On the Dynamics of Tai/Dai-Lue Ethnicity

An Ethnohistorical Analysis

The Tai-Lue, a Tai-speaking people who now live mostly in Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan,1 are unlike other non-Han ethnic groups in this frontier province, most of whom are divided into distinct, noncentralized units. Although the Tai-Lue have had the full experience of running a state, in their case a kingdom, at present they are counted as a subgroup of the Daizu (Dai nationality)—recent contact between the Dai-Lue and the Han has transformed the Dai-Lue from an independent kingdom to a subgroup of a minority minzu. To understand the relationships between the Dai-Lue and Chinese state, we must adopt an ethnohistorical approach, exploring changes in the ethnic status of the Dai-Lue.

The Dai-Lue are an example of how a minority ethnic group, whose former state is not recognized by the dominant group, copes with an actual nation-state that does not recognize itself as such, but claims instead to be multi-ethnic. The Dai-Lue story can be used to explore the universal effectiveness of the framework of official “nation-state” (cf. Anderson 1983) versus “minority ethnic group” in shaping ethnicity in Socialist China, and to demonstrate that the model of one “ethnic-state” (a premodern state established by a single ethnic group) among others can be a fruitful approach for understanding processual ethnic relationships.

SIPSONG PANNA AS A TAI KINGDOM

To determine whether Sipsong Panna was once a kingdom is not so silly a task as determining whether China was an empire before it was a republic. After all, “Chinese empire” is a bit of historical common knowledge, while “kingdom of Sipsong Panna” awaits our investigation and verification. The “state of Sinsong Panna” may vanish permanently under the conservative interests of certain Western Southeast Asianists and the never-ending distortions of Chinese Xishuangbanna studies. If such is the case, it not only will be unfair to the people of Sipsong Panna, but also probably will distort future studies of Sipsong Panna society and culture.

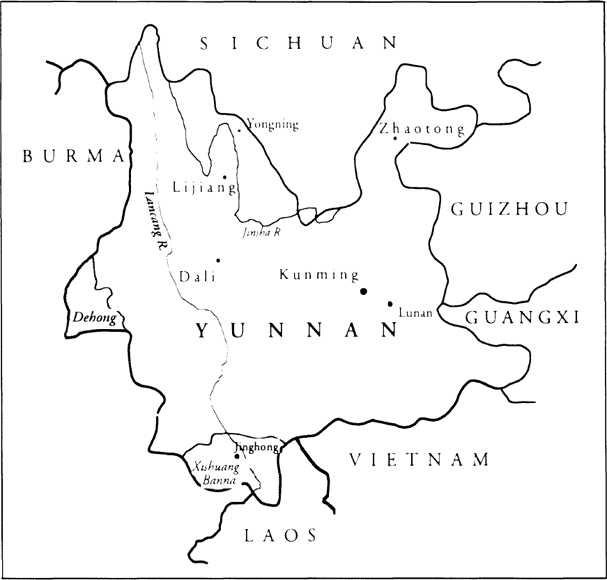

MAP 6. Yunnan and neighboring areas

Because the kingdom of Sipsong Panna never received recognition from the world’s “legitimate” powers, it completely disappeared from the network of international affairs, except when Siam2 attempted to unify all Tai peoples (including the Tai-Lue in Sipsong Panna) during the 1930s and 1940s. No one knew where Sipsong Panna went, how it had been treated, or whether it survived.3

The Role of the Chao Phaendin: Ethnic Identity as Subjecthood

The symbolic significance of the chao phaendin (king) is crucial to understanding ethnic solidarity among the Sipsong Panna Tai. Like the Japanese imperial family, the royal house of the kingdom of Sipsong Panna was one unbroken family line since 1180. The Sipsong Panna kingship maintained an effective centralized government through a native network of dominance that had nothing to do with the imaginative authority of the Chinese-appointed Cheli junmin xuanwei shi (lord of the Cheli [i.e., Sipsong Panna] pacified administrative region for governing people).4

The ideology and behavior patterns of people under a king and those under a chief or tribal head are fundamentally different. People ruled by a king are passive with respect to the state. The king’s people know they are living in a secure or fixed area because of the king. The king both ensures the survival of his populace and is the emblem by which the people identify who they are and what they belong to.

This explains the existence of strong nostalgia among the Lue of northern Thailand (cf. Moerman 1967, 1968): the people miss their home country with its royal chao phaendin. It is not surprising that in 1986 tens of thousands of Lue people came to kowtow to Chao Hmoam Gham Le (Dao Shixun), the last king of Sipsong Panna, when he visited the Lue community in Nan, northern Thailand, after presenting a paper as an ethnolinguist at an international conference in Chiang Mai.

Sipsong Panna was not a protectorate of China and Burma; it had absolute rights in military action, foreign affairs, economic activities, and internal governance, and neither China nor Burma ever signed a treaty for its protection. Sipsong Panna recognized that the great powers standing by it possessed a sort of superiority, but she was out of the range of the Middle Kingdom (Zhongguo, i.e., cultural and ethnic China).

Both Le Bar (1964) and Moerman (1965:1219; 1967; 1968:154) found that various northern Thai groups, whose dialects were mutually intelligible, nevertheless maintained airtight ethnic boundaries. They hypothesize that the remembrance of disappeared states to which those peoples belonged—such as Lan Na (northern Thailand) for the Tai-Yuan, Lan Zhang (Laos) for the Tai-Lao, and Sipsong Panna for the Tai-Lue—still perform a critical function of distinguishing selfness and otherness in daily ethnic interactions. Both Le Bar and Moerman are basically right, but there is more to the question than this. In Sipsong Panna, members of a particular lineage could live in several villages. Each person was expected to fulfill obligations to his lineage and village, receiving benefits and enjoying rights from both sides as a result. The name of the head of a lineage was used as the name of the lineage. When the head of a lineage died and a new leader was selected, the lineage name changed. There were no surnames in Tai-Lue. In other words, a Tai-Lue lineage did not form a cultural unit or have a cultural identity, because the lineage is not the same as the village, the village being a political unit. Membership in a lineage does not confer benefits, but membership in a village does. The general principle of egalitarianism among commoners in Sipsong Panna assures that in regard to obligation to the chao (“king,” “noble,” or “master”), every village is equal and every non-chao person is equal. Because each household raises the same amount of money or crops for the chao, rather than sharing payment from every lineage, the lineage never developed into the clan, nor was primordial ethnic identification sought from the lineage or descent line.

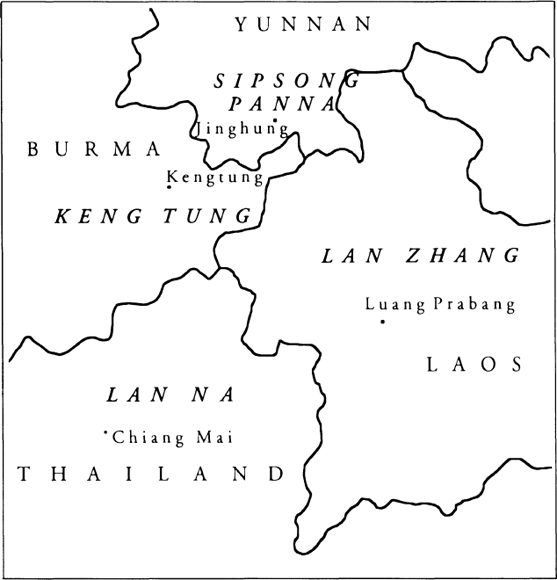

MAP 7. Historical Tai kingdoms and modern states

Despite the political importance of the village, however, a person rarely belonged specifically and permanently to a particular village, but could move back and forth freely. A village thus was a location for lodging and doing one’s obligation only, and was not important in forming group indentity because no matter where one stayed, one was always a xa (slave) of the chao. Chao, in this sense, refers only to the chao phaendin, because people could also migrate among different meeng (local principalities). A particular chao meeng (prince) might not mean anything in the process of ethnic identification to most of the people in Sipsong Panna. The only predominant symbol of unity in the Lue area was the chao phaendin. He was the greatest chao wherever a person traveled (as long as that person was a Lue), in his effect on ethnic psychological boundaries (De Vos 1982:6). Such boundaries, according to De Vos, “are maintained by ascription from within as well as from external sources which designate membership according to evaluative characteristics which differ in content depending on the history of contact of the groups involved” (ibid.:6). In other words, in the case of the Tai-Lue, the more the people interact with the other Tai-speaking groups (e.g., in Lan Na, Lan Zhang, and Keng Tung [northeastern Burma]), the more the chao phaendin is strengthened as a symbol of Lue group unity.

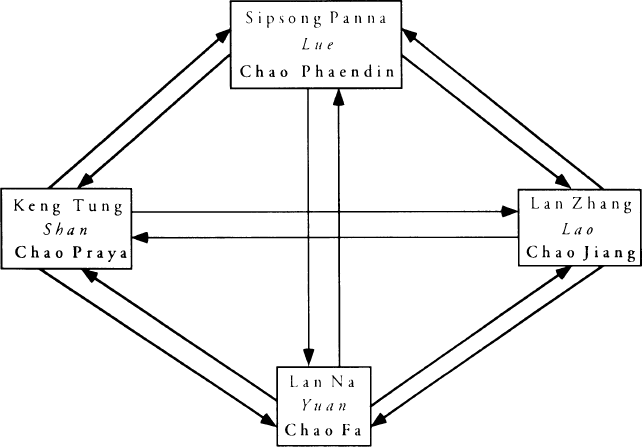

The chao phaendin is unique to the Dai-Lue, differing from the chao jiang of Lan Zhang, the chao praya of Keng Tung, and the chao yuan of Lan Na. These four small Tai kingdoms frequently interacted with one another, both in interstate affairs and in popular contact, before modern nation-states were formed. People speaking mutually intelligible dialects felt free to move to and fro. This was an adaptation to encirclement by powerful neighbors: Burma, Siam, Mons, Cambodia, and China. When one of the four northern Tai states was attacked, people could move quickly and safely to other territories to reside temporarily.5 This “tacit alliance” functioned as political unification, although a formal agreement was not conducted. However, each state’s members maintained the identity of their origin, because they had their own supreme chao.

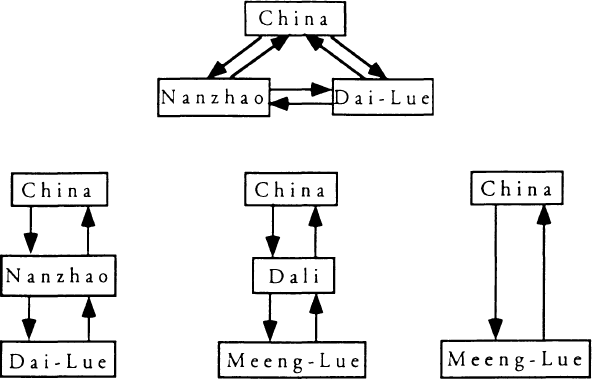

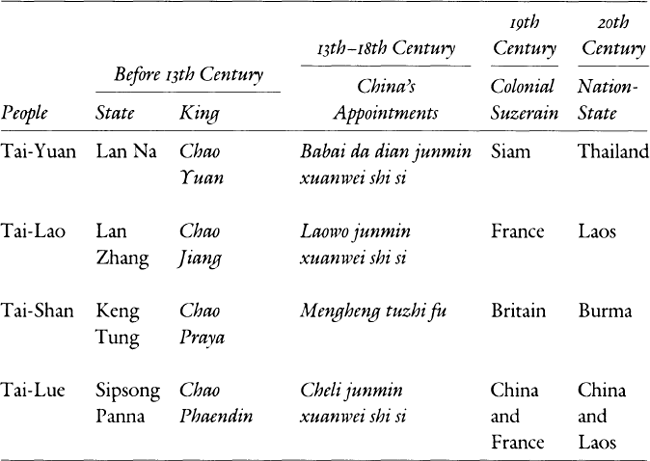

It is clear that members of this ethnic group had their original identity, no matter where they were living. This basically answers Moerman’s questions about the nostalgia of the Lue toward Sipsong Panna and about the dynamic relations between various northern Tai ethnic identities and historical states (fig. 1). These four states also established their own regimes based on one or several particular principalities and separately received four different official titles from China. Today they belong to four independent nation-states. These four units were never combined in any way by any power. Table 1 illustrates these relationships. The political situation thus strengthened the formation and maintenance of ethnic boundaries among these northern Tai groups.

FIGURE 1. An interactive network of the four Tai kingdoms in northern Southeast Asia, showing geographic areas, ethnic groups, and titles of rulers

The chao in the Lue area became a major symbol of identification, which was reflected in the equal distribution of the common people’s obligation to him. Although the people were classified into two categories, tai meeng and kun hen tsau, it was expected that they do the duties expected of their class. Tai meeng (“Dai of the meeng”—similar to the khon myang of Chiang Mai [cf. Hanks 1983]) were responsible for the public affairs of the state as well as for the external business of the king. Kun hen tsau (people of the chao) were responsible for managing the internal affairs of the king. In sum, tai meeng devoted themselves to making the chao’s state strong, and the kun hen tsau provided a comfortable life for the chao. We can thus boldly interpret the term Dai-Lue as meaning “the people who call themselves Dai, live in Lue, and share equally in making their chao phaendin a satisfied king.”

TABLE 1

The Changing Political Positions of the Four Northern Tai Kingdoms

The Tai-Lue View of China

Even before the Tai-Lue, led by Chao Bhaya Cheeng (r. 1180–1192 C.E., first king of the Tai-Lue) established the state of Golden Palace of Jing Rung in Sipsong Panna at the end of twelfth century (cf. Wang Jun 1982), the rulers of Lue knew well that there was a powerful state to the north. The name of this state was the Heavenly Dynasty and its leader was the chao wong, chao lom fa, or chao fa wong (great emperor of heaven). Although over time the state of Tai-Lue developed an effective strategy to cope with this powerful entity, which hypothetically might destroy it at any time, the Tai rulers were not aware of the political situation in China at all. The principle was that whenever anyone came from the north in a certain capacity, accompanied by a powerful army, and claimed his status as a representative of the Heavenly Dynasty, the Tai rulers immediately showed their loyalty and steadfast good faith to the chao wong. When the envoys or generals of Nanzhao (Dali or Houli) came to Sipsong Panna, Nanzhao was treated as the Heavenly Dynasty. It is thus not surprising that Tai records concerning Houli mention that the chao lom fa was named bodhignian (king of Houli) and that he conferred a golden seal in the shape of a tiger head upon Chao Bhaya Cheeng. Nor is it surprising to read that Ghae Neeng (1192–1211), the second king, pledged allegiance to the chao fa wong of the Haw (Hok) dynasty (Li Foyi 1947:1–4).6 Many Chinese ethnologists and historians still insist that the chao fa wong whom Bhaya Cheeng and Ghae Neeng contacted was one of the emperors of the Song dynasty of China, even though details of the relationships between Yunnan’s kingdoms and the Lue state established by Bhaya Cheeng are unknown. Even for the Yuan empire, which presumably controlled the whole of Yunnan including the Tai-Lue, details of the interactive process between China and the Lue state are obscure. The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries seem to have been a period of adaptation by the Dai in order to get along with China, formation of a centralized Lue kingdom out of the domain of Bhaya Cheeng’s descendants, and establishment of formal relations between the Dai kingdom and China.

At this time, the rulers of the Lue state, or other indigenous chiefs in Yunnan, might have made some observations concerning the great Heavenly Dynasty’s response to unrest in vassal states: (1) To pacify a fight, attack, or rebellion occurring in an indigenous area, the Heavenly Dynasty always simply handed down imperial instructions to conciliate. If an indigenous leader raised armies for purposes such as expanding territories, or avenging a blood feud, he stood only about a 50 percent or smaller chance of causing China to send a punitive expedition. (2) If the Chinese army did come, a rebellion might be unsuccessful, but because of fighting in unfamiliar geographical circumstances, or because of sweeping malaria epidemics, many Chinese soldiers might be killed. Experience had shown that troops always withdrew very quickly, mainly because of malaria, so indigenous states or tribes were not too anxious about being destroyed. (3) Still, the political and military strength of China impressed the non-Han aborigines. The best strategy was to declare oneself a vassal first, then do as one pleased. (4) If that behavior went against the Heavenly Dynasty’s wishes, envoys should be sent with gifts to appease the emperor. Indigenous leaders who behaved thus not only rarely received punishment from China, but usually received more valuable return gifts from the Chinese emperor through the returning envoys.

If we review the materials of the Ming and Qing periods carefully, we will find that the Lue state followed these guidelines in dealing with China ever since the eighth king, Chao Gham Meeng, began formal contact with the Heavenly Dynasty in 1382 and accepted the title of Cheli junmin xuanwei shi. However, after the kingdom of Kausambi (Chinese-Shan)7 in western Yunnan was destroyed in 1448 by the Ming army after a sixty-three-year-long rebellion against China (cf. Yang Yongsheng 1986:44–47; Huang Huikun et al. 1985:82–86), the Tai-Lue rulers understood that the only way to survive was to serve as a xuanwei shi.8

THE CHINESE INTERPRETATION OF THE STATE OF LUE

The statement that “China has been a united state composed of multiple nationalities” is both a popular, dogmatic statement of political propaganda (e.g., Art. 4 of the 1978 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China) and a universal Chinese academic conclusion (e.g., Ma Yin 1981:1–25; Zhang Quanchang 1984:330). Socialist ethnologists, following the Communist Party’s philosophy and policy, have expended a great deal of energy explaining the relationship between the key concepts “united state” and “multiple nationalities.” Tibet is a good example of Chinese scholars’ attempts to verify that contemporary non-Han ethnic groups have always lived in territories of the Chinese state (Liu Shengqi 1988:11–15). The anti-Han movement there in the 1980s and 90s is accused of betraying the “Chinese minzu” (Zhonghua minzu). All non-Han states of the past have been classified as “local regimes” (difang zhengquan). The central regime is always China, although it may reasonably include several local units.

The term “regime” (zhengquan) does not refer only to a form of government, such as a socialist or autocratic regime. In socialist China, all levels of administrative units—such as villages, townships, autonomous counties, autonomous prefectures, and provincial governments—are separately called regimes. All regimes other than the central one are referred to as local regimes. This arrangement and interpretation serves to make the traditional relationships between non-Han and Han more rational, acceptable, and congruent with the contemporary situation. By this logic, non-Han states of the past, such as Tufan (Tibet) and Nanzhao, have not changed, but are now considered to be completely under the control and domination of the central government.

It is not hard to imagine the political status that Sipsong Panna, a much smaller state than either Tibet or Nanzhao, is accorded in this analysis. According to The History of the State of the Lue, “Chao Bhaya Cheeng came to be the leader of Meeng Lue in the Cula Calendar [Chulasakkharaja, a kind of Buddhist calendar used by the Sipsong Panna Tai and the other Buddhist societies of Southeast Asia] year 542 [1181 C.E.]. . . . Chao Lom Fa Bodhi Gnian granted him a golden tiger-head-shaped seal, and appointed him master of this area. . . . He was called Shomrdieb Bra Pien Chao [Greatest Buddha] or Meeng Jing-Rung Meeng Huo-Gham [the Golden Palatial State of Jing Rung]. Bhaya Cheeng went on to rule Lan Na, Meeng Gao [Vietnam], and Meeng Lao [Laos]. At that time, the emperor of the Court of Heaven was the world leader” (see Li Foyi 1947:39). Based on this account of Tai history, we now have alternative interpretations by four Chinese scholars:

1. Li Foyi: “The term zhao long fa [chao lom fa] was usually used to address emperors of China. However, here it should refer to Duan Zhixing, king of the state of Houli [one of the regimes of Nanzhao]” (1984:4).

2. Zheng Peng and Ai Feng: “In the Tang and Song periods the area of Xishuangbanna was within the jurisdiction of Nanzhao and Dali, two local regimes of the Tang and Song” (1986:16)

3. Huang Huikun, vice-president of the Yunnan Institute of Nationalities and an influential ethnologist in China, and his coauthors: “ ‘Court of Heaven’ here should refer to the Song dynasty. Bhaya Cheeng became the master of this particular area because he received the golden tiger-head-shaped seal from the Court of Heaven. . . .” (1985:56)

4. Jiang Yingliang, a professor at Yunnan University and a famous Dai specialist: “We must keep in mind that since ancient times Xishuangbanna has been a part of the territory of our mother country. The state of Jing Rung established by Bhaya Cheeng was a local regime under the domination of the Song dynasty of China. The master of Jing Rung accepted a rank of nobility from the Song government” (1983:182). Jiang also explains that the term chao lom fa might be related to the lord of the state of Dali. Lom in Dai means “below” or “down.” Fa means “heaven,” which comes from the term chao fa wang (king of heaven), used to address the emperor of China. Chao lom fa should thus be translated “the king who is smaller than the king of heaven.” Chao lom fa, according to Jiang, refers to either the lord of Dali or an emissary from chao fa wang, the emperor of China (ibid.).

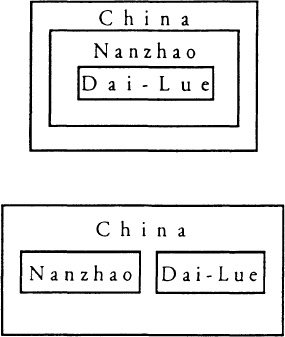

Except for Li Foyi, all the authors cited here are socialist scholars. Their interpretations clearly reflect the contemporary dogmatic theory of relationships between non-Han and Han peoples. These scholars and others who are familiar with historical accounts of the Tai-Lue and the state of Jing Rung know that no information on the Tai can be found in Song historical records. They also know that the evidence suggests that Nanzhao, Dali, and Houli were independent kingdoms.9 Yet they still neglect or distort the evidence. According to many Chinese Communists, including academic scholars, all research should serve the unification of the socialist motherland. In their view, the relationships among China, Nanzhao, and the Dai-Lue take one of the forms illustrated in figure 2. They do not recognize any of the networks illustrated in figure 3.

FIGURE 2. The Chinese official view of the relationships among China, Nanzhao, and the Dai-Lue

Since the fifteenth century, when the Ming dynasty swept the whole of China, Sipsong Panna10 and the Chinese government have interacted much more. However, the new relationships were just like those between China and Burma, Laos, and other areas.11 Cheli or Sipsong Panna was one of the appointed Xuanwei shisi whose sole responsibility was to submit tribute to China’s emperor and to not commit aggression against China’s borderlands. Statistics indicate that in the 543 years of the Ming and Qing dynasties, Sipsong Panna sent troops to occupy a region of Yunnan only once,12 sent tribute at least eleven times, received gifts and rewards from Chinese emperors more than seven times, and was never invaded by China. All this gives the impression of a long-lasting, stable, and peaceful relationship between Sipsong Panna and China.

FIGURE 3. Alternative historical interactive relationships among China, Nanzhao, and the Dai-Lue

Only after China’s Cheli junmin xuanwei shisi had been established for 650 years (from 1293 until the “liberation” of Xishuangbanna in the 1950s) did the Chinese government learn about the political and social features of the Dai-Lue state. China finally understood that Cheli xuanwei shisi was also known as Sipsong Panna, that Cheli was Jing Hung to the Tai, and that the Cheli xuanwei shi appointed by the Chinese government was chao phaendin (the lord of the broad territory—i.e., the king) to the people of Sipsong Panna. The Chinese also realized that the twelve panna or thirty-odd meeng were local executive units managed by the chao panna (lord of panna) or chao meeng (lord of meeng) of the centralized hierarchical government in Jing Hung, the capital of Sipsong Panna. The position of Cheli xuanwei shi, in sum, was not, as the Chinese had thought, simply an appointed indigenous office under the tusi system of Chinese political organization.

Although Chinese interpreters have never considered Sipsong Panna to be an independent state, we know that the remembrance and imagination of the previous Lue state in northern Thailand is an important element affecting both the Tai-Lue’s daily life and the process of their ethnicity (Moerman 1967, 1968). But what kind of state was it? Why do the Lue miss their home country so much? And how was image of that state formed in the Lue mind’s eye? The Lue living elsewhere talk freely about their state, whereas those in Xishuangbanna are not allowed to think of it as a formerly independent state. Is there another significant or dominant symbol that can replace identification with a past state as a marker of group identity among Xishuangbanna Dai under Communist rule?

THE XISHUANGBANNA DAI UNDER CHINA’S ETHNIC POLICY

According to empirical observation, and learning from the experiences of the Soviet Union on ethnic problems, since very early in the history of the Chinese Communist Party, differential treatment of Han and non-Han peoples has been part of the general ideology.13 Although a number of strategic resolutions, announcements, and promises made by the Party regarding minorities—such as “freedom to be independent,” “freedom to break away from China’s rule,” or “freedom to build their own state”—were deliberately omitted after 1949 from all kinds of published materials, including official documents, a separate policy agenda for minorities was maintained at all times. It was referred to as “regional national autonomy” (minzu quyu zizhi). The Sipsong Panna area is one such autonomous unit, referred to as Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture. This prefecture, which includes neither the Dai nationality outside Xishuangbanna nor any historically non–Sipsong Panna district in the territory, was founded on January 24, 1953. It includes three counties: Jinghong, Menghai, and Mengla. The capital is Yunjing-hong, in Jinghong County.

The Dai-Lue have been living in the Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture with the same Dai prefect, Zhao Cunxin, for nearly thirty-five years. During this period slogans, official documents, personal speeches, and journalists’ reports—similar to those about other minorities elsewhere—have given wide publicity to the huge success of Dai national autonomy. People have become used to praising the liberation by the Communists. A poem “composed” by dang jia zuo zhu de (master) Dai singers is representative of this:

Since the Communists came,

Fortune has landed on the frontier.

The great kindness of the Communists is endless.

When the autonomous region was founded,

Fresh flowers blossomed,

The fragrance of the flowers spreads hundreds and thousands

of miles,

The nationality policy warms our hearts.

(Zheng and Ai 1986:74)

However, the uncertainty of the political status and social structure of Xishuangbanna under Chinese rule is reflected in the fact that it was not until 1984 that the Law of the People’s Republic of China for Regional National Autonomy (the first formal law on ethnic autonomy) was promulgated, followed in 1987 by the Law of the Yunnan Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture for Self-Government.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THE DAI-LUE AND OTHER TAI-SPEAKING GROUPS

“Ethnic identification” is another process through which the Chinese government deals with the world of non-Han peoples. However, this process cannot be regarded simply as ethnic identification as the term is commonly used in anthropology. Fei Xiaotong, a leading sociologist and anthropologist in China, states that “ethnic identification is a scientific task for the purpose of serving ‘work among ethnic minorities’ [minzugongzuo]” (1981a:30). It is therefore a political strategy serving the aim of stable domination (for more discussion of its process see the Introduction to this volume).

During the process of ethnic identification, several groups were said to “not require ethnic identification because they have been universally acknowledged” (Lin 1987:1; Fei 1981a:6). The Dai, along with Mongolians, Manchurians, and Tibetans, were convinced that they were such a group. The problem was that, although the “obvious” status of the Dai came about because they were easily observed and frequently interacted with the Han, all identification work was conducted from the Han point of view. The various groups of Dai thus were asked to accept all the officially identified Dai outside their own homelands as “brothers” even though the majority of Dai groups had rarely or never contacted each other before.

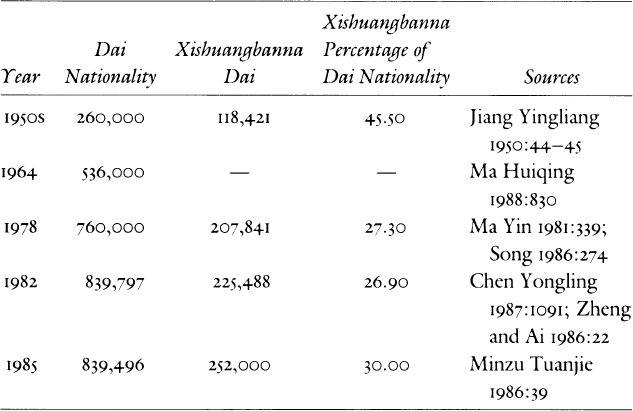

Dai population since the 1950s and the percentage who are Xishuangbanna Dai are illustrated in table 2. Despite the absence of figures concerning the Xishuangbanna Dai for 1964, we can conclude that they have made up approximately one-third of the Dai population of China since the end of 1970s. The non-Xishuangbanna Dai—the majority—must be seriously considered if we are to understand the official Communist and Han concept of “the Dai.”

The Dai are for the most part found in Yunnan. Besides Xishuangbanna, the major Dai areas include Dehong Dai and Jingpo Nationality Autonomous Prefecture, Gengma Dai and Wa Nationality Autonomous County, and Menglian Dai, Lahu, and Wa Nationality Autonomous County. There are also Dai communities scattered in Jingdong, Jinggu, Puer, Lancang, Xinping, Yuanjiang, and Jingping (Ma Yin 1981:339), and in a few counties in southern Sichuan.

The Dai were classified as a minzu that did not need to be reidentified. This is not only because all Dai groups—such as the Dai-Lue, Dai-Duan, Dai-Beng, and Dai-Ya—call themselves Dai, but also because they have been called by the same name (Baiyi) by the Han since the thirteenth century (cf. Jiang Yingliang 1983:109–121).

When the Han began contact with the Tai, the feature of Dai society most apparent to Han eyes was the bai (also known as bui). The most important social activity for both communities and individuals among the Tai, the bai is similar to the potlatch, its central purpose being economic redistribution. “Doing bai is a major focus of Tai cultural life; people sacrifice greatly for it, working hard and saving money just to be able to do bai” (Li Jinghan 1942:52).

TABLE 2

Relative Populations of the Dai Nationality and the Xishuangbanna Dai

NOTE: The number of Xishuangbanna Dai was provided by the vice-prefect of Xishuangbanna Autonomous Prefecture

It is my opinion that because the sound bai cannot be represented by a single Chinese character, the Han combined the characters bai and yi to form Baiyi. Almost all Chinese ethnologists and Dai specialists, however, such as Huang Huikun and Dao Shixun (Chao Hmoam Gham Le, in conversation) and Jiang Yingliang (1983), contend that Baiyi came from the Chinese term bai (white) yi (clothing). However, the character used to write the homophone yi  in Baiyi means “barbarian.” The Communist government, in keeping with its policy of “ethnic equality,” severely criticized former reactionary feudalistic regimes’ use of the insulting name Baiyi. But it is true that the Han have used the name contemptuously.

in Baiyi means “barbarian.” The Communist government, in keeping with its policy of “ethnic equality,” severely criticized former reactionary feudalistic regimes’ use of the insulting name Baiyi. But it is true that the Han have used the name contemptuously.

When the Han moved to Yunnan in greater numbers they recorded the general activities and some features of the Baiyi, and by the fourteenth century they had a fairly complete view of where the Baiyi were distributed. The Han adopted terms such as Han Baiyi (Dry Baiyi), Shui Baiyi (Water Baiyi), and Huayao Baiyi (Colorful-Belt Baiyi) to distinguish between various “styles” of Baiyi. Ironically, quite late—in the 1940s and 1950s, when the Dai nationality was formed—members of one group of Dai typically knew little or nothing about other Dai groups, though most individual Dai knew of their identification as Baiyi. As a result, the Chinese Communist Party introduced Dai groups to one another during the process of defining ethnic distinctions.

DAI-LUE ETHNICITY TODAY

As mentioned above, most groups who call themselves Dai and were earlier called Baiyi did not have recorded historical contact with one another. The two major Dai groups today, the Xishuangbanna and the Dehong Dai, use completely different written languages, and speak mutually unintelligible Tai languages. Their styles of dress, patterns of settlement, and original political systems are disparate. The kingdom of Sipsong Panna and the principalities of Dehong had almost no contact with each other. Chao Hmoam Gham Le told me, “I didn’t know that there were Tai people living in the Dehong area until I passed through there in June 1947.” When the Chinese communist process of nationality creation was in full force, it was the first time those two major Dai groups were face-to-face, recognizing a possible relationship as “siblings.”

In 1951 the representatives of various Dai groups met in Beijing to discuss the Chinese name of their people. The representatives of Dehong suggested using Tai  (as their name for themselves still is pronounced), but the Xishuangbanna members wanted to adopt a word with the sound dai. Finally, to settle the quarrel, Prime Minister Zhou Enlai synthesized the character

(as their name for themselves still is pronounced), but the Xishuangbanna members wanted to adopt a word with the sound dai. Finally, to settle the quarrel, Prime Minister Zhou Enlai synthesized the character  and the radical

and the radical  (which means “people”) to create Dai

(which means “people”) to create Dai  . Thus the word Baiyi was replaced by Dai, and Dai people began learning the Chinese character and calling themselves Daizu (Dai nationality). Because there is just one Dai nationality in China, the Xishuangbanna Dai, for example, must realize that they have many new brothers and sisters whose numbers are about three times the population in Xishuangbanna.

. Thus the word Baiyi was replaced by Dai, and Dai people began learning the Chinese character and calling themselves Daizu (Dai nationality). Because there is just one Dai nationality in China, the Xishuangbanna Dai, for example, must realize that they have many new brothers and sisters whose numbers are about three times the population in Xishuangbanna.

Nevertheless, it appears that relationships among various Dai groups did not change at all. Rather than sending invitations to one another for New Year’s Day, Dai groups still have nothing to do with one another. This is not only because of traditional lack of contact or rivalries, but also because the Chinese government pursues regional national autonomy instead of a single nationality autonomy. Xishuangbanna and Dehong have never had a chance to combine into an autonomous political unit, because they belong to different regions. This policy presumably can prevent the Dai from unifying to form a threatening nationalism. For Xishuangbanna Dai, there are no benefits in pursuing common identity with other branches of this artificially constructed Dai minzu. Each knows the others are members of the Dai nationality, and that is about all.

In sum, the Dehong Dai do not mean anything, in a cultural or social sense, to the Xishuangbanna Dai. If we take Keyes’s definition of ethnic groups (1981:3–30), these two groups of Dai lack both the sense of sharing the same origin, and a common motivation to pursue social interest, and thus should not be classified as belonging to the same ethnic group. The instrumental approach (Barth 1969; Duran 1974:43; Nagata 1974; Hinton 1983; Lal 1983; Burgess 1978), which says that a particular group of people claims ethnic status in pursuit of immediate interests, seems to be better able to explain the Daizu as an ethnic group. The officially created Dai nationality is a meaningful term for individuals only when it has a practical application. Although Dai status is based on recognition by the government, Dai often skillfully manipulate the ethnic component involved in a situation, revealing their identity in order to receive particular benefits (such as extra points on school entrance examinations), or concealing it if it does not have practical function (in daily life). Although when the Daizu was created and defined the name may not have meant anything to most Dai people, it is possible that the Dai may begin to function as an ethnic group in the future if situations offering advantages from such status occur. For the present, Daizu is more like an ethnic category, as defined by James McKay and Frank Lewins (1978) and Peter Kunstadter (1979:119–63), in that either “there is no sense of belonging” (McKay and Lewins 1978:418) or there exists nothing that creates similar consciousness and mutual interests (Kunstadter 1979:119).

Tai/Dai or Lue ethnicity has been persistently shaped by the processes of ethnic-political interaction between the Lue and China/the Han, the Lue and non-Tai hill tribal peoples, and the Lue and the other Tai-speaking groups. The Dai have identified themselves as such for at least several hundred years. However, they have adjusted their ethnic positions in a historical process that depends on changing political environments. As present, the Han, the hill tribes, and the other Tai-speaking peoples still comprise an ethnic network with the Xishuangbanna Dai, affecting their attitudes and interpretation of their ethnic position.

In the Chinese mind, the Xishuangbanna Dai are not an independent group of people, but rather the members of the Daizu who live in Xishuangbanna.14 Since the concept of Daizu is absolutely concrete, Chinese scholars who study the Dai usually proceed from the conception of Dai nationality. For example, when they compare the Dai in Dehong and the Dai in Xishuangbanna without considering the essential interactive relationship between the two groups, they conclude that the Dehong Daizu are more sinicized than the Xishuangbanna Daizu, because the former contacted the Han much earlier (see Huang Huikun et al. 1985; Jiang Yingliang 1983). Thus one chapter in any book dealing with Dai history or culture inevitably deals with the Dehong Daizu, and another with the Xishuangbanna Dai, even though the contents of the two chapters are mutually irrelevant.

The Chinese government’s policy of regional national autonomy revolves not around individual minzu, but rather around locality. This policy prevents Dai subgroups from forming one ethnic group, because they have no common interest. At the same time, this policy keeps the Xishuangbanna Dai an ethnic group as before. In the past, Sipsong Panna interacted with China as one state to another (Sipsong Panna to China) or one ethnic group to another (Tai to Han). Although Sipsong Panna’s state status has disappeared, China, represented by the Han people, still faces a single ethnic group in Xishuangbanna—the Dai-Lue—instead of dealing with the entire Daizu at once. The Xishuangbanna Dai have always acted as a unique ethnic group in their relationship to China/Han people, but outwardly, the Xishuangbanna Dai are now only part of a minority minzu, even though essentially they are an independent minority people to the Chinese administration that has relations with Xishuangbanna. In order words, the Daizu as a whole are still an “initial minzu” that does not function as an ethnic group.

Although from the perspective of the Han in Beijing or even in Kunming the Xishuangbanna Dai may appear to be a very weak minority people because they are just a subgroup of one of the fifty-five minority minzu, in Xishuangbanna they still hold the majority position.

The term Xishuangbanna is a Chinese transliteration of the Dai term Sipsong Panna. This prefecture is an autonomous political unit whose prefect must be Dai, according to the Self-Government Law of the Yunnan Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture. The Dai are still the largest minzu in the prefecture. Dai writing is visible everywhere—in public buildings, markets, bookstores, and other shops in towns, and on plates on private houses in villages. Most villages reached by road are Dai. In minzu middle school only Dai students wear ethnic clothes.15 If one did not observe carefully, one might think the Dai were the only indigenous people in Xishuangbanna, due to the fact that transportation to hill tribal communities is not convenient, so most tribal people neither come to town often nor are willing to wear their traditional costumes in public, especially the younger generation.

On a deep psychological level the Han in Xishuangbanna probably feel somewhat pressured or even threatened by the supposedly minority but actually majority Dai people. This is suggested by the fact that many Han in Xishuangbanna complained to me about everything concerning the Dai, and by the government’s praise of the hill tribes (such as the Jinuo and the Hani) as “minzu who have leapt across evolutionary stages” (kua shiji de minzu)16 because they encourage their children to get more education. Moreover, the chairman of the People’s Congress in Xishuangbanna is a Jinuo. Some Dai informants felt that the above phenomena showed that the government was deliberately attempting to restrain the Dai and extol other minzu. Nevertheless, both the Han and the Dai, according to my investigation in Jinghong, consider the Jinuo and Hani to be the most backward minzu, a status of which the Hani and Jinuo are well aware. The strong Jinuo and Hani support of government policy may well reflect both an effort to deal with their problem of stigmatized identity, and anti-Dai sentiments.17 In Xishuangbanna the only non-Dai civilization that the hill tribes can contact is Han. It is not surprising to see Jinuo and Hani who are eager to learn Chinese, to study in schools, and to acquire so-called advanced scientific knowledge—all symbols of high culture—in order to adjust themselves to the environment of Dai supremacy. Traditionally, the Tai were the superior people in the political, economic, and social dimensions of Sipsong Panna. At present, though the political power of the Dai no longer exists formally, in reality the design and arrangement of administrative autonomy in official appointments still indicates that the preeminence of the Dai is recognized by the Chinese government. Even though the Han criticize the “laziness” and “backwardness” of the Dai, and it is rumored that the government purposely restrains the Dai, many former Tai aristocrats hold appointments as vice-chairperson or prefect—in effect people of high rank have been transferred to another high level. The tribal people who are assigned official positions are insignificant to the Dai. One of my informants said, “Such an aka [slave] can be a vice-prefect—what a joke!”18 Another stated, “The chairman of the People’s Congress in Xishuangbanna is a Jinuozu. He is very bad—I hope he dies immediately.”

After the kingdoms of Lan Na, Keng Tung, and Lan Zhang were disconnected from Sipsong Panna one by one, Lue-ness lost its critical position in the ethnic identification of the Dai-Lue in Xishuangbanna. The Dai-Lue no longer need to show their Lue identity in the interactive network of Tai-speaking groups in northern Southeast Asia, since those peoples who equated Lue with Sipsong Panna Tai have withdrawn from the original northern Tai-speaking ethnic network. When the Dai in Xishuangbanna face the hill tribal peoples, they need to emphasize their Dai identity, since Dai-ness is the traditional emblem of superiority in the ethnic context of the area.

CONCLUSION

In the twentieth century, the Sipsong Panna Dai began to be affected by the changing interstate political environment. Members of the northern Tai “tacit alliance” were absorbed into various independent modern nation-states. The relatively isolated kingdom of Sipsong Panna immediately faced strong pressure from direct rule by the Han and from the constitution of the “Chinese minzu.” Chinese nationalism was constructed and developed in the first half of the twentieth century in response to continuous setbacks in contacts with the Western powers and industrialized Japan. Chinese intellectuals and politicians felt that emulating the Western model of the nation-state was the best way to overcome China’s weakness. The Tai leaders at that critical moment did not observe clearly the unusual situation in international affairs and in China’s politics. According to proponents of Chinese nationalism, because all residents of China originated from the same ancestor, everyone became a member of the “Chinese minzu.” Assimilationism was thus at that time the preferred philosophy among politicians and intellectuals. It was not so easy for the Dai to get along with the new China; they could no longer refer to themselves as “we stupid Baiyi” in their official petitions toward the occupying Chinese army in hopes that the troops would be withdrawn and that Han officials would not be sent to govern Sipsong Panna.

Originally, the Han strictly distinguished between Han and yi (barbarians). From the time when Chinese nationalism was formed, Chinese came to believe that yi (Baiyi and others) and Han belonged to the same family. All territories around the border, populated by yi but not occupied by Western powers, thus became the areas that Chinese were eager to dominate. At the same time an idea of an “indivisible mother country” was forming. The Han still called the Dai “Baiyi,” but, from that time on, the Baiyi were a member of the “Chinese minzu”—they were a kind of Chinese. The Chinese people and government could not tolerate the existence of an independent polity such as the kingdom of Sipsong Panna within China’s territory. Baiyi could survive, but the state ruled by the Baiyi should not be allowed to exist.

The political crisis of the Tai kingdom brought on a serious crisis of ethnic identity for the Tai, because of their homogeneous polity and ethnic identity. Instead of seeking a position in which they could survive politically in the new international circumstances, the Dai isolated themselves in an effort to cope only with the Chinese ideological and territorial invasion. When the traditional social norms and ethnic order within Sipsong Panna had disintegrated after the Chinese invasion, many tribal peoples revolted against the Han in order to restore their original condition—to maintain Sipsong Panna as an ethnic-state. The Tai, the dominant people there, did not appear to be as impetuous as the hill tribes, owing to long experience in dealing with the Chinese state, and knew the unchallengeable power of China. In the traditional mode of Tai-Han political relations, the Tai had always supported what the Chinese state preferred in conducting bilateral affairs. Now in jeopardy of losing their ethnic-state, the Tai were still following, at the time of the struggle between the Nationalists and Communists, their accustomed practice of supporting either of those two powerful Chinese regimes. They thought this was the only way for the Tai state to survive, not realizing that their ability to decide their own ethnic-political fate had disappeared forever.

The Dai have become politically and ethnically passive. Chinese ideology and policy toward non-Han peoples appear to be directing the future of the Dai and perhaps influencing creation or selection of the symbolism for their ethnic identification. The Chinese government established the Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture in the same location as the Tai kingdom. They also created a new ethnonym. The old name, Baiyi, a term popularly given and then officially used by the Han, had been accepted by the Dai in order to preserve peaceful and safe relations with China. Several hundred years later, it was prohibited by the Chinese government, and the Dai were given the Chinese name Daizu—instead of only Dai, or Dairen (Dai people). The Dai immediately used Baiyi no more, never arguing with the Han about the matter of their ethnic name. Daizu, like Baiyi or even Lue, definitely refers to the Dai only; such names did not threaten the basic identity of the Dai.

In Communist China, Daizu is an unchangeable concept. Daizu, no matter where they live, to the Han are all the same. The Chinese government and academic circles put those identified as Daizu into one category, so that a universal Daizu culture has been created by Chinese official writers. This inclusive Daizu group, however, has been divided on the basis of original ethnic-political aspects into several administrative units. Xishuangbanna Daizu Autonomous Prefecture and Dehong Daizu and Jingpozu Autonomous Prefecture are two of the major units. Each prefecture, according to the Constitution, is allowed to formulate laws encouraging regional identity.

A common interest among various groups classified in the Daizu is obviously lacking, as are strategies and institutions for promoting mutual integration under China’s ethnic minority policy. Many Dai college students distinguish between the Dai from Xishuangbanna and those from Dehong by means of the abbreviated names Xidai and Dedai. Xidai seems to be a newly created symbol of primordial identity; it is like ancient Baiyi and modern Daizu in their own interpretation that only the Xishuangbanna Dai themselves can share it.

Although the chao class no longer exists in Xishuangbanna, and traditional political ethnicity provides no symbols to identify with any more, the Dai’s ethnic boundary is still well kept. The fact that the Xishuangbanna Dai form an individual administrative unit reflects their common historical origin. The only change—a major one—is that this Dai area is an ethnic autonomous prefecture governed by Chinese bureaucracy, and no longer an independent kingdom. The conceptualization of Xishuangbanna and Daizu, which has created the new symbol Xidai, prevents the Xishuangbanna Dai’s ethnic boundary from being blurred. A passive ethnic-political identification has now been formed, based on manipulation by the Han. The Dai have to indicate their ethnic background in the section entitled minzu on all official forms. A Daizu person will remain so permanently under the political theory of multinationalities.

During the period when ethnicity was being suppressed (i.e., from 1957 to 1976), claims of ethnic identity by non-Han peoples seem not to have been allowed, yet the Han were qualified to emphasize the ethnic backgrounds of others if needed. The Dai responded very quietly toward Chinese sensitivity about so-called local-nationality chauvinism (difang minzu zhuyi). Ironically, the government was always doing things to keep the Dai from losing Dai identity. An important government-mandated activity was criticism of traditional ethnic leaders who were counted as the worst exploiters. All chao were forced to realize their aristocratic status (since the decline of the Tai kingdom, the chao class did not exist any more), and Dai commoners were compelled to speak out against the chao. The two major traditional classes in Dai society were thus artificially emphasized by the Chinese government. Both the chao and the Dai peasants thus found no way to hide themselves in the atmosphere of opposition to local-nationality chauvinism. And the chao became a negative symbol for the Dai people. Originally, the Tai were Tai because they shared a universally respected chao phaendin; later the Daizu were Daizu because they shared a disgraced chao phaendin. The chao phaendin and the other chao meeng were still significant symbols for Dai ethnic identification, but their status had changed from positive to negative.

Class struggles manipulated by the Communist Party ended after the Cultural Revolution. The chao as a negative ethnic symbol was no longer pointed out or emphasized, and the Chinese government adopted another strategy to stabilize the position of the Daizu. First of all, traditional expressions of ethnicity—such as pagodas, temples, Buddhist images, monks, ethnic scripts, festivals, and other customs—began to be restored. Daizu and Xishuangbanna were restressed as two major emblems of the Xishuangbanna Dai as a distinct group. Further, most of the previous chao were appointed as either provincial or local officials. The former ethnic-state—with its territory, people, dominant ethnic group, and ethnic leaders intact—seems to be re-emerging. Ethnic boundaries and geographical (or perhaps even political) boundaries are operating once again. The maintenance of Dai ethnic identity is probably based on an essentially unchanged set of boundaries, along with fixed patterns of interaction between the populace and traditional ethnic leaders.

The Chinese government unintentionally helps the Dai keep their identity, even while it practices a covert strategy of making China into an imagined nation-state. The Communist Party imagines that a nation should act as a family, members of which obey one head (the Han), share the same blood (as descendants of the Yellow Emperor), use only one language (Chinese), and behave according to one set of norms (Han cultural ways). The Party automatically criticizes big-nationality (i.e., Han) chauvinism in order to rationalize the oppression of ethnicity of the non-Han people, and requests that all peoples identify with the “Chinese minzu,” yet the main symbols representing this inclusive minzu are taken from Han culture. The nature of sinicization is Hanification.

Nevertheless, because the mechanisms that maintain Dai identity are still strong, the ethnic boundary of the Xishuangbanna Dai is tenacious. The Dai always distinguish themselves clearly from the Han wherever they are in contact. The lack of motivation on the part of the Dai in Xishuangbanna to understand their own role in the framework of the “Chinese minzu” is similar to the attitude of the Lue toward the “Thai nation.” The Lue in Thailand have shown strong hostility to the Thai-Siamese. Their maintenance of Lue identity is based on an imagination of the previous kingdom (their homeland in Sipsong Panna) and of the living chao phaendin. An impression and remembrance of governing an ethnic-state, which was a major mechanism for traditional Dai ethnicity, appears to exist in the minds of the Lue.

Much unsystematic information about Taiguo/Meeng Thai/Thailand began to spread into Xishuangbanna when China’s door was opened in the late 1970s. Their tragic experience during the Cultural Revolution directed the Dai to seek release from psychological and spiritual pain by imagining Thailand as “a great and wealthy Buddhist country”—a fundamental transformation of the Dai opinion of Thais as “brutal Siamese.” The Dai thus imagine that they have a respectable and proud brother country called Thailand. There seems to be no similar sentiment among the Dai toward the Chinese. It is possible that conflict could arise if the Chinese government perceives its nation-state building and “Chinese minzu” creation to be a failure in comparison with the successful maintenance of a Dai boundary. The closer the Dai approach to Thailand under such circumstances, the more dangerous the possible reaction from the Chinese government becomes.

1. Both anthropologists and linguists agree to using “Tai” to refer to all peoples who speak the Tai language. “Thai,” on the other hand, is reserved for the majority of the Tai-speaking peoples in Thailand, or citizens of the kingdom of Thailand. In 1951 the Chinese government created “Dai” to name the Tai-speaking ethnic groups who were mostly called Baiyi by the Han. “Dai” is used here only in the context of Chinese manipulation and domination under the People’s Republic.

2. In 1939 Phibun Songkhram, a powerful general who controlled national politics, changed the name from Siam to Thailand.

3. Mitsuo Nakamura (1969) and Shigeharu Tanabe (1988) referred to Sipsong Panna, or Lue, as a “kingdom”. Their use of this term did not give rise to any noticeable interest in Western academic circles, even though the study of relations between the Dai-Lue and the Communist polity and economy is a proposed research priority in the newly founded Thai-Yunnan Project of Australian National University. At the same time, neither Nakamura nor Tanabe is concerned about the symbolism of Tai kingship as a mechanism of ethnicity, nor do they attempt to reconstruct a more detailed and integrated configuration of the kingdom of Sipsong Panna. All we know about Sipsong Panna is that it was an “illusory community,” a term borrowed from Marx by Tanabe, or an “illusory kingdom,” a term employed by anthropologists and historians with conservative interests.

4. Shigeharu Tanabe argues that “the power of the kingship [in Sipsong Panna] was largely restricted to the capital and adjacent moeng [meeng, ‘local principalities’]” and adds that “the instability of the kingship was also a prominent feature, as the perennial usurpations and succession disputes show” (1988:5). However, he fails to explain how the royal family could exist for more than seven hundred years if, as he suggests, it was plagued by both the weak centralization of the kingdom and “perennial usurpations and succession disputes” (ibid.:15). Here we should distinguish between the external and internal political operation of Sipsong Panna. The Tai-Lue kings indeed were weak when China and Burma, the two suzerain states of Sipsong Panna, used the small kingdom as an arena in which to compete with each other, and separately appointed two different kings (ibid.:5). In other words, to China and Burma, the kings of Sipsong Panna appeared to be as powerless as the people. All the Sipsong Panna Tai were required to call the commissioners from China and Burma da ren (my lord). In internal affairs, however, the king did have stable power. All the local princes or chiefs of meeng knew that the authority of the king was granted by the powerful emperor of China. The king not only controlled the area around the Jing Hung, the capital, but could suppress any revolt by having his messengers report to Simao, Puer, or Kunming, Yunnan. The army would be sent immediately. For the most part, however, the king was not seriously concerned about internal conflicts in the meeng.

5. For example, in 1765 the Burmese captured the king of Keng Tung, Chao Meeng Jung, but his son escaped to Lan Zhang first, and then hid himself in Meeng Jie, Sipsong Panna (Li Foyi 1984:97). In 1886 many northern Tai princes and headmen fled from the uncertain social order in their own territories to the capital of Sipsong Panna (Zhu Depu 1987:203). Chao Long Pha Sat, uncle of the last king, told me: “When Chao Hmoam Siang Meeng [the prince regent and father of the last king] and I fled to Keng Tung in the 1940s, we said to the ruler, ‘You should help us, because we aided your ancestors several times before, and found a place for them to live in Jing Hung when they came as refugees.’ ”

6. In Sipsong Panna and probably most Tai-speaking communities in northern Southeast Asia Han Chinese are called Haw or Hok.

7. The Tai-speaking people living in what is now known as Dehong Daizu and Jingpozu Autonomous Prefecture are called Chinese Shan because of the similarity of cultural and linguistic traits with Shan in northern Burma.

8. The only time a ruler of the Lue state attacked Chinese territory was in 1403. Chao Si Rda Gham, the ninth king, marched to Weiyuan (Jinggu) and captured its head and people. China immediately warned him. The king was afraid of Chinese punishment. Not only did he send Weiyuan’s people back to their hometown, he also dispatched envoys to apologize for the offense to the Chinese emperor (Li Foyi 1984). In 1386 Ming emperor Hongwu wrote to the eighth king of Meeng Lue, Chao Gham Meeng (father of Chao Si Rda Gham): “I will follow the order of heaven and dispatch strong troops to suppress the evil Lu Chuan” (China gave the title Lu Chuan xuanwei shi to the king of Kausambi) (cf. Huang Huikun et al. 1985:83–84). It seems that Chao Si Rda Gham attempted to expand his territory and, considering the case of Kausambi, was ambivalent. He could not but give up his desire. In addition, because his father, the twenty-eighth king, Chao Hmoam Thao, was removed from the position of Cheli xuanwei shi by China on account of incompetency, in 1773 the twenty-ninth king, Chao Nam Peng, on the advice of his son-in-law, took a group of his relatives and officials and left Sipsong Panna to reside in Meeng Yong (Burma). In 1775 Chao Nam Peng went back to Sipsong Panna, but the Yunnan governor captured him in Kunming. His descendants were not given the right to inherit the position of Cheli xuanwei shi (see Li Foyi 1947 and 1984). This unhappy series of events caused subsequent kings to become more circumspect when dealing with China.

9. When General Wang Quanbin established control over the whole of Sichuan in 965, he asked first Song emperor Zhao Kuangyin for permission to march into Yunnan to conquer the state of Dali. The emperor thought that Nanzhao’s continuous attack had caused the decline of the Tang dynasty. He thus took a jade axe to a point on the Dadu River (in southwestern Sichuan) and said, “The areas beyond here are not mine” (cf. Ruey 1972:344) During the Song dynasty, aside from a few times when they sent special envoys to the Song court, the regimes of Yunnan had almost no contact with China. Chinese scholars know this, but never cite it because it does not illustrate the morality of the socialist philosophy of China’s unification.

10. According to The History of the State of Lue, in 1570 the nineteenth king of Meeng Lue, Chao Yin Meeng, divided his kingdom into twelve panna (administrative units), each of which could contain one or several meeng. Since then, the term Sipsong (twelve) Panna has been used popularly used for the original Meeng Lue.

11. The Ming government set up ten junmin xuanwei shisi in the southwestern part of the territory.

12. In February 1430 Chao Si Rda Gham attacked Weiyuan Prefecture, captured the prefect and a number of other people, and returned to Meeng Lue. Yongle, the third Ming emperor, asked the provincial official of Yunnan to warn Chao Si Rda Gham to send the prisoners back and return the land; otherwise the Chinese army would attack Cheli. Chao Si Rda Gham immediately complied and sent envoys to submit horses in apology for the offense. The emperor forgave Chao Si Rda Gham (Zhang Tingyu 1739:chap. 315).

13. For the Han people, “Chinese culture” (Zhonghua wenhua) definitely means Han culture. Even in academic circles, the Han have never developed any motivation to distinguish Han culture from Chinese culture.

14. Harrell (this volume) makes the same point with regard to the Yi.

15. The government has set up one or more minzu middle schools in each autonomous area, admitting minority students by examination. All students are non-Han, but most teachers are Han. The curriculum is the same as that in ordinary schools (see Borchigud, this volume, on schools). Several students at Minzu Middle School of Xishuangbanna in Jinghong told me that only the Dai were willing to dress up in their ethnic costumes to celebrate the anniversary of the school. Students complained that their costumes were ugly, and that they were ashamed to wear them.

16. The Jinuo were originally categorized by the Communists as belonging to the first stage of human social development, that is, they were very “backward.” So it is especially admirable that the Jinuo are eager to send their children to learn modern scientific knowledge—they appear to be a minzu of high achievers.

17. In Taiwan the aborigines’ almost universal belief in Christianity (which is presumably more advanced than Chinese Confucianism or Buddhism), can be seen as a means of releasing long-term anxiety about Han domination and of coping with the impact of the Han civilization (see Hsieh Shih-chung 1987). Similar cases are found in the relationship of the Kachin of northeastern Burma to Shan civilization (Leach 1954) and that of the Karen of the Burma-Thailand border areas to both Thai and Burmese civilizations (see Kunstadter 1979; Keyes 1977a), as well as in the relationships between Sani (Swain, this volume) or Miao (Cheung, this volume) and missionaries.

18. There are five vice-prefects in the Xishuangbanna Dai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture: two are Dai, one is Hani (Aka), and two are Han.