4 / The Land and Its History

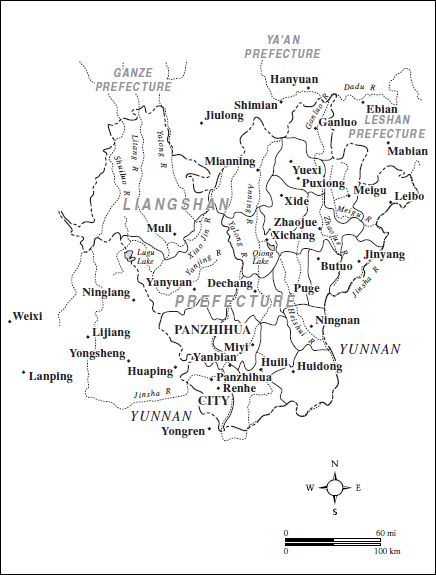

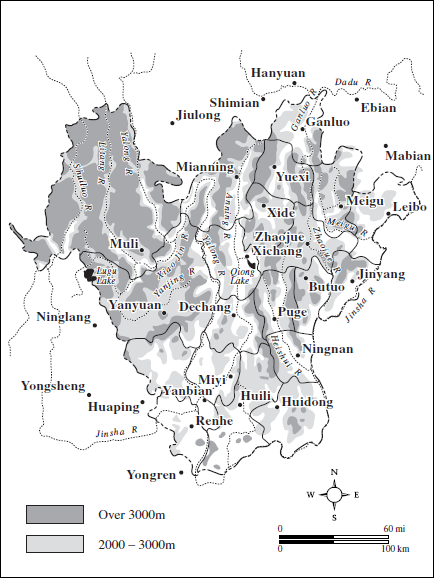

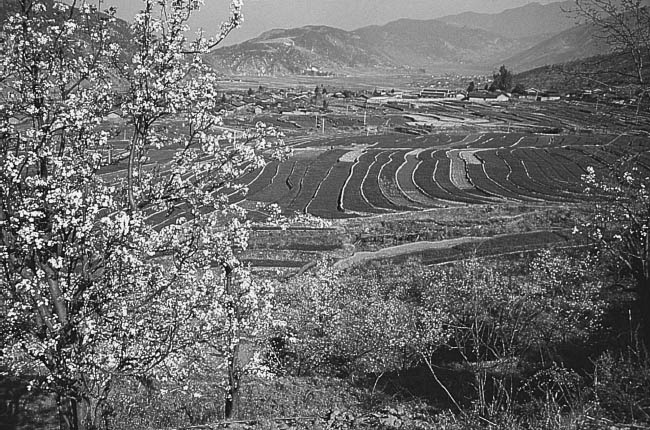

The Liangshan-Panzhihua area (map 1) forms an inverted triangle jutting down below the fertile plains of historic Sichuan on the north and northeast, between the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau on the southwest, south, and east, and the foothills of the Tibetan Massif on the northwest. It is a region of high, narrow ranges cut by the deep, steep-sided valleys of great rivers (fig. 1) and bisected by the wider, fertile rift valley in which flows the Anning River (map 2). The Anning Valley has an elevation of 1,550 meters at Xichang and only 900 meters at Panzhihua, and is characterized by mild, dry winters, scorching, dry early summers, and a rainy, warm season in late summer and early fall. Double-cropping is possible in the Anning River floodplain and in some of the lower-elevation small valleys and foothills. Where the land is reasonably flat, there are two agricultural seasons: the early, dry spring (xiaochun) season is used for wheat or barley (opium was formerly grown at this time), and the wetter, late or summer (dachun) season allows wet-rice cultivation (fig. 2). On slopes too steep for terracing, corn is grown instead of rice in the summer. The mid-level mountain areas, such as central Yanyuan, which lies at an altitude of 2,400–2,600 meters, have approximately the same yearly distribution of rainfall, most of it falling in late summer and early fall, but they are colder; they have no spring growing season, and only on the very warmest fringes can rice be grown during the summer. Otherwise, potatoes, corn, buckwheat, and oats are the main crops. In the winter, the weather in the mountains is usually dry, but it snows a few times every year, and the temperature drops well below freezing at night, though the high altitude brings brief warmth on sunny afternoons. In some of the great, deep river valleys such as those of the Jinsha (Upper Yangzi), Yalong, and Xiao Jin Rivers, the steep slopes next to the rivers are parched and covered with scrub vegetation; only when one rises a few hundred meters above the rivers is rainfall sufficient for cultivation. These rivers run cold and clear during the winter but turn into great brown torrents of mud during the rainy season. Valley-bottom alluvial soils tend to be yellow or brown, but many of the hills are bright orange or dark red, strongly contrasting with the small, spindly pines that grow there after larger trees have all been cut at least once. At higher mountain elevations of 2,500–3,500 meters or so, there are still considerable forests remaining, especially in Muli and other counties on the western extreme of the area. Systematic logging, which has already denuded the middle elevations, worked on these higher regions at least until the logging ban imposed in late 1997; it is unclear whether this ban is enforceable enough to allow the forests to grow again. On the highest mountaintops, well above 3,000 meters, forest gives way to grasslands, and there is considerable pastoral economy, involving mostly yaks, goats, and sheep, though cattle and horses thrive in the lower regions of the grasslands.

MAP 1. Liangshan and environs

FIG. 1. The valley of the Yalong River, between Xichang and Yanyuan

Transport has always been difficult in the Liangshan-Panzhihua area. The only railroad is the Chengdu-Kunming Line, which was built at great expense of money and lives in the late 1960s, finally opening in 1972. There are places where the track, in order to gain or lose elevation, doubles back upon itself in a series of loops and curlicues, and along most of the route a passenger on the train gets the distinct sensation that he is inside tunnels more often than he is out. Since the late 1980s, a few paved highways have been built; there is a good highway grid within the urban sections of Panzhihua, which is strung out over a fifty-kilometer length along the Jinsha River, and from Panzhihua north to Xichang and Lugu the road is paved and very serviceable, though it turns into dirt as it heads toward Yuexi and Ganluo. Side roads are more problematic; all the county seats have motor roads, but some, such as the one from Xichang to Yanyuan and on to Muli, are more like American logging roads than American highways. Many but not all township government headquarters are reached by dirt motor roads: the famous Zemulong, the most remote township in Panzhihua, had a road built in the late 1980s at great expense and effort; the road was open for eight hours before a landslide closed it, and it was still not reopened by 1998. Muli, the most remote county, has no paved highways, and probably less than half its townships are motor-accessible. In most counties there are a few townships to which one still has to walk, meaning that the old trade of muleteer is still not gone in Liangshan.

MAP 2. Liangshan in relief

FIG. 2. A fertile plain at Puwei in Miyi. The spring wheat crops occupy the terrace as fruit trees are in flower in March.

Outside the Anning Valley and the larger plains, or bazi, only a few villages—mostly those that happen to be on a road going somewhere else—can be reached by car. Bicycles, ubiquitous on country roads in China proper, are rare here because of the steepness of even the motor roads, and only a few motorcycles have yet made their appearance, most of them in the towns and cities, since almost all villagers are too poor to buy them. People occasionally ride horses, but mostly they walk—to the fields, to market, to visit friends. The trails to most villages are steep, rocky, and often slippery with mud, and mud is the construction material for village houses in most places; in the areas to the west, bordering on the Tibetan foothills, where logging was possible at least until recently, many houses are made of wood, often in log-cabin style, and Prmi houses in Muli are built partly of stone, as are Nuosu houses in Ganluo near the Dadu River, where stone is abundant. Only in the commercializing areas near the big cities of Panzhihua and Xichang are any village houses built of brick or concrete.

Building materials differ by area, but house plans and styles differ mainly by ethnic group. On the whole, Han live mostly in the lowlands and foothills, though there are some Han families in very remote areas. Similarly, Nuosu are mostly in the mountains, but some live on the plains, including several places on the Anning plain near Xichang. Lipuo in the southern part of the area live in foothills and low mountains. Prmi and Naze are confined to the deep valleys and high plains of the western part of Liangshan and on over into Yunnan, while Lisu and Miao live in scattered enclaves, usually in high and relatively remote places. Most mountain townships in western Liangshan have ethnically mixed populations; some villages within these townships are ethnically pure and others are mixed. In the Anning Valley and some of the surrounding foothills, there are many areas whose population is entirely Han, while the core of eastern Liangshan is almost completely Nuosu. Often in a particular area, ethnic groups are arranged roughly by elevation, giving an interesting tilt to the idea of social stratification in what has been called a vertical society, or liti shehui.

The area where I conducted my field research thus contains a large number of different ethnic groups, whether we define these groups in the formal languages of ethnohistory and ethnic identification, or whether we explore them in more detail by examining their interactions through the everyday languages of ethnic identity. This chapter first takes the former, formal route of definition, examining from the standpoint of ethnohistory, and then from the standpoint of ethnic identification, the names, brief histories, and locations of most of the ethnic groups in the area. The following chapters examine in detail the ethnic interactions and ethnic identities of three kinds of people, each of which uses all the available languages in communicating about its ethnic identity, but uses them in very different ways.

AN ETHNOHISTORICAL VIEW

It is not clear who inhabited the Lesser Liangshan area in the pre-Imperial period (before the second century B.C.E.), but in the chapter “Barbarians of Zuodu” (Zuodu yi zhuan) in The History of the Later Han Dynasty (Hou Han shu), there is mention of a kingdom of Bailang in this area, whose king sent ambassadors to the Han court in Luoyang and some of whose songs were recorded by the court historians. Ethnolinguistic analysis by Chen Zongxiang (Chen and Deng 1979, 1991: 4) and others has suggested that the language recorded (in Chinese characters, of course) in that account is related to the modern Qiangic languages spoken by the Xifan, or Prmi, people in this area. If so, the Prmi can claim to be, if not the original inhabitants, at least the earliest ones who are still there.

Better established is the fact that the language spoken by today’s Prmi people is one of perhaps twelve or so languages belonging to the Qiangic subfamily of Tibeto-Burman (Matisoff 1991) and that the other languages of this small subfamily are distributed along what is probably a historical migration corridor from the Qinghai or northeastern Tibet area south through the series of deep, north-south river valleys that parallel the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau (see map 2). This seems to indicate that speakers of this group of languages migrated southward along this route, culminating in the Prmi, who are the southernmost Qiangic speakers.

The Naze, who are also early inhabitants of this area, likewise claim a northwestern origin, and may have come along the same route as the Prmi, or may have entered from the Southwest, where the Naze and their close linguistic relatives the Naxi initially established small chiefdoms during the mid-Tang dynasty (618–907), which continued during the period of the hegemony of the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms, from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries (Shih 2000; Li Shaoming 1986). Naze and Prmi have lived intermingled in this area for hundreds of years and intermarry freely in many areas.

To the east, in the valley of the Anning River, there has long been Han settlement. This river valley and the surrounding foothills furnished the Shu Han general Zhuge Liang with the route of his “southern march” undertaken in the mid-third century C.E. as part of the three-way war between Han (or Shu), Wu, and Wei, immortalized in the great vernacular novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi). It is not clear exactly where he went, but he did establish administrative outposts in the area (Li Fanggui 1987). Nor is it clear when the earliest Han settlers entered Yanyuan and Yanbian, but they have certainly been a presence since the Yuan dynasty, if not before.

The Dali kingdom fell to the invading Mongols in 1253, and Prmi troops were reportedly instrumental in the Mongols’ victory in the Lesser Liangshan area (Shih 2000). When the Ming expelled the Mongols from this area in the late fourteenth century, they founded about ten local administrations (tusi), essentially establishing local rulers as agents of the Chinese state (Fu 1982: 135–36), whose sway extended throughout Yanbian, Yanyuan, and part of what is now Muli, as well as enfeoffing the Naxi tusi, or local ruler, at Lijiang and the Naze ruler at Yongning near Lugu Lake. Han settlement in such towns as Lijiang, Yanyuan, Yanbian, and Mianning and in their surrounding river valleys, also increased during and after the Mongol and Ming conquests.

In the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries, Tibetan Buddhism began to spread into the Lesser Liangshan area. Monasteries of the Red, or Karma-pa sect, were established as early as the late sixteenth century (Rock 1948, 1: 204–10), and the Gelug-pa, or orthodox Yellow sect, which assumed the government of Tibet in 1642 (Goldstein 1989: 1), also began to build monasteries and to convert the population of Prmi and Naze peoples beginning soon afterward (Shih 2000). The monk-ruler of Muli, whose kingdom was established at the beginning of the Gelug-pa ascendancy over Tibet, spread his administration into what is now northern Yanyuan, and most of the Prmi-speaking people under his rule appear to have converted to the Gelug-pa sect during the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. He was made a local official tusi of the Qing dynasty in 1729 (Fu 1983: 138), but it is unlikely that this changed his local political position or the ethnic composition of his domain.

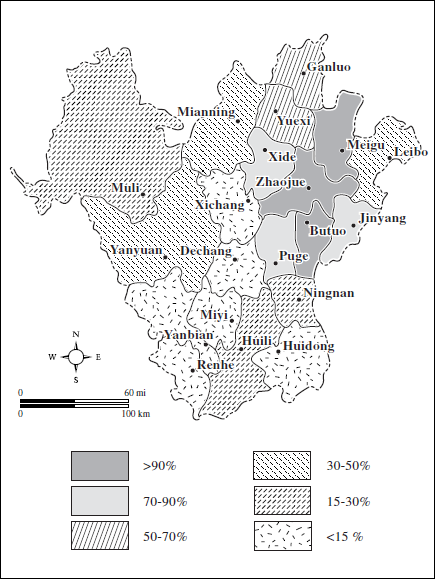

Speakers of Yi languages, which belong to a different branch of Tibeto-Burman (Matisoff 1991), have been established in eastern Liangshan at least since the Tang dynasty (Ma Changshou 1985: 102) and appear to have entered western Liangshan in three waves. The first Ming emperor, Taizu, in order to consolidate his rule over the area after his defeat of the Mongols in the 1370s, also supported the establishment of local rulers near Xichang in the Anning Valley, as well as in Dechang and at Puwei in Miyi. All of them came from northwestern Guizhou or northeastern Yunnan and spoke languages of the Nasu group, a subgroup of the Northern Branch of Yi (Bradley 1990), or the eastern dialect, according to the official classification. Meanwhile, the Nuosu, or Liangshan Yi, maintained a basically tribal existence1 in Greater Liangshan well into the twentieth century, with Han civilization encroaching only around the frontiers of what came to be known in the West as “Independent Lololand.” They continue to be the great majority of the population in the core counties of Greater Liangshan: in Xide County, site of one of the Nuosu villages covered in this study, Nuosu are over 80 percent of the population, and virtually 100 percent outside the river valley that contains the county seat, and they are over 90 percent in Zhaojue, Meigu, and Butuo, and 75 percent in Puge (see map 3).2 But because of intertribal warfare in eastern Liangshan (Sichuan Sheng Bianji Zu 1987: 87–89; see chap. 6, this volume), perhaps brought on by population pressure, Nuosu began in the mid-Qing to cross the Anning River and settle in western Liangshan as well. This mass population migration continued into the mid-twentieth century, and Nuosu now constitute a majority of the population in Ninglang, over 40 percent in Yanyuan, and substantial minorities in Yanbian, Muli, Mianning, and Miyi. In the process of this migration, Nuosu have displaced Prmi and perhaps Naze people in the peripheral areas of all these counties; it is unclear whether they have also displaced Han populations. Other Yi, related to people in central Yunnan and speaking dialects of the Central Branch of Yi, who call themselves Lipuo, have lived in counties to the southwest, in Yunnan province, at least since the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644); the population of my first-ever fieldsite, Yishala, is 92 percent Lipuo. Today’s Lipuo appear to be the descendants of Han troops, who entered the area during the early Ming, and local populations with whom they intermarried. Lipuo people have also come into the southern part of the Lesser Liangshan area in small numbers since the 1950s. In addition, there are pockets of Yi-speakers known as Yala, Shuitian, and Tazhi, whose origins and linguistic affiliations remain to be researched (see chap. 13).

MAP 3. Percentage of Nuosu population by county (Liangshan Prefecture and Panzhihua City)

Finally, there are enclaves of Lisu in Dechang, Miyi, Yanbian, and Yanyuan, as well as Miao populations in Yanbian and Muli. Most of them are recent immigrants; some were settled here by the Qing government in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries after being involved in disturbances in other parts of the country (Ye and Ma 1984: 111, 129).

The history of the migration of peoples in this area is thus exceedingly complex, and the resulting mix on the ground of local jurisdictions, languages, customs, and marriage alliances is as complicated spatially as it is temporally. Nevertheless, using the language of ethnohistory, it is possible to divide the current inhabitants into five sorts of people.

First, there are the early-resident groups of western Liangshan, who were the basis of the tusi political system of the area from the Mongol conquest until the twentieth century. A few of these are Yi (such as the Nasu tusi at Puwei), but most are either Qiangic- or Naxi/Naze-speakers. By the nineteenth century, many but not all of these people were adherents of one or another sect of Tibetan Buddhism, and many had picked up other Tibetan customs such as drinking yak-butter tea and barley beer. The influence of Tibetan civilization in this area, while rather late historically, is thus nevertheless profound.

Second, there are the Nuosu. They have long resided in eastern Liangshan but are among the latest of arrivals in the western area. Because of the massive numbers of their migrations, however, they now form a demographic plurality in most parts of western Liangshan as well. They have been remarkably resistant to acculturationist and especially to assimilationist pressures from Han or Tibetan civilization.

Third, there are little groups living in isolated enclaves. Three of these—the Miao, Lisu, and Tai—maintain relatively sharp ethnic boundaries, while others, mostly speakers of Yi languages other than Nuosu, are highly acculturated to Han customs and in some cases are becoming assimilated to Han identity.

Fourth are the Han themselves, people living on the most remote fringes of the world’s largest civilization. They are a majority in the lowland areas of the Anning Valley and of course in the major cities of Xichang and Panzhihua, and a minority locally in many parts of the region, but everywhere attached by descent and culture to the billion-strong mass of Han Chinese. They include both peasants, who have been migrating here for many centuries, and educators and administrators who have come since the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949.

Finally there are the Hui, or Muslim Chinese (Gladney 1991), who live primarily in the towns and cities and are descendants of a network of traders that has been in Liangshan at least since Sayyid Ajall Shams ad-Dîn, governor of Yunnan from 1275 to 1281, recruited a large number of Muslim laborers to work on road building and irrigation projects (Peng Deyuan et al. 1992: 99). There are also a few rural Hui communities in lowland areas of Xichang and Miyi. In urban communities and concentrated rural settlements, they actively maintain an ethnic identity and their Islamic religious practices; in smaller towns they are rapidly becoming assimilated to the Han population.

TODAY’S MINZU

The project of ethnic identification (described in chap. 3) produced a map of the peoples of Lesser Liangshan that is drawn in a different language, based on the results of that particular project rather than on scholarly research in general. Because this map is drawn entirely in the categories of the fifty-six recognized minzu, which sometimes do and sometimes do not coincide with ethnohistorical and linguistic divisions, it is somewhat at odds with the map drawn in ethnohistorical terms above, and very much at variance with that described in chapters 5–14 in terms of the practical languages of ethnic identity. In Liangshan today the following minzu are recognized: Han, Yi, Zang (Tibetan), Meng (Mongolian), Pumi, Naxi, Hui, Lisu, Miao, Dai, and Bai.

Han

Han are one of the least problematic minzu to classify, though there are problems in other parts of the Southwest with people who claim minority status but are officially classified as Han. Basically, Han are those who are left over when all claims of minority status are either recognized or rejected. They are mostly city-dwelling teachers and administrators or valley-dwelling peasants.

Yi

Yi is a very broad, inclusive category. In this area it includes people whose autonyms are Nuosu, Lipuo, Nasu, Shuitian (or Laluo), Tazhi, Yala, and Bai. Nuosu are the least problematical: they are uniform in language, self-identification, membership in one of a series of linked clans, and strict ethnic and caste endogamy. For most Nuosu people, Yi is simply the Chinese word for Nuosu. Lipuo living in Renhe and in areas of Yunnan immediately to the south also accept their identity as Yi, though they recognize cultural and linguistic differences from Nuosu and do not intermarry with them. Nasu, also called Abu in some of the literature, are descendants of the families of the tusi of Puwei and the marriage partners of his clan; some of them accept their identity as Yi and some do not. Tazhi, living in Puwei also, appear to have once been linguistically the same as the Nasu but members of lower-ranking clans who did not intermarry with the elite. Yala, also living in parts of Miyi, are of undetermined origin but do not currently accept their identity as Yi. Shuitian or Laluo, living in Renhe district and in parts of Huaping in Yunnan, did not accept their identity as Yi in the late 1980s when I visited them; they were eager to distinguish themselves from the Nuosu, whom they considered barbarians (Harrell 1990). By 1994 they still referred to themselves casually as Shuitian, but did not object to being called Yi. Finally, some people classified as Yi insist that they are Bai, a problem I take up in chapter 13. The lack of identity among these Yi groups can be explained, according to the official categories, by noting that Nuosu prior to 1956 were at the slave stage of society, while other Yi had already entered feudalism, so there were differences within the Yi minzu in terms of historical stages, which made closely related societies seem quite different from each other.

Zang (Tibetan)

People who would be thought of as Tibetans by Western scholars (speaking one or another of the languages of the Tibetan branch of Tibeto-Burman, and with cultural affinities to the speakers of one of these languages) do not live in Liangshan, unless one includes the far northwestern corner of Muli, which is really part of another culture area, or a few cadres and teachers. But other people, mostly Qiangic speakers formerly known as Xifan, or “Western Barbarians,” are classified as Zang. These include all Prmi speakers in Sichuan, many of whom were under the political jurisdiction of the monk-king of Muli, who was himself both an appointee of the Qing emperor and a vassal of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa. It was the wish of the last king of Muli that his realm be made a Tibetan autonomous region, and so the people living there and in adjacent areas of Sichuan were classified as Zang. Other Xifan groups in the corridor to the north are also classified as Zang.

Meng (Mongolian)

Descendants of the tusi—some of which were originally created by Qubilai, and some of which were established later, in areas that are now part of Sichuan—and of the retainers of these rulers, claim that their ancestors were members of Qubilai’s Mongol army, which conquered this area, even though most of the earliest records of the recently deposed dynasties reach back only to the Kangxi period (1661–1722) (Fu 1983: 138–46). They thus claimed Mongolian identity in the ethnic identification project, and this was ratified by the authorities in the 1980s (Li Shaoming 1986). In practice, this means that all Naze or Naru speakers in Sichuan are officially classified as Meng.

Pumi

Prmi speakers in Yunnan remained unclassified in the early stages of the ethnic identification project, but in 1959 some leaders of local Prmi communities conferred with authorities in Beijing and confirmed that they did not want to be classified as Zang, because they thought they, as Xifan, were different from Tibetans. They were thus made into a separate minzu called Pumi instead of the possibly insulting Xifan.

Naxi

In the 1950s Naze, or Naru-speaking, people in Yunnan, mostly around the Lugu Lake-Yongning region, were classified according to Stalin’s criteria as Naxi because of similarities in language and origin stories with the larger Naxi group centered around Lijiang (McKhann 1995). To this day most of the Naze-speakers in Yunnan wish to be known in Chinese not as Naxi but as Mosuo, because of their divergent political organization and marriage customs. So far, they have failed in their attempt to be known as Mosuozu, but they have extracted the concession that they can call themselves Mosuo ren, or Mosuo people (He 1991), while remaining part of the Naxizu. There are also a number of unproblematical Naxi scattered in small pockets in Ninglang, Yanyuan, and southwestern Muli.

Hui

There are several Hui villages in the Anning Valley—I have visited settlements in Xichang and Miyi—and there are small Hui communities in the county towns of Yanyuan, Ninglang, and Miyi. These people tend to practice at least some Islamic customs, and there are rather ornate mosques at Guabang in Miyi and at Yangjiaoba in Xichang, recently restored with state aid. In smaller townships, people of Hui ancestry tend to lose both their religion and their endogamy, and to become assimilated to Han identity; I do not know if these people actually change their minzu identification when this happens.

Lisu

No problem here. There are Lisu townships in very remote mountain areas in Yanbian, Miyi, and Dechang, and they remain separate and isolated from their Han and Yi neighbors.

Miao

There is a compact Miao township in Yanbian (Li Haiying et al. 1983), separated by altitude from its Han and Yi neighbors. There are also about five thousand Miao in Muli, many of them living interspersed and intermarrying with Han but not with Yi or Zang. These Miao belong to the southwestern branch of that ethnic category, call themselves Hmong in their own language, and are closely related to the Hmong who have migrated to America and Europe as refugees in the last twenty years.

Dai

Dai in this area are called Tai both in their own languages and in local Han dialects. They are descendants of detachments from Jingdong in Yunnan, sent by the first Ming emperor to help quell rebellions in the late fourteenth century (Sichuan Sheng Minzu Yanjiu Suo 1982: 94). They live in Renhe and Yanbian, commonly intermarry with neighboring groups, and are no longer Theravada Buddhists, if their ancestors ever were. Most of them still use Tai language at home.

Bai

Some people who are probably of Lipuo, Nasu, or other Yi ancestry have successfully, and some unsuccessfully, claimed identity as Bai. I discuss this further in chapter 13. There are also a few immigrants from the Dali region who are unambiguously Bai.

As can be seen already from these brief sketches, the minzu produced by the ethnic identification process are not the same as the ethnic groups defined in the practical languages of ethnic identity. These minzu categories, however, are far from irrelevant to people’s daily lives. Censuses and social surveys, for example, often include data classified by minzu affiliation. More important, being classified as a minority of any sort, as opposed to a Han, brings with it certain affirmative action benefits. In Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, rural minority couples are uniformly allowed three children, whereas rural Han can have only two. In Panzhihua Municipality, quotas vary from township to township, but townships with heavy minority representation tend to have higher birth-quotas. There are special schools and classes for minorities throughout the area, and members of minority groups usually receive preference when applying for admission to regular schools.

Membership in particular minzu is also important. In the areas designated autonomous prefectures or autonomous counties, or in the smaller minzu townships, members of the locally predominant minority minzu tend to be appointed to positions of political power and authority in the four wings of the state bureaucracy: the Party, the government, the legislature, and the People’s Consultative Conference. In addition, where there are programs of bilingual education, members of particular minzu are often offered the chance to become literate in their minzu language as well as in the national language, standard Chinese. For example, Prmi speakers in Muli, who are classified as Tibetans in a Tibetan autonomous county, learn standard written Tibetan starting in the third grade, using textbooks composed and printed in Lhasa. Prmi in Yunnan, classified as Pumi, are educated in Chinese only, since currently there is no written form of the Pumi language.

The Communist civilizing project has thus created a map of China, including the Liangshan area, that uses the metalanguage of ethnic identification and that channels administrative, educational, and developmental resources according to this map. In this sense, then, the map represents an important reality. It is not, however, quite the same as the reality of ethnic identity in the same region, which is the topic of the bulk of this book in chapters 5–14.

CONTEXTS OF INTERACTION BETWEEN DISCOURSES

These different languages of classification and representation are all relevant, in various ways and in various contexts, to the everyday lives of almost every person in Liangshan. For some, ethnicity is a fact of daily life, confronting them as soon as they step out the doorway in the morning, or maybe even before. People in places such as Baiwu Town or Shanhe Village in Gaizu live cheek-by-jowl with others who speak different languages, wear conspicuously different clothes, and occupy a different position in the local and regional political-ethnic order. For others, ethnicity is more remote but still relevant. Villagers in the mountains of Mishi see a non-Nuosu only when their child’s teacher visits their home, if she does, or perhaps when they travel, once or twice a year, to distant markets at Lianghekou or Xide City. Similarly, for Han workers or bureaucrats on the streets of Panzhihua or Xichang, minorities are nothing but folks in colorful costumes whom they see but do not talk to. Even for these people, however, their ethnicity is important: Han urbanites know that Liangshan is a Yi autonomous prefecture and that Nuosu thus have certain affirmative-action advantages, such as schooling at the minzu middle school and less restrictive birth quotas. Mishi villagers may not see Han people very often, but their conversation seems obsessed with what they see as the Han state’s encroachment in not completely comprehensible ways upon their land and lifestyle. Ethnicity thus flavors the life of everyone in Liangshan in a way that is simply not relevant for most people in China proper, where I have been told by several friends that they did not even know their own minzu (Han of course) until they were teenagers or young adults.

Ethnic difference and ethnic interaction are important for the people of Liangshan because they affect, and are expressed in, many concrete areas of people’s lives. These include language, culture and lifestyle, marriage and kinship organization, education, and local and regional politics.

Language

Probably a majority of the population of the core counties of Greater Liangshan is monolingual in Nuosu, with only a rudimentary knowledge, if any, of the Liangshan dialect of Southwestern Mandarin. There is very little occasion for anyone to use any language other than Nuosu, especially with the increasing availability of books, newspapers, and government notices written in that language. Most Han in the Anning Valley and in other areas of concentrated Han settlement are also strictly monolingual: I once astonished an old Han lady, a lifelong resident of Yanyuan, when she overheard me speaking Nuosu on the street, since she did not understand a word and considered the Nuosu language to be impossibly difficult, even though it was all around her. For most members of minority groups in the Lesser Liangshan area, however, bilingualism is a fact of life. One has to know Chinese to deal in the market, to get an education, even to talk to some of one’s neighbors. Of all the minority languages in the area, only Nuosu is readily available in written form (I have seen a few Lisu books, but never anything in Prmi or Naze, let alone any of the smaller Yi languages) or used formally in schools or for official documents, so literacy for many people means literacy in Chinese. At the same time, the daily environment for many people includes two or three vernaculars, so it is not uncommon to find people who speak three languages, especially if they are members of smaller groups who also have to deal with Nuosu as well as with Han or with the Hanophone state.

Small enclaves of speakers of languages other than Han or Nuosu have tended in recent years to lose fluency in their home languages. This gives rise to certain sad situations, such as visiting ethnologists yelling in the ears of poor deaf old ladies to elicit kinship terms or other ethnological gems, but most younger people I have talked to show little regret for the passing of their mother tongues. In some places, members of minority groups who do not speak each other’s language converse in Han, or occasionally even Nuosu. I rode in a jeep with a Prmi and a Naze woman from Gaizu to Zuosuo: they were dressed identically and lived in identical houses, different from those of local Han or Nuosu, but they spoke Chinese to each other, since they had no knowledge of each other’s language. Nuosu, by contrast, thrives even in small enclaves in the Anning Valley such as Manshuiwan (see chap. 8) and Yuehua.

In large cities, especially Xichang, by the second generation of residence most people of whatever ethnicity lose any language but Chinese.

Culture and Lifestyle

Certainly ethnic culture derives both from habit and from calculation: people retain the customs and costumes of their elders out of a feeling of comfort as well as out of a desire to communicate or display their identity in public contexts. There is no one-to-one correlation between customs and ethnic identity, especially over the broad geographic range of Liangshan. But in any particular local context, certain customs are singled out as markers differentiating between one ethnic group and another. In Liangshan, the most prominent cultural features used as ethnic markers are dress, food, housing, and ritual.

Ethnic dress is the most obvious indicator of group membership to an outside observer in Liangshan, and the most obvious item of ethnic dress is the skirt: all minority women have some sort of full skirt as part of their ethnic dress, while the only skirts worn by Han women are the straight, modern ones of younger women. Nuosu women in many areas, particularly in ethnically mixed areas of western Liangshan, wear the Nuosu skirt, blouse, and headdress all the time. In other areas, they may wear just the headdress, but there is no mistaking the ethnic statement made by full or partial wearing of ethnic dress. Members of other minority groups wear ethnic clothing more selectively; at present old women are more likely to wear skirts than are their daughters, but everyone wears them for special occasions. Nuosu men and women also wear the ethnically distinguishing jieshy vala, or felt cape and fringed cape, in cold weather.

Food and housing also bear ethnic messages. At least on feast occasions, Nuosu chunks of meat, along with Prmi and Naze fat pigback, attest to the ethnicity of the hosts, even in urban contexts. Houses tend to be built of materials that differ regionally, but the plans and furnishings are peculiar, in any one area, to a certain ethnic category.

Finally, religion and ritual are also salient ethnic markers. Members of all ethnic groups have some kind of ancestral altar in the main room of their houses, but it is in the corner for Nuosu, at the rear for Han, and in a variety of arrangements that differ regionally for Prmi and Naze. The nature of ancestral and spirit worship also differs, of course, from one group to another, as do wedding and funeral customs: Han bury their dead; Prmi cremate and leave prayer flags to mark the site of the ashes; Nuosu cremate and scatter the ashes on a mountain; eastern Naze cremate but hide the ashes in a mountain cache whose location is not revealed to any but their own clan. And there are minute differences even among the ways members of different ethnic groups celebrate the same holidays. Finally, some groups espouse Tibetan Buddhism, while others do not. All of these differences can be emphasized as aspects of ethnic interaction.

Marriage and Kinship Organization

In an area where members of diverse ethnic groups come into daily contact with each other, such as Liangshan, questions of ethnic endogamy and exogamy are bound to arise. Interviews in most villages elicit the idea that intermarriage is a modern thing, a consequence of social change and the Revolution. In some areas, this is no doubt true, but as with other aspects of ethnic interaction, each area displays its own particular pattern.

In general, Nuosu do not marry with other groups (even other groups classified as part of the Yi minzu) in the village context; they do not even intermarry among different castes of Nuosu. All other groups intermarry to a certain extent: Han will intermarry with anyone, anywhere, while other groups tend to be selective. In the cities and among educated people, all kinds of intermarriage are possible and frequent, with the possible exception of intercaste marriage among Nuosu. Any kind of intermarriage, of course, produces the problem of the minzu affiliation (and sometimes also the ethnic identity) of the offspring. In general, offspring of mixed marriages are classified as belonging to the non-Han minzu, because of the affirmative action benefits available. They may, however, acculturate to Han ways while retaining a minority identity; in chapter 13 I examine this situation in regard to the Lipuo case.

Marriage, however, is not simply a way of creating ties between groups; it is also used as a kind of ethnic marker to distinguish groups. For example, the ideal Nuosu marriage, reflected in the kinship terminology system (Harrell 1989, Lin 1961), is bilateral cross-cousin marriage, while other Yi-speaking groups such as Tazhi, along with Naxi (McKhann 1989) and patrilineal Naze, favor patrilateral cross-cousin marriage. This difference in systems not only serves as a marker, like any other custom, but renders marrying across the systems structurally problematical.

In addition to marriage, kinship organization also marks off one ethnic group from another in the local context. Naze and some Prmi in the Lugu Lake area are matrilineal and eschew marriage in favor of matrisegment households with visiting sexual partnerships. Han and Nuosu simply cannot participate in this kind of system; Naze who take up with Han marry them and live in patrilocal or neolocal families. It should be emphasized, however, that Naze in Guabie are patrilineal; since Guabie and Lugu Lake are several days’ walk away from each other, difference in kin systems does not preclude identification in some contexts as members of the same ethnic group (see chap. 11).

Education

Schools in China, as in any multiethnic polity, attempt to teach not only literacy and other important skills but also to inculcate patriotic sentiment, at least in their overt lessons and curricular materials (Keyes 1991, Harrell and Bamo 1998, Hansen 1999, Upton 1999). The ways in which they have approached this task have varied, however, with the general variance in ethnic policy, and in the Reform Era since 1979 the strategy has been to use ethnic particulars to inculcate national sentiments. Nuosu language texts, for example, show little girls in skirts and headdresses (never mind that little girls rarely wear them), and little boys in turbans with horns on the front (something I have never seen on little boys) studying lessons that include Chairman Mao, Tiananmen Square, and the brave soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Beyond the politics of using the particular to inculcate the general, however, there are a number of other ethnic aspects to education in Liangshan. Which language to use, and in what proportion, is a continual subject of controversy, not only in mixed areas (Should Prmi and Han students be forced to learn to read Nuosu?) but also in the ethnically homogeneous Nuosu regions of eastern Liangshan (Which language should be taught first, and which should be used to teach subjects such as history and mathematics?). Should there be classes in such languages as Prmi or Naze, which do not have widely used written forms? Is teaching Prmi students in Muli to read and write Tibetan, because they are Zang, a worthwhile investment of resources? Whom does it benefit?

Special schools and affirmative action are also a feature of ethnic education policy. Most counties in Liangshan, as well as Yanbian in Panzhihua, have specific ethnic middle schools, or minzu zhongxue, which are usually the second-ranked middle-schools in their counties, below the central county school but above the local schools in the larger townships. (The smaller townships have only elementary schools.) Within regular schools, there are often special classes composed only of minority students (minzu ban) or classes taught primarily in the Nuosu language (Yiwen ban). Minority students are given bonus points in entrance examinations for upper-middle and normal schools, and sometimes for technical colleges and universities, and they also have available an alternative track of higher education in the Southwest Nationalities Institute (Xinan Minzu Xueyuan) in Chengdu, or, for the best of them, the Central Nationalities University (Zhongyang Minzu Daxue) in Beijing.

Local and Regional Politics

As Thomas Heberer points out (2001), the term “autonomous” (zizhi) in the titles of such administrative units as Liangshan Yi Nationality Autonomous Prefecture does not really denote any kind of federal system where local areas have much fiscal or policy-making autonomy that is guaranteed as a constitutional right. The granting or rescinding of autonomous decision-making powers (and, for that matter, the granting or rescinding of constitutional rights, which has happened several times in the history of the PRC) is in the hands of the Party. In addition, many of the natural resources—particularly timber and minerals—found in the prefecture are under the control of units belonging to either the central or the provincial government. And there is no local control over population movement into or out of the prefecture, meaning that national- and provincial-level units have been able to bring in large numbers of primarily Han people in the last forty years, significantly altering the population until Liangshan Prefecture is now only 40 percent Nuosu and 57 percent Han (Liangshan 1985: 2).

At the same time, the term “autonomous” is not totally empty of meaning, either. Autonomous prefectures (such as Liangshan) and counties (such as Ninglang, immediately across the border) are able to retain more of their tax revenues (Guo 1996: 56–86) and can apply for subsidies for construction projects from the Nationalities Commission bureaucracies as well as the ordinary ministerial bureaucracies. They are thus currently more autonomous in fiscal affairs than are ordinary prefectures (diqu) and counties.

Another aspect of the “ethnic” character of these units is the preferential appointment of minority cadres to positions of power and responsibility. This policy, of course, was widely followed in the early 1950s, but in the radical Maoist times, especially with the formation of the revolutionary committees in the Cultural Revolution to replace Party and government leadership organs, Han officials were in control. Since the Revised National Autonomy Law of 1982, however, minority officials have again had preference in these positions (see chap. 3, n. 11).

Along with the appointment of minority cadres to high positions (and the incumbent patronage networks that tend, of course, to have an ethnic flavor) comes a great elaboration of the ethnic flavor of political events. At official banquets in Liangshan, young women (in fashionized versions of traditional Nuosu clothing) and young men (in entirely fantasized versions) sing, play the panpipes, and offer liquor to guests of whatever nationality, who are eating (even at a round table with chopsticks) at least one plate of pork or mutton chunks and one of buckwheat cakes or potatoes, along with their stir-fried dishes and white rice. Government offices, celebratory banners, and even the doors of government logging trucks sport Nuosu writing alongside Chinese (or, in the case of Muli, a Zang autonomous county, Tibetan alongside Chinese, even though about one quarter of the population of the county is Nuosu [Muli 1985: 2]).

The implementation of ethnic preference policies also varies greatly with the jurisdiction. In the upland areas of Yanbian and Miyi, both of which are counties within Panzhihua City that have no ethnic autonomous designation, the population is nevertheless almost entirely Nuosu, and this is reflected in the designation of most of the high-mountain areas as Yi townships (Yizu xiang). But Nuosu writing is nowhere in evidence except on a couple of government signs—all documents are entirely in the Han language, as is all schooling. Those who can write Nuosu (and there are not many) have learned on their own. Similarly, Nuosu are not prominent in the county-level administration of these counties, except on the Nationalities Commission. There is, however, an ethnic middle school in Yanbian, as well as a highly regarded minority class in the No. 9 Middle School of Panzhihua City, showing that ethnic preference policies are only weaker, not absent, in those areas that do not have the “autonomous” administrative designation.

This chapter has summarized generally how ethnic identity (as experienced in the everyday life of local communities) and official minzu designations (which govern much policy implementation in government, language, and education) interact to affect the consciousness, political strategy, and opportunities of individual members of those groups. In a short summary such as this, however, the different textures of ethnic group solidarity and difference, and cooperation and conflict are not really palpable. The ethnic solidarity and ethnic relations of different groups are informed and upheld by different notions of ethnic identity. The following chapters explore these different modes of being ethnic for a series of different groups in Liangshan today. Within each group we explore a number of different local contexts to demonstrate more realistically the ways in which ethnic identity and nationalities policy intertwine in the lives of Liangshan’s people.

1. I am using “tribal” here in the narrow sense suggested by Fried (1967: 170–74)—that is, a secondary, semicentralized polity that arises on the periphery of, and in response to pressure from, a state system. See chapter 2.

2. Figures were collected from county and prefectural offices.