself Nuosu, and almost all of them live in Liangshan Prefecture or a few surrounding counties; in addition, a hundred thousand or more Nuosu live in Ninglang and other counties in the part of western Liangshan that is in Yunnan. How and when the Ni peoples came into Liangshan is a matter of dispute; archaeological remains from the Han period in southern Liangshan seem to belong to some other ethnic group (Yi Mouyuan 1987: 303). Emperor Xuanzong (r. 713–56) of the Tang granted fiefs in the Anning Valley and at Yuexi to local lords who fought with the Tang against the Tufan, or proto-Tibetans, and later against the Nanzhao kingdom; these may have been ancestral to the Nuosu (Ma Changshou 1987: 101).

There is no doubt that by the Song dynasty (960–1279) Nuosu were firmly ensconced in the nuclear area of Liangshan, where they remain the overwhelming majority to this day. Their history since then has been one of keeping both the manifestations of Chinese power and the cultural influence of the Han at bay, while never forming an independent polity or even a society and culture completely free of Han influence. Nuosu people, while consciously preserving the distinct character of their culture and society, have always done so in a context that we can legitimately call ethnic; to be Nuosu is to be enmeshed in the outer webs of Chinese civilization, never truly independent but at the same time never succumbing, except selectively, to either the coercion or the blandishments of Chinese wealth and power, or of sinocentric cultural imperialism.

After the Mongols united China in the thirteenth century, including their conquest of Nanzhao in 1253, they established the tusi system of local rule that was to serve them and their successor dynasties and even the Republican government up to the Communist takeover of the area in the early 1950s. All over the Southwest, they enfeoffed local leaders as officers of the empire, giving them imperial seals and rights of local rule in return for the promise to be loyal and sometimes render various kinds of tribute. Liangshan was no exception to this policy. Members of the highest caste or stratum of Nuosu society, the nzymo (Wu Jingzhong 2001) were given various titles of tusi or the slightly lower offices of tumu, tuqianhu, and tubaihu. The most famous of these, enfeoffed during the early Ming dynasty, was the ruler known in Nuosu as the Lili Nzymo or, formally in Chinese, as Luoluosi Xuanweisi, or informally as the Lili Tusi. His headquarters were in what is now Meigu County, the heart of the nuclear area, and his nominal territory extended to the Dadu River on the west, the Jinsha River on the south, and into what is now Puge County on the southeast (Ma Changshou 1987: 106–7; Sichuan Sheng Bianji Zu 1987: 66–67). Other Nuosu tusi ruled in the more easterly and southerly parts of Liangshan.

According to tradition, sometime around the end of the Ming, the Lili Tusi’s power was overthrown by the Hma and Alur clans of the nuoho or aristocratic caste because his exactions upon them were too severe. He moved to Xihewan in Zhaojue, but his family was again forced out of the area by a nuoho alliance, and he fled all the way to the outskirts of Xichang sometime in the early Qing dynasty (Ma Changshou 1987: 109). Similarly, other Tusi were forced out of the nuclear area at various times during the Qing by the increasing power of the nuoho clans; the most powerful remaining tusi, the Shama Tusi of Zhaojue, was gradually forced to Leibo by 1890, and Hedong Changguansi of the Leng family was forced from Yuexi to Tianba in Ganluo, where the early twentieth-century scion of that house, Leng Guangdian, became famous as a promoter of modern education and economic development during the 1930s and 1940s.

At one level, this ongoing struggle between the nzymo and nuoho, the two highest castes of Nuosu society, was fought over rights to land, retainers, and slaves as well as over the disputed rights of rule that the nzymo had over the nuoho. But at another level, one can see a larger struggle being played out, with the nzymo, ever drawn by official seals, offices, and power into the orbit of the surrounding Han civilization and culture, playing the cosmopolitan role that tied Nuosu society to China, and the nuoho playing the conservative, xenophobic role and becoming impatient with the nzymo, who began to look like agents of the Chinese.

The tusi system endured in the Southwest throughout most of the Ming and early Qing, with new tusi families being enfeoffed in the Kangxi period in many areas, including the Naze families described in chapter 11. But there was a countermovement toward absorbing formerly semiautonomous fiefdoms into the regular bureaucratic structure of the ruling dynasties. This movement, called gaitu guiliu, or “replacing the local and restoring the posted [officials],” began in the late Ming in some areas, but in Liangshan and adjacent parts of Yunnan did not really get going until the Yongzheng period (1722–36), when the emperor originally resolved to get rid of all tusi and replace them with regular bureaucrats appointed from the center. He tried this in Liangshan, where several county yamen were built, and those at Jianchang (modern Xichang), Yuexi, Yanjing (modern Yanyuan), Mianning, and Huili all gradually evolved into counties that remain to the present day. Attempts in the nuclear area, however, were unsuccessful, provoking revolts by local Nuosu, and in 1776 the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–96), son of Yongzheng, gave up and created four new tusi who governed parts of the nuclear area, though some of them also lost out in battles with local nuoho clans (Yi Mouyuan 1987: 306; Sichuan Sheng Bianji Zu 1987: 1–3).

During the Qing period, however, nuoho clans did not fight only against local nzymo; they also fought each other for land, retainers, slaves, and honor. The battles were particularly noteworthy in Zhaojue and Puxiong, with the result that clans or clan branches defeated in these fights migrated first into Xide and Yuexi, where some remained while others continued across the Anning Valley into Mianning and the western parts of Xichang, and from there into Yanyuan, northern Yanbian, Ninglang, and Muli. They took with them many of their quho (commoner) retainers, with the result that the population of the latter areas is now 40–70 percent Nuosu, including a small number of nuoho and a much larger number of quho (Sichuan Sheng Bianji Zu 1987: 87–89).

At the end of the Qing and into the Republican period, then, most of the nuclear area was populated exclusively by Nuosu, and except for a few areas still under the control of tusi, there were no formal political organizations, only the informal leadership and customary law of the nuoho-dominated order. This order is reflected in a series of ethnographic reports compiled by Han scholars in the 1930s and 1940s, the best known of which, by Lin Yaohua, was translated by the Human Relations Area Files and published in English in 1962 as Lolo of Liangshan, despite the fact that Lin never used the demeaning term Lolo (Lin Yaohua 1961; see also Zeng Chaolun 1945 and Jiang Yingliang 1948). With increasing Han population pressure on the edges of the nuclear area, the nucleus itself became increasingly impenetrable by outsiders not under protection of local leaders, and large numbers of Han settlers, as well as a few Western missionaries and adventurers, were killed or captured into slavery during this era. At the same time, the peripheral areas were once again experiencing partial incorporation into the wider Chinese civilization, and such prominent figures as Yunnan governor Long Yun and educational reformer Leng Guangdian were among the Nuosu who participated actively in the politics of the early twentieth century.

The first meaningful contact with the Chinese Communists came when the Long March passed through Liangshan in April 1935, traveling from Huili to Dechang, Xichang, Mianning, Yuexi, and Ganluo, where the marchers made the famous crossing of the Dadu River described by Edgar Snow. Snow’s picture of Nuosu people was on the romantic side:

Moving rapidly northward from the Gold Sand River . . . into Sichuan, [the Red Army] soon entered the tribal country of warlike aborigines, the “White” and “Black” Lolos of Independent Lololand. Never conquered, never absorbed by the Chinese who dwelt all around them, the turbulent Lolos had for centuries occupied that densely forested and mountainous [land]. . . . The Lolos wanted to preserve their independence; Red policies favored autonomy for all the national minorities of China. The Lolos hated the Chinese because they had been oppressed by them; but there were “White” Chinese and “Red” Chinese, just as there were “White” Lolos and “Black” Lolos, and it was the White Chinese who had always slain and oppressed the Lolos. (Snow 1938: 195–95)

The parts of Liangshan through which the Red Army passed were of course not the nuclear area, and by the 1930s leaders of local Nuosu clans were well aware of the ins and outs of Chinese politics. But there was very little “underground Party” activity after the Red Army left again, until they came back as national rulers in 1950 and 1951.

Liangshan was made a Yi autonomous prefecture; originally it had Zhaojue as its capital and included only the nuclear area and surrounding counties east and north of the Anning Valley; the remainder of the current prefecture was part of Xichang Prefecture. In 1978 Xichang Prefecture was abolished and the capital of the new Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, which included all of its present counties, was moved to the more accessible Xichang. Whether this change was made in order to dilute Nuosu demographic dominance can probably never be known conclusively, but it did mean the incorporation of many more Han, Zang, and other minzu into the prefectural population. Panzhihua City was founded in 1965 as part of the Third Front internal industrialization program (Naughton 1988); in 1978 Miyi and Yanbian Counties were brought under Panzhihua’s administration (Dangdai Liangshan 1992: 10).

Specific policies of the Communists in the early period varied according to local conditions. In the Anning Valley and most other areas where Han settlement predominated, as well as in the Lipuo areas of Panzhihua and a few other areas where minority inhabitants were judged to have entered the historical stage of the landlord economy, or late feudalism, land reform was carried out in 1952–53, as it was in many Lipuo areas in Chuxiong (Diamant 1999). In the nuclear area and in high-mountain regions in Lesser Liangshan, the familiar pattern of putting cooperative traditional leaders into vice-posts was followed, and not until 1956 was there an attempt to transform the means of production. This went smoothly at first, as mentioned above, but after a radical turn of policy in 1957–58, many local leaders, some of them formerly officials in the Communist-led governments, organized a rebellion against the radical reforms that had deprived them not only of their wealth and power but, more important according to many Nuosu people, of their honor. As early as Leng Guangdian in the 1930s, they argue, Nuosu leaders knew the slavery system was doomed, but they refused to be treated with contempt, as in the struggle sessions so common to Chinese Communist political movements everywhere.

The rebels probably never posed a serious threat to centers of Communist rule or to the People’s Liberation Army, but they did control many villages during the two big outbreaks in 1957 and again in 1959. More rebels probably died of sickness and starvation than from PLA bullets, and many more were captured and executed or imprisoned and died of disease in prison. But the latest holdouts surrendered by the early 1960s, and there has been no significant rebellious activity since then, though there was a brief “caste war” between nuoho and quho during the Cultural Revolution in the nuclear area.3

During the 1950s considerable attention was paid to development in Liangshan. Roads, clinics, and schools were all built, and local people participated in the initiatives and unintended disasters of the Great Leap Forward; even remote villages in Mishi had collective mess halls. The ensuing famine was not as serious there as in some other places, though locally many people did die of hunger, as they did in another local famine in 1974. Also in the 1950s and 1960s, there was a movement for script reform, replacing the old syllabary with New Yi Writing, a phonemic script using the Roman alphabet. By all reports, it was a total failure.4

The Cultural Revolution everywhere saw an attempt to eliminate many aspects of ethnic minority culture, and Liangshan was no exception. All education was in the Han language, and religious activities were banned, though they of course continued in secret in many places. Everyone tells me, however, that Nuosu women continued to wear Nuosu clothing during this time; that was something that “could not be controlled.”

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, and especially since the passage of the Autonomy Law of 1982, the emphasis has come back to the promotion of those aspects of Nuosu culture that are deemed harmless according to a now more liberally interpreted Communist morality. This has meant the replacement of Han officials in most administrations with minorities, primarily Nuosu; the official promotion of ethnic “culture” in the form of arts and crafts, song and dance, and often lavish, officially sponsored holiday celebrations; and the return of Nuosu language to education, this time in the form of a “regularized Yi writing” (guifan Yiwen), which is the old script used by religious practitioners, rationalized and cleaned of phonetic redundancy. Religious practitioners once again practice relatively freely, and in general it is difficult to tell what sorts of cultural practices—other than the old economic practices of slavery and other kinds of unfree tenure—are prohibited, and what others are judged innocuous and therefore allowed.

Liangshan is still one of the poorest prefectures in all of China (Heberer 2001), and grand schemes of development have left many, perhaps the majority, of Nuosu villages almost entirely untouched by such modern amenities as electricity, piped water, roads, clinics, organized recreation, and schools that go beyond the first or second grade. But the standard of living is rising in many areas, and more important for this study, the field is open for the assertion of ethnicity, short of political demands for actual autonomy. In this atmosphere, Nuosu culture and ethnic identity are once again important parts of people’s lives.

NUOSU CULTURE AND SOCIETY

As is evident from the brief history recounted above, Nuosu society and culture have for a long time developed in conjunction with, or perhaps in opposition to, but never in ignorance of, the larger and more cosmopolitan culture of China. This means that certain characteristics are shared in common but are given a distinctive twist in each culture; the same elements are used one way by the Hxiemga and another by the Nuosu. This might be metonymically represented by the calendrical system of naming years, months, and days after twelve animals—Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Chicken, Dog, and Pig. The years represented by each of these animals are the same for the Han and the Nuosu, but the months are backward—for Nuosu the counting of months begins with Rat in the seventh month of the Chinese calendar, so that a melancholy Nuosu pop song intoning, “Go softly in the month of the Tiger” (Lahle tego iessa iessa bbo)—approximately October—is given the translated Han title “Bie zai jin qiu,” meaning “Parting in the Golden Autumn.” Many aspects of Nuosu culture and society are of this sort, looking similar to their Han counterparts on the outside, but carrying very different inner meanings, while others have no such resonance, standing instead in stark contrast to the corresponding aspects among the Han.

Clan, Marriage, and Kinship

The core of Nuosu society is the patrilineal clan, or cyvi.5 When two Nuosu strangers meet, they immediately ascertain each other’s clan and place of residence, asking, “Whose son are you?” (Ne xi sse nge?) of a man, or “Whose daughter are you?” (Ne xi mo nge?) of a woman, and also “Where do you live?” (Ne ka isu nge?). To be a member of Nuosu society, one must have a clan identity. Clans all have genealogies, which people learn to recite; some nzymo and nuoho, as well as bimo (priests), who always come from quho clans, can recite sixty or more generations of ancestors, while most quho, other than bimo, can spiel off ten to thirty generations. Nuosu customary law is based on the differential obligations of people of the same clan and different clans. For example, the penalties paid for murder or other lesser forms of homicide differentiate between killings within and outside the clan (Qubi and Ma 2001). Members of a clan are also expected to help each other out, in precedence to other people. When I was living in Mishi, there was a murder of a traveling merchant, who was not closely related or well acquainted with any local residents. Once it was determined, however, that he was a member of the Shama Qubi clan (one of the largest quho clans in Liangshan), local representatives of that clan (none of whom had known him personally before) took up a collection to enable the deceased’s wife and children to purchase several animals to sacrifice and serve to guests at his funeral.

The local politics of prerevolutionary times were primarily those of intermarriage, feuding, and alliance among clans. The great nuoho wars of the late eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries, mentioned above, are examples of this, but so are local clan feuds between, for example, the Mgebbu and Qumo clans around Baiwu. After a Mgebbu woman married into the Qumo clan sometime in the 1930s and was mistreated, there was feuding and a prohibition on marriage between the two clans that has basically lasted to this day; no Mgebbu in our sample of over one hundred marriages was married to a Qumo, despite the fact that they live only an hour or two’s walk away.

Clans are also strictly exogamous, meaning that marriage between clans serves as a means of making alliances and creating ties of kinship among their members. This can be seen even at a casual level. I was sitting waiting for dinner in a little restaurant in Gaizu, near Lugu Lake, with my collaborator Vurryr and our driver Alur, both members of the Mgebbu clan. In walked a stranger, who spoke to the proprietor in Chinese, and a few minutes later Alur and the newcomer realized that both were Nuosu. When they did, they naturally asked each other’s clans. The newcomer immediately told Alur that their two clans were affines (which, in a practical sense, probably simply meant that they both were quho), so he should call Alur onyi, or “mother’s brother” (since the stranger was considerably younger), and he insisted on finding a chicken to sacrifice for the happy occasion. We already had noodles on the fire and finally talked him out of it, but this little incident is an indication of the depth of clan consciousness in everyday life. More generally, intermarriage among clans creates both strong local alliances, as repeated marriages to cross-cousins thicken the web of local kinship, so leaders of local lineages pay constant attention to marriage arrangements even today. Intermarriage also creates a more general net where most nuoho or quho clans are related to most others of the same caste (not to speak of the nzymo, who are very few anyway and thus limited in their choice of marriage partners), and thus call each other by affinal kin terms.

The practice of cross-cousin marriage is also reflected in the Nuosu system of kin terminology. In an ideal bilateral exchange, ego’s mother’s brother marries ego’s father’s sister, and mother’s sister is often married to father’s brother. Thus there are only six kinds of relatives in the senior generation: father (ada), mother (amo), father’s brother or mother’s sister’s husband (pavu), mother’s sister or father’s brother’s wife (monyi), mother’s brother or father’s sister’s husband (onyi), and father’s sister or mother’s brother’s wife (abo). For a man, the female cross-cousin (assa) is a potential spouse and thus a joking partner, as is the male cross-cousin (onyisse) for a woman. By no means all marriages are arranged with cross-cousins, so that the father’s sister, for example, is not always the mother’s brother’s wife. But conceptually, the two categories are the same.6

The Nuosu emphasis on clan as a human matrix of social organization contrasts with the Han emphasis on attachment to place. There are immediate and absolute bonds of attachment between two clan-mates that override either local or affinal ties, and for many people these extend clear across Liangshan. In addition, whether it stems from a past of nomadic herding or swidden agriculture, or from a lack of territorially based government, there is a lack of attachment to place when compared to Han culture. The histories of nzymo dynasties and nuoho and quho clans alike are histories of migration; even rites for the soul of the deceased send it through a progression of places that reverses the migration, so that everyone ends up in the same place, unlike the Chinese underworld where one can be found by a bureaucratic address containing province, county, and village (Ahern 1972: 232). This is also reflected in a lack of attention to housing and environment in many places. Certainly Nuosu culture is famous for extolling the beauty of certain kinds of environments,7 but the attachment to particular places is much weaker than the attachment to clans, and even the architecturally most interesting of houses are rarely built to endure or be passed down through the generations. Old people, who live separately from their sons in most cases, usually get some sort of little shack built for them; soon they will die and the house will be knocked down, and chances are their sons will move on anyway. In these conditions, the idea of a local community with continuity on the land does not arise; in its place there is the idea of the clan whose ties of solidarity transcend locality.

Caste and Class

Liangshan Yi society is famous in China because Chinese ethnologists have determined that it is one of the few remaining examples on earth of slave society, which according to Morgan, Engels, and Marx, came between the stages of primitive and feudal society. There are a great number of articles and books about this particular, concrete manifestation of a historical stage, and there is a Museum of Liangshan Yi Slave Society on a hill outside Xichang. As a consequence of this, Marxist writers in the 1950s and early 1980s tried to correlate the endogamous strata of nzymo, nuoho, quho, mgajie, and gaxy with places in a system of cruel and exploitative relations of slaveholding. More recent writers, however, have separated the two concepts, much as writers on India have long recognized that caste and class coexist and overlap, but do not coincide, in any particular village order (Mandelbaum 1970: 210–11).

The caste order of the Nuosu is best explained as the woof of the fabric whose warp is the clan system. Every clan is ambiguously nzymo, nuoho, or quho; members of the lowest strata have no clan affiliation and are thus liable to be held as slaves or serfs by members of clans of any stratum, including their own (Pan Wenchao 1987: 324).8 One never asks the caste of a new acquaintance, but one does ask the clan, and unless it is a clan unrepresented in the local area, or occasionally one with a name similar to that of another clan of a different caste, one knows immediately the caste of the interlocutor. The most important factor that separates one caste from another is endogamy. Nuoho virtually never marry quho, on penalty of expulsion from the clan, and it is rare that quho, unless their own clan identity is suspect (in Nuosu, their “bones are not hard”) marry members of the lower order. Nzymo ordinarily do not marry nuoho either, but in recent years there have been some marriages simply because of the difficulty of finding a spouse from the rarefied nzymo stratum, whose members are usually considered to have constituted only a fraction of 1 percent of the Nuosu population. Prohibitions on intermarriage are still taken very seriously today. Lin Yaohua (1993) recounts a series of cases from the nuclear area in the late 1980s and early 1990s in which nuoho clans either prevented marriages with quho or severely punished their members for going through with the marriage. I once asked a nuoho friend, a highly educated man completely at home in the Chinese scholarly world, what he would do if his daughter, then about fourteen, were to want to marry a quho. He said he would oppose it. I asked him if this were not an old-fashioned attitude. He admitted that it was, but gave two explanations. First, he said, he just wouldn’t feel right inside. More important, other nuoho might boycott his family for marrying out, and they would thenceforth have trouble marrying within the nuoho caste. This had happened to some of his affinal relatives in another county.

It is important to point out at the same time, however, that caste stratification in Liangshan has never, as far as I can tell, included notions of pollution or automatic deference, which are so important in the Indian caste system. In areas where there are both nuoho and quho, they socialize freely with one another, eating at each other’s houses and often becoming close friends. None of this, however, breaks down the marriage barrier; only among highly educated urbanites is intermarriage ever considered, and then it is usually decided against; most nuoho would rather have their daughters marry a Hxiemga than a quho.

The economics of the relationships between strata disappeared with the Democratic Reforms, but much retrospective research allows us to reconstruct a picture of what they were like. In the nuclear area, at least, class stratification was based primarily on personal labor and tribute obligations on the one hand, and slaveholding on the other. Not every stratum was represented in every area. For example, in Leibo around the headquarters of the Shama Tusi, there were no nuoho, and quho retainers were immediately subordinate to the nzymo, paying rent for land they held but having the right to buy and sell those land rights among themselves. Other quho were farmers on the nzymo’s own land, serfs who owed labor to the lord but also had their own allocated plots to raise their own subsistence crops. The independent quho farmers, as well as the nzymo families, could hold slaves belonging to the lower castes, who themselves were divided into several different orders, the higher of which could hold slaves from the lower orders. Slaves could be bought and sold among any strata who held them (Sichuan Bianji Zu 1987: 18–19).

The more common situation was probably one where there were nuoho but no nzymo, and often a large number of quho of one or more clans would be considered the retainers (called baixing in Han) of the nuoho lords. They owed small amounts of tribute and labor, as well as allegiance to the lords in fights, but they themselves often became quite wealthy, and the richest of them, like their nuoho lords, were also slave owners. A quho who was impoverished or unable to pay a debt might become a slave, but a nuoho could never become a slave of anyone, only a poor, ridiculous, fallen aristocrat.

The actual status of slaves has been a matter of some contention. Hu Qingjun (1981: 200) made the remark, infuriating to many Nuosu scholars, that the gaxy, or household slaves, were nothing but “tools that could talk,” hui shuohua de gongju. Many Nuosu scholars dispute this analysis, and—while acknowledging that slaves were often captured in raids on other clans or, more often, on Han farmers in the peripheral areas, or when people ventured into Nuosu communities without adequate guarantees—also stress that customary law required that slaves be treated with some respect, and that although they could be ordered, they could not freely be insulted or maltreated without cause (Ma Erzi 1993). Certainly prerevolutionary analyses by Han scholars often opined that the life of a Nuosu slave was better than that of a poor Han peasant (Lin Yaohua 1961 [1947], Zeng Chaolun 1945); this opinion was no longer allowed once the Marxist idea of the place of slave society in human history became official dogma, since the assumption was that once humanity left its primitive condition, things were at their worst in slave society and became progressively better in manorial feudalism, landlord feudalism, capitalism, and socialism—a series of invidious comparisons that Marx probably would have laughed at, but that also indicates the involvement of the Nuosu with Chinese society, even in the understanding of their own institutions.

Specialist Social Statuses

Nuosu society, even leaving aside the obvious Chinese connections in the institutions of nzymo or tusi, was far from a homogeneous mass of farmers, landlords, and agricultural slaves. Several kinds of specialist social statuses were, and in some cases still are, important to the construction of society. Other than nzymo, the most important of these are suga, or wealthy person; ndeggu, or mediator; ssakuo, or military leader; gemo, or craft specialist; bimo, or priest; and sunyi, or shaman.

There is a Nuosu saying that “suga is the head of splendor, ndeggu is the waist of splendor, and ssakuo is the feet of splendor” (Ma Erzi 1992: 105). Ma explains this as meaning that in the prerevolutionary society of old Liangshan, with no officially recognized political statuses or offices (except for the occasional tusi), people stood out for their accomplishments and abilities in different fields. As in many societies, someone who could command wealth (in land, livestock, and/or slaves) was automatically prominent, and someone who was wealthy enough could move, for example, from a status of mgajie to that of qunuo, or the top stratum of the quho caste, whereas someone of a quho station who was poor could descend into slavery, and even a nuoho who was poor was a no-account.

The contrast between political position in Han and Nuosu society is revealed in another proverb: “In Han districts, officials are the greatest; in Yi districts, ndeggu are the greatest.” “Judge” is an awkward translation of the title “ndeggu”; literally, it means a person who can cure evils, in this case the evils of crime and disputing (Ma Erzi 1992: 99). Ma Erzi describes the attributes of the ndeggu as follows: “wise in counsel, able to resolve disputes in Yi society, sharp at analyzing questions, decisive in using words to persuade people” (ibid.). There was no formal title, no initiation ceremony, no insignia of office for a ndeggu; there were only reputation and results. A ndeggu was simply someone (male or female, nuoho or quho or even mgajie) who could be called upon to settle questions and adjudicate disputes. But in a society with no formal political office, these people with the ability to interpret customary law and persuade others to make their decisions stick were granted the highest respect.

Little has been written about the status of the ssakuo, or brave warrior, but Nuosu traditional culture valued bravery as much as wealth or political and judicial wisdom. Liu Yu’s characterization of Nuosu society as resembling the heroic age of Homeric Greece captures, I think, a bit of this flavor (2001). She quotes a series of proverbs that will have to serve here, in the absence of more detailed ethnography, to convey the flavor of the idea of bravery in Nuosu culture:

One thinks not of thrift when entertaining a guest; one thinks not of one’s life when fighting or killing enemies.

No one makes way when wrestling; no one flees when caught in a hold.

There is no boy who does not wish to be brave; there is no girl who does not wish to be beautiful.

When one climbs high cliffs one does not fear vultures; on the battlefield one does not fear sacrifice.

Nuosu society also produced a variety of crafts and craft specialists. Known collectively as ge or gemo, “people of skill,” they include blacksmiths, who make rounds from village to village producing agricultural and craft tools; silver- and goldsmiths, who produce jewelry and decorations for the wealthy; and the producers of the painted tableware (see chap. 7) that, in the revival of ethnic culture in the 1980s and 1990s, again is to be found in every house, from remote villages to the mansions of the elite in Xichang and other major cities.

Perhaps the most specialized occupation of all in Nuosu society, however, is that of the priest, or bimo. Bimo are always male (legend has it that a famous bimo tried to train his daughter as a successor, but she was found out by her two pierced ears, since men pierce only the left ear) and almost always are quho, usually from a few prominent clans, in which the knowledge is passed down from father to son; among the most famous of these are the Jjike, Shama Qubi, Ddisse, and Jili (Bamo 1994: 216). To become a bimo requires a long period of apprenticeship, and typically a father trains his sons, or if no sons are available or if they don’t show the requisite abilities, perhaps other agnatic relatives or occasionally nonrelatives, who however must pay a stiff fee and cannot inherit all the ritual knowledge of the teacher (Bamo 1994: 215–26; 2001; Jjike 1990).

The life of a bimo centers around texts and rituals. Although Nuosu writing was used at various times in history for various political and administrative purposes, before the twentieth century the skills of literacy were almost exclusively in the hands of the bimo, whose books include rituals for a wide variety of purposes, from curing illness to success in war or politics to harming an enemy to the all-important funerary ritual of cobi, the so called “indicating the road” to the soul of the deceased back through all the places its ancestors had lived to the original home of the Ni (in Qinghai?) and thence to the heavenly regions.

Finally, in addition to the bimo, there is another kind of religious practitioner, the sunyi. Sunyi can be male or female, can come from any caste, and respond to inspiration rather than to heredity or apprenticeship. They become possessed by and drive out spirits, entering trance and displaying their spirit power by fire-eating and other feats, using drums and chants to cure and to exorcise. Little research has been done on the sunyi.

Family and Gender

Descent and inheritance in Nuosu society are of course patrilineal, and gender ideology values males as superior to females, but this is one more way in which superficial similarities between Nuosu and Han culture hide deeper contrasts. Perhaps most important, the relationship between generations in Nuosu society is more affectionate and not so hierarchical or authoritarian as that among the Han. As in most cultures, there is a cult of motherhood; a recent pop song about missing mother brings tears to the eyes of educated or village Nuosu who hear it on boom boxes or play it on car and bus tape decks, and folktales and folksongs emphasize the affection people have for their mothers.

In Han culture, this affection for the mother is balanced by a distant and authoritative relationship with the father, especially on the part of his sons, but Nuosu father-son relationships are not nearly so stern or one-sided. Even in peasant families, father and son often discuss issues of large and small import by the hour around the fire, contrasting with the almost total lack of communication between father and son in many Han peasant families (Yang 1945: 57–58). Sons do not live with their parents after their wives move in permanently several years after marriage, but set up separate housing, sometimes in the same compound but sometimes in distant parts of a village or cluster of houses. A man with adult sons can count on a minimum amount of support, but he has very little authority over them unless he is prominent locally within the lineage. For most practical purposes, then, a local lineage consists of agnatically related adult men, each of whom is the head of an independent nuclear household; there is no level of extended family household or property-based corporate segment between the household and the body politic of the lineage itself. People are closer to their own brothers and near cousins than to more distant relatives, but there are no corporate lineage segments.

Gender in traditional society is a difficult topic to get at. It is clear that gender differentiation and homosociality are a feature of Nuosu social interaction—all one has to do is to look at the people huddled on a hillside at a wedding or funeral, with knots of men here and knots of women there. The elaboration of gender in dress, adornment, and folklore is also extreme. At the same time, however, there are hints that gender roles in prerevolutionary society were sometimes fluid. There are stories (not folktales but recent reminiscences) of female ndeggu and even ssakuo, and prerevolutionary ethnologists, both Chinese and foreign, always compare favorably the position of Nuosu women to that of their foot- and housebound Han counterparts (von Eickstedt 1944: 168; Lin Yaohua 1994 [1947]: 47, 58).

It thus seems a bit paradoxical to me that, if anything, the status of Nuosu women in village society today shows greater differences from that of men in terms of their participation in contemporary public society and culture. We found, for example, in Baiwu that whereas Nuosu males were on the average better-educated than Han and Prmi males, Nuosu women had the least schooling. Village and township schools, in fact, typically have only a small minority of girl students. Very few Nuosu women become cadres or teachers, again in contrast to Han and, particularly, in my impression, to Prmi and Tibetans. In everyday interaction, around the fire in the home, women serve men, eat after them, and do most of the housework while men sit, talking and drinking. On the other hand, indulgence in psychoactive substances is not a male prerogative as it is among Han; almost all Nuosu women smoke and drink heavily. In conversation, the genders are mutually respectful, and women’s opinions are listened to when offered but are not offered as often or as assertively as those of men.9

In the field of ethnology itself (to get really self-referential about this), however, the situation again seems somewhat egalitarian. There are a large number of Nuosu women professors, and so far all but one of the Ph.D. candidates of Nuosu extraction, whether from Chinese, American, or French universities, have been women. The disjunction between the retiring role of women in village life and their prominent participation in at least one aspect of wider culture awaits further research and analysis.

Language, Writing, and Literacy

The Nuosu language belongs, according to Chinese linguists, to the Yi sub-branch of the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan family; other languages in this branch are Lisu, Lahu, Hani, Jinuo, and Bai (Guojia Minwei 1981: 585). Yi is in turn divided into six “dialects” (fangyan), with Nuosu constituting the Northern dialect. This classification, however, is politically determined by the results of the ethnic identification project; none of these “languages” is a single idiom or even has a single standard variety. A more linguistically based classification is that of David Bradley, who places four of the six “dialects” of Yi as delineated by the Chinese linguists into the Northern Branch of Yi (formerly Loloish); he places the Central and Western Yi dialects in the Central Branch, along with Lisu, Lahu, and some dialects of Hani (Bradley 1990, 2001). Like almost all Tibeto-Burman languages (Matisoff 1991), Nuosu is tonal, with tones serving a grammatical as well as a semantic function.

Unlike many Yi dialects from Yunnan, Nuosu has not in any manner given way to Chinese in the daily speech of Nuosu people. One hears the language not only on the streets and in the villages, but also in recordings, radio programs (though no television as yet), and official speeches at various levels of government. In addition, Nuosu has for at least seven hundred years been a written language. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the syllabic writing system, which seems to be completely independent of any other known script except for similar Yi scripts written in Yunnan and Guizhou, was almost exclusively the property of the bimo, who transmitted hand-copied ritual texts from generation to generation. In the mid-twentieth century, elite families in various parts of Liangshan began to use the script for secular purposes such as writing letters.

As mentioned above, a Romanized script failed to take hold during the 1950s, but in the late 1970s and 1980s a reformed version of the traditional script was promulgated and promoted and is now widely used for various purposes in Liangshan. School classes either teach in Chinese with Yi as a second language, usually starting in the third grade, or teach primarily in Yi with Chinese as a second language, usually starting from the first grade. There are standard textbooks for language and history all the way through senior high school, and texts for other subjects such as mathematics and sciences are being developed. I have watched elementary math classes taught in Nuosu, and it seems to excite the interest of the children much more than the equivalent material taught in Han, a language with which most of the children have to struggle. There is a provincial Yi-language school, or yiwen xuexiao, whose graduates often go on to Yi language and literature departments at Liangshan University in Xichang, Southwest Nationalities Institute in Chengdu, or Central Nationalities University in Beijing.

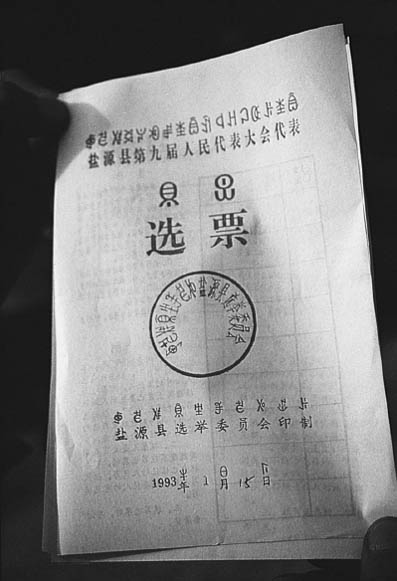

A commitment to using a language such as Nuosu as a second official language of public life means the development of a whole set of bureaucratic institutions of translation. Every county in Liangshan, as well as the prefectural government itself, has a language committee, or yuwei, whose task it is to translate government directives, forms, and reports from one language to another. Since most of the bureaucrats, even those of Nuosu ethnicity, find it more natural to write on administrative topics in Chinese, most of the translation is into Nuosu. It is not a meaningless exercise, however. For example, when I was working in Mishi, there was a cholera epidemic in nearby Zhaojue. Notices about cholera and what to do about it were posted in both languages on government bulletin boards. Similarly, the election ballots for the vote I observed in Baiwu were printed in both Han and Nuosu (fig. 3).

The problems of using Nuosu for bureaucratic communication go deeper than just habits, however. Until recently, the written (and spoken) Nuosu language did not deal with topics of modern technical or social innovations. In many places such as Baiwu, where nearly everyone has at least a rudimentary speaking knowledge of Han, this is customarily dealt with by inserting Han words into Nuosu conversation. Such terms as xuexiao (school), yidian (one o’clock), and qiche (motor vehicle) slip easily into Nuosu speech. The language authorities, however, feel it necessary to construct Nuosu equivalents for such words. This has produced calques for some terms, such as ssodde (studying place) for “school” and teku cyma (time one-count) for “one o’clock.” For other terms, Han words are borrowed but with a Nuosu pronunciation, such as guojie for “country” and “government” (from the Chinese guojia), and fizhy for airplane (from the Chinese feiji). Once, out of curiosity, I looked in the massive Han-Yi Dictionary published by the Sichuan Nationalities Press and found not only “nuclear power plant” and of course “proletarian dictatorship,” but, more surprisingly, “whale,” translated as jihxe, a half-calque of Chinese jing (whale) and Nuosu hxe (fish) (Hopni Ddopssix 1989).

These examples demonstrate the most salient fact about Nuosu culture: it exists to a large extent by absorbing things from, adapting things out of, and inventing things in reaction to the larger, more socially complex, and more powerful Han culture with which it is surrounded. Ethnicity in Liangshan must thus be understood primarily in terms of kinship, rather than culture. This does not mean that there are no circumstantial factors encouraging Nuosu ethnicity; obviously there are economic, political, and educational benefits to being a minority in Reform Era China. What it does mean is that Nuosu people themselves understand ethnicity in primordial terms. They do not see it as contingent in any way. It is always, in every situation, abundantly clear who is Nuosu and who is not; there is no blurring or contextual shifting of boundaries (see also Schoenhals n.d.). In many places culture, as well as descent, is the thing that makes some people Nuosu and others Hxiemga. In these places Han culture is either resisted entirely (as in Mishi) or selectively practiced while its importance is denied (as in Baiwu). In Manshuiwan, Han culture has mostly been taken over, but with no blurring effect on ethnic boundaries. Finally, in the cities, people whose basic, habitual practices are mostly Han consciously practice and display various aspects of Nuosu culture as a means of maintaining ethnicity. The following case studies will illustrate this continuum from cultural and ethnic separateness to cultural connection, and from ethnic separateness to ethnic identity as a reason for re-creating aspects of a separate culture.

FIG. 3. A ballot for a local election in Baiwu, printed in Nuosu and Chinese

1. In fact, the sense of kinship relations determining ethnic status is so strong that it was the justification for the former practice of slavery and even for the caste system itself. Those of lower status, while still related to their social superiors, are less pure in their ancestry (many of them being descendants of captives from other ethnic groups). See Schoenhals 2001.

2. There are also about ten thousand Yi in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

3. As far as I know, there are no published or publicly distributed sources that discuss this caste fight; I have heard of it from several Nuosu scholars. Apparently some young quho, imbued with the Red Guard spirit, attacked local nuoho, whom they considered unreformed backward elements, and nuoho fought back with militia of their own, after which the PLA intervened on the side of the quho, but quickly quelled the violence on both sides. My impression is that mortality was much lower than in the late-1950s rebellion.

4. This New Yi Writing, however, is the basis for the standard romanization system used in elementary school textbooks, and also to transcribe Nuosu words in this study. The Nuosu language has no syllable-final consonants, so the t, x, and p written at the end of syllables are used to indicate high, medium-high rising, and low falling tones respectively; syllables with no tone marker are in the mid-level tone. For ease of pronunciation for the average reader, we have eliminated the tone markers in this book.

5. Hill and Diehl (2001) claim that the cyvi is best understood as a patrilineage. We have a friendly argument over this; my conception is that the local representatives of a cyvi are much like a patrilineage but that the conception of a cyvi as a kin group extending throughout Liangshan, with descent not necessarily readily traceable among branches, is a classic example of a clan. I use “clan” to refer to the cyvi as a whole, while sometimes employing “lineage” to talk about the local organization.

6. For more detailed analyses of cross-cousin marriage and kin terminology, see Lin Yaohua 1994: 27–37; Harrell 1989; and Lu Hui 2001.

7. Ma Erzi (2001) recites a song describing life in an ideal environment:

We come to raise sheep on the mountains behind our house;

The sheep are like massed clouds.

We come to the plains in front of our door to grow grain;

The piles of grain are like mountains.

We come to the stream to the side of the house to catch fish;

The fish are like piles of firewood.

8. The relationship between caste and class in the lower orders of society is a matter of some contention. The strata known as mgajie and gaxy are defined primarily by their economic position—mgajie as serfs and gaxy as household slaves—but many people think of these as caste ranks as well, making the caste hierarchy nzymo, nuoho, quho, mgajie, gaxy. This view is strengthened by the fact that quho ordinarily will not marry mgajie. This kind of phenomenon, in which an occupational or economic status carries over into the exogamic hierarchy, is a feature that the Liangshan caste system holds in common with the jati manifestation of the Indian caste system.

9. Hill and Diehl (2001) report the same impression.